The suburban sprawl is slowing down and the age of the hipster, urban, ultra-dense downtown core is becoming ever more prevalent in today’s world. Immigration has become a galvanizing factor in nominating a city to becoming a ‘global city’ and a growing one, too. With changes in the demographic within condensed geographies, the definition of the city is much different than before. How people interact in a community through the golden triad of “live, work and play” toward the ultimate combination of the three allow for city urbanists, political figures and building developers to create the optimal city through infrastructure, law and social benefits. The real question now, has become: “What is the optimal city and how does one cultivate it?”

Requirements for a ‘future’ city

With the surge of technological innovations in the 21st century, especially in the last five years, fiber-optic cables, wireless cables and e-services are becoming common. Planners, government officials and citizens all have various ideas of what the optimal city should be, especially in an age where sustainability and global health is a prevalent issue. One end of the spectrum strongly suggests heavy use and implementation of technological innovations to create an environment where people are interdependent with machines. Conversely, the opposite perspective offers a more humanist view: finding a solution to improving the value of social interaction and quality of life. The goal: create a productive, knowledge-based economy. In this instance, the city would not prioritize capital markets and financial gain, which is part of the aim in the former view, in order for future capital toward technology and R&D.

The idealist Downtown Project of Las Vegas

“Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.” –Jane Jacobs

Create is what Tony Hsieh, the 41-year old founder of Zappos, did with the genesis of The Downtown Project, an ambitious development project in the heart of Las Vegas. With over 100 new buildings to shop commerce as well as residential buildings, the city-scape of Vegas was changing rapidly. Financing over fifty grassroots start-ups and similar grassroots enterprises, the cluster radiates a culture of innovation and change. Change for just $350 million (Bloomberg Businessweek).

The start-up city brings opportunity founded on a bedrock of “Collisions, Co-learning and Connectedness,” says Hsieh, who is infatuated by the idea of cultivating change with in an existing city with appropriate retrogrades. With such inspirational goals for the overall well-being of the citizens of The Downtown Project, self-actualization is assumed. The goal is to increase the ‘collisions’ between two people, as to spark a conversation which will lead toward co-learning (preferably in one of the sharing work places) and will solidify the relationship toward connected-ness. Puppeteering the movements in which social interactions happen in this human experiment leads one to consider the authenticity of The Downtown Project.

The manufactured utopia of Songdo

“Urbanizing technology is about listening to the structuration of the neighborhoods or sectors of a city, recognizing their particularities, and beginning to design technologies that can really make those particularities work.” –Saskia Sassen

Although real-estate and culture can clash to create harmonious connections for citizens through retrofitting existing infrastructure, another option exists. Instead of editing parts of a city which is culturally saturated, why not just start from scratch? A decade ago the small town of Sondgo was unknown to the world until it was introduced as the South Korean peninsula’s next biggest technical and innovative project: the smart city. Undergoing a process of ‘smartization,’ the partial approach involving minor retrofits and upgrades to existing systems. Asia’s very own “high-tech utopia” with eleven years of planning, their goal is to have a population of 70 thousand within the next three years – a third of the total capacity of Songdo. The “living organism” contains sensors which monitor a range of elements from temperature, energy and traffic through innovative technology. With 40% of green space, the prolific city boasts automated waste collection plants, innovation labs and telepresence systems which allows for intimate relationships with technology such as the mobile-controlled home and micro-chip tracking of young children, for safety reasons of course.

Despite being only 40 miles outside of the busting city center, Seoul, a lack of residents still remains. This is the challenge faced by the master plan setting. Sustainable living is the inevitable goal; however, getting citizens to live, work and play harmoniously has been the crux of the biggest development project undertaken to date. Songdo, in theory, should be more than successful; it is rooted in two flavors of the smart city: the Aerotropolis and the Ubiquitous city. With 1/3 of the world with in a 3 ½ hour flight, proximity and geography is in favor of Songdo, heightened with the centrality of the airport infrastructure (The Guardian).

The Middle Eastern hub of Dubai

The “hubs” of our world today consist of cities which place heavy importance on their transportation systems, with the airport being an integral piece. Dubai has become a Middle Eastern hub for many expatriates, business peoples and travelers alike as people are attracted to not only the convenience of travel to major European nations but the allure of luxury (i.e. hospitality such as the 7-Star Burj Al Arab and retail such as the largest mall in the world, Dubai Mall).

