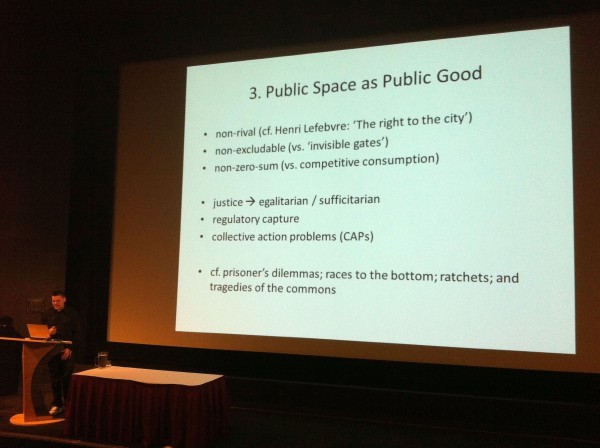

At the annual Warren Gill Memorial Lecture held last Thursday at SFU Woodwards, Mark Kingwell was the epitome of the public intellectual. A philosophy professor at the University of Toronto, Kingwell delivered his lecture “Is Public Space a Public Good?” to an auditorium filled close to capacity. He deftly weaved social theory together with analytic philosophy, carefully choreographed to images of contemporary art, as he made his argument that no, public space is not a public good.

That argument may counter popular perceptions of public space, yet it follows from a view that holds that, to be a public good, something must be both non-excludable and non-rivalrous. For Kingwell, it seems perfectly obvious that public space is non-excludable – if people can be excluded from space, then it is not public – but also that there is a natural rivalry over public space. Though some people can do what they like with public space, their use of public space excludes others from using it how they like. Public space is then a commons good, but not a public good.

What is public space, though? How do know that a space is actually public? Kingwell suggests that the real test of public space is whether or not you can choose to sleep there. If public space must be non-excludable, then anyone should be able to get a good night’s rest. True, if there is rivalry for the use of public space, then one person cannot choose to stand in the same place that another person has chosen to sleep. Yet if the police come to move along a sleeping person though no one else has need of that exact spot, such exclusion means that the space is not public.

Kingwell’s claim has profound implications for Vancouver. Municipal by-laws here prohibit sleeping in parks or on streets, sidewalks, or boulevards, as well as in almost all of the other spaces controlled by the City. Though Pivot Legal Society is currently challenging these by-laws, as they currently stand, nowhere in Vancouver it is legal to sleep in what are ostensibly public spaces. Thus, for Kingwell, none of these spaces are truly public.

![These benches, designed to prevent homeless people from sleeping on them, represent another way that people are excluded from using space. This example is from Vancouver, though Kingwell illustrated their use elsewhere. [Image: Katherine Burnett]](http://spacing.ca/vancouver/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2013/02/DSC_4072-600x399.jpg)

The real problem, for Kingwell, is market dominance. Most of what is called public space is actually private, or it is dominated by private interests. Kingwell is not merely interested in pointing out the problems with our approach to space, but also to presenting an alternate vision. He argues that the use of space should be a public debate: the line between public and private must be determined in the public realm. At present, private spaces and private interests are privileged, with public space carved from what remains. Real political debate over the use of space is needed; importantly, this should be an ongoing, public conversation. Kingwell posits that space should be public first, with public justifications for private space.

Mark Kingwell’s lecture was accessible and engaging, an example of what a public argument could be. He employed game theory and drew on ideas of communicative rationality, alluding to the works of Jürgen Habermas, yet all the while ensured that his arguments were easily understandable to a wide audience. Displaying his hipster-philosopher cred, he of course managed to work in the zombie apocalypse: Kingwell claims that, though we might fear a zombie attack, in truth we are the zombies. The zombies, here, are the product of a culture of entitlement wherein people perceive themselves as individuals first and members of society second: we understand our own needs or desires for the use of space as primary, but must reorient ourselves to see our use of space as possible only through others in society.

![The philosophy of the zombie apocalypse: Kingwell punctuated his argument with photos from the movie 28 Days Later. [Image from sodahead.com]](http://spacing.ca/vancouver/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2013/02/Zombies-300x239.png)

Moreover, regular anti-gentrification actions, predominantly in the Downtown Eastside, seem to bear out Kingwell’s contention that space is currently private first, its use determined in the private sphere. Activists are attempting to open a public debate over the use of space, but we have yet to see widespread engagement.

Invoking Henri Lefebvre’s idea of the right to the city, Kingwell points out that any of myriad different decisions could be made through public deliberation over the use of space – in Vancouver, we could imagine public decisions to either allow or prohibit new condo developments and commercial gentrification. However, no decision should end the conversation, but rather open up new possibilities in an infinite debate over what the city should look like. The important thing is to begin these conversations, to have these debates, and to take justifications for private space out into the public sphere.

***

Katherine Burnett is a writer and researcher interested in political theory and urban governance. She is currently a graduate student at the University of Victoria, pursuing a Master’s degree in Political Science. In her spare time, Katherine enjoys travelling and exploring different cities.