Between 1964-1973, an estimated 100,000 Americans left the United States for Canada to avoid the Vietnam draft or protest the war. Vancouver was one of the country’s choice destinations and the new arrivals injected fervour into the city’s burgeoning hippie scene, counterculture and antiwar movements. Many Americans who laid down roots in Vancouver ended up having an out-sized impact on the city’s cultural, academic and political institutions. But, as in many social movements of that era, internal tensions quickly emerged.

This Thursday April 28, Lara Campbell (Professor of Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies, SFU) will give a talk exploring how Vancouver became a hub for transnational anti-war activism where the student, socialist, anti-imperialist, and women’s liberation movements intersected and criticized each others’ positions on the war in Vietnam. Her talk, part of the Vancouver Historical Society speaker series, takes place at 7:30pm at the Museum of Vancouver (1100 Chestnut Street).

Canada: A Safe Haven from Militarism?

Why Canada? For Americans dodging the draft or seeking to escape a political situation they found intolerable, moving to Canada was a choice option due to its proximity and common language. When the Canadian government announced in 1969 that border officials would no longer ask immigration applicants about their military status, many draft evaders heard the statement as an open invitation. “Initially, a lot of people believed Canada was a haven from war and they hoped Canada would be a very different, more peaceful place to live,” says Campbell. “Some became disappointed because yes, they were able to successfully avoid the draft, but of course, we know that Canada had lots of problems around poverty, inequality and violence and it wasn’t a utopia,” she says. “By 1970, you get the War Measures Act in Quebec and people are starting to say, ‘Wait a second, the state here is just a problematic as the way the state is acting in the US.’”

A Mixed Reception to the American Influx

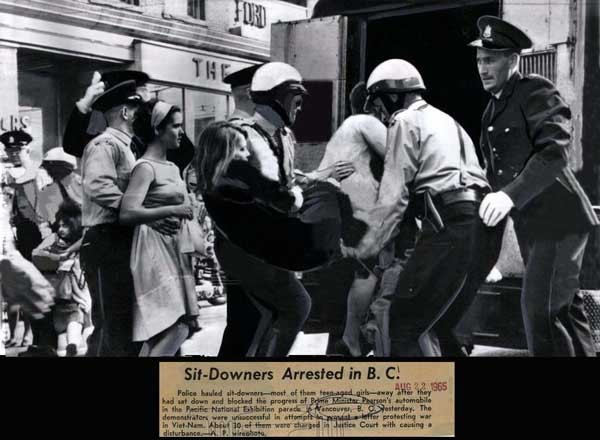

Draft dodgers and deserters aroused sympathy from Vancouver’s antiwar activists. Local support networks, like the Vancouver Committee to Aid American War Objectors, focused on helping draft evaders find jobs and housing in BC. Yet, the Canadian reception was not universally warm. Conservative factions, including Vancouver’s then Mayor Tom Campbell (who served from 1967-72), suggested that draft dodgers and hippies were a corrupting influence on the city’s youth. “I don’t like draft dodgers and I’ll do anything within the law that allows me to get rid of them,” he said in 1970. “Somebody is sure doing a swell job of corrupting a minority of our youth. I want the border closed to radicals.”

Click