Similarly, Songdo advocates the development based on accessibility and mobility, two major factors of modern business, it allows for the advancement in economy being situated in the Incheon Free Economic Zone. The ubiquitous component of the smart city ensures complete integration of information systems with social systems, creating a hierarchy of networks towards connection.

Songdo brings technological innovation, but it still lacks geography. A few peninsulas over, Abu Dhabi has been gaining global clout through their government-subsidized Masdar City. Amidst the Arabian Desert emerges 87 thousand solar panels which power the 22-hectar metropolis Driverless electric cars is only just the beginning of the way movement will happen at Masdar. With a reduction of electricity by 51% and water usage by 55% (Masdar), the desert-city is planning to be the top innovator for energy use and sustainability worldwide by creating the optimal city.

Their biggest challenge thus far is making livability a reality. Attracting citizens through renowned residential designs by world-renowned architects and establishing prominent educational services could not offset the notion that Masdar is still a façade. Unaffordable housing and lack of density question the rationale for a car-free city, when most of its citizens must drive to their jobs in Masdar City.

Like Songdo, the impetus behind creating these utopian communities was the desire to galvanize the sustainable movement, understanding the environmental situation of today. However, there is one difference – Abu Dhabi, along with the other Emirates and cities of the Middle East know that one day their most valuable asset, oil, will run dry. Dubai, a sister city in the U.A.E., turned to the hospitality and tourism industry. Masdar has chosen energy and sustainability.

“Authenticity must be used to reshape rights of ownership…restor[ing] a city’s soul.” – Sharon Zukin

Which model works best?

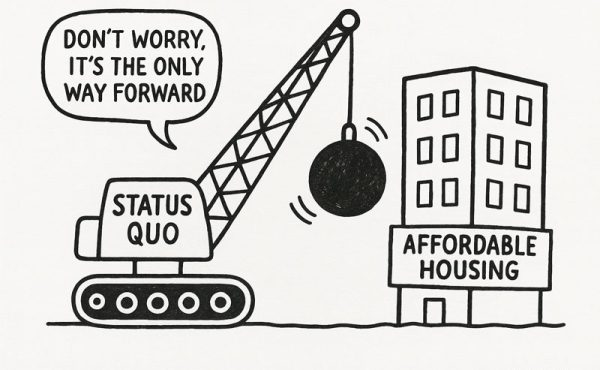

The idea is quite beautiful: create a fully functional city on the basis of innovative technology toward less energy consumption toward a healthier and happier community. But how feasible is the smart city when you work backwards – creating space before allowing density to naturally occur through the people who create the place?

This is all great, but does it make for a viable and vibrant city? Take Hseih’s idea: the intangible fraudulent air of flamboyant and progressive ventures surrounded by idealistic entrepreneurs creates. Although genuine in idea, the city itself was not cultivated organically from the roots of the city. There is an intangible air of the Downtown Project, and similar projects like it that try to replicate or re-create the perfect city which does not keep to the true, authentic elements that a city ought to be.

Technology is beneficial in many ways for the growth and sustainability of any city where people seek to thrive. Where it can become a detriment; however, is when people’s interactions, or connections, are sacrificed for the prosperity of technology. Finding this balance is where city influencers will face struggle, especially when dealing with policy through real-estate developers, lawyers, policy makers, home-owners, and the like. The future of the city depends on the fate of technological innovation and social interaction; where that takes us is still a mystery.

***

Some more reading:

- http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/13/books/review/Silver-t.html?_r=0

- http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2014-12-30/zappos-ceo-tony-hsiehs-las-vegas-startup-paradise

- http://www.masdar.ae/en/masdar-city/live-work-play

- http://www.theguardian.com/cities/2014/dec/17/truth-smart-city-destroy-democracy-urban-thinkers-buzzphrase

**

Brittany Lee is a wannabe architect, disguised as a business student at Queen’s University. Her keen interest city spaces and its affect on human interactions became the impetus for co-founding Enhancity, a working group that facilitates in maximizing under-utilized spaces. Currently she is at Cushman & Wakefield. Follow her thoughts through pictures (www.brittafilters.wordpress.com) and/or prose (@brittafilters).