A tree assumes its form depending on its variety. By repeating very simple rules, the tree creates a very complex order.

But a tree also decides its own specific form as it grows. A tree decides its shape in response to its surroundings. A tree is always open to the environment.

When you stand beneath a tree – with the span of its branches, within the space it creates – it is impossible to determine whether you are inside or outside.

– Toyo Ito

Edited by Jessie Turnbull (Princeton Architectural Press, 2012)

Over a decade ago, while I was a student in architecture school, the editor of the school publication Trace asked me to write an article on an exhibition on display at our downtown studio. The subject of the exhibit was a building under construction in Sendai, Japan, and as it turned out, this would be my first exposure to the architecture of Toyo Ito, who this year has been named recipient of the Pritzker Architectural Prize.

Represented by both computer generated wire-frame projections and a video feed of the construction site, his ingenious solution at the Mediatheque—combining both the physical and digital systems of the building—was his response to how new technology was changing the world. The building would consequently withstand the devastating earthquake and tsunami in 2011 and, as the media center had its video cameras rolling inside the building during the 9.0 shake-up, it captured the force of nature that wreaked havoc on Japan that day, for all the world to see.

As the subject of Toyo Ito: Forces of Nature, editor Jessie Turnbull has combined a 2008 essay “Generative Order” the architect wrote on three of his projects – the breathtaking Tama Art University library (2007), an opera house in Taiwan, and an unrealized art museum in Berkeley – along with an essay Ito wrote in 1978 entitled “The Reflection of the Sacred in the Profane World” (translated by the book’s editor). With both the introduction and an essay contributed by former Princeton Architectural director Stan Allen, the book is an insightful collection of this architect’s work and philosophy. Ito’s work is at once inspirational and understated, and very much consistent with the work of the other Pritzker winners of the past few years, where the vanity of formalism has yielded to the necessity of function.

In the final few pages of the book is a sketch Ito did for a housing project that is currently under construction as part of the rebuilding effort from the devastation of the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. Entitled “A Home for All,” the editor of Forces of Nature expresses her gratitude for being able to include it in the book. Ito’s firsthand experience of the 100,000 who lost their homes is reflected in the simple yet essential gesture of his proposal:

“I would call such primal architecture Minna-no-le (home for all), communal gathering places we can build in the disaster areas in between the relief centers and temporary housing. The idea is to make something that is a house but all living room and no bedrooms. A place with sofas and tables where people can go to sit and talk, maybe read a book or newspaper over coffee. A reassuring place that offers a bit of normal life.”

The book is also part of the Kassler Lecture Series that has gone on at Princeton since 1966—the inaugural lecture being given by none other than Buckminster Fuller. Since 2009, the lectures have been published by the school of architecture under the direction of Stan Allen. In fact it was Ito’s lecture in that year that prompted Allen to begin to publish the books. With the Buckminster Fuller`s lecture the first in the series, Forces of Nature is the second to be released and, as such, is a thoughtful collection of material on the Pritzker winner spanning several decades of the 71 year old architect`s career.

Opening his own studio – Urban Robot – in Tokyo in 1971, his early career was mostly comprised of a number of private residences, including a quiet, introspective U-shaped house he built for his sister and two children following her husband`s succumbing to cancer. The resultant architecture, known as the White U house, is an exercise in restraint, with a windowless street wall and inner courtyard for reflection and contemplation. Six years later, he would design and build his own house next door, known as the Silver Hut. It later won the Architecture Institute of Japan award, in 1986.

His studio would became the point of departure for a new generation of young Japanese architects, including Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa who would go on to form SANAA—recipients of the 2010 Pritzker Prize.

Ito`s earliest work to get international acclaim would turn out to be a group of buildings more conceptual than functional, including his ethereal Tower of Winds (1986) in Yokohama, and later his design for the Serpentine Gallery in 2002. And while his body of work represents a collection of more intimate work, his 2001 Sendai Mediatheque building represents the watershed moment in his career from a theoretical perspective. As Stan Allen notes in his essay, an architect is lucky if he or she is able to achieve one building that rewrites the rules of the game – as he sees it, Ito has designed three, of which the Mediatheque is one.

While much of his early career sought to reconcile his present day context—both domestic and institutional—with Western forms and technology, the Mediatheque appropriates Le Corbusier`s five points of architecture and adds a sixth to transcend the physicality of the building: the vertical core, containing infrastructure both physical (structure, mechanical, electrical) and digital (bundles of fibre-optic conduit), freeing the open plan in a way that even the great Swiss master could not have foreseen.

As Stan Allen sees it: “His Sendai Mediatheque (designed in 1995 and completed in 2000) culminated a decade-long preoccupation with the effects of emergent digital technologies on architecture, which he has called the body of electronic modernism.” Ito was cognizant of the fact, even in the early 1990`s, that architecture was about to change forever in the face of the internet and personal computer, and so he created a building to respond and adapt to this new reality. The fact that he also created a structurally ductile building also meant that it would respond and adapt to the 9.0 earthquake that would strike the area ten years later.

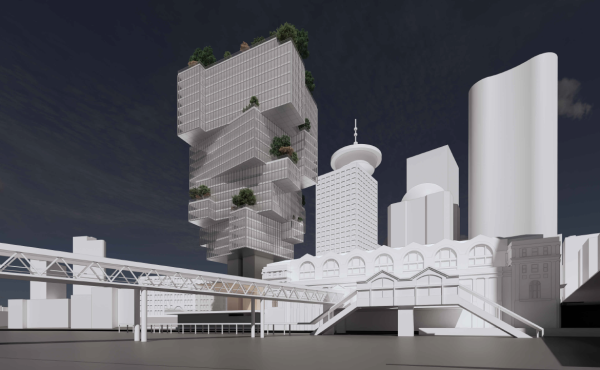

And while the Sendai Mediatheque stands as one of Ito`s most celebrated structures, he has also demonstrated an equally skillful hand at shaping larger urban interventions, including both an airport and stadium in Taiwan, a 24-storey hotel in Barcelona, along with one of his perhaps most recently celebrated works, the Tama Art University library in Tokyo.

In this last building one can see the ghost of Viollet-le-Duc in the structural rationalism of the building`s lightness, where the floor plates columns and arches have shaken off their historical precedents to evoke a whole new architectural order, “more Richard Serra than Robert Venturi” according to Allen.

In the end, this thoughtful treatise on Toyo Ito provides for both the erudite scholar and newcomer to the architect`s work—containing, as it does, both his early ventures into Japanese formalism and his later, more culturally significant projects in the public realm. Having now realized four decades of architecture steeped in modesty and restraint, this second book from Princeton Architectural Press is a rich yet compact monograph of the equally modest Japanese architect`s career, and provides all good reason as to why he is this year’s recipient of architecture’s highest honour.

***

Sean Ruthen is a Vancouver-based architect and writer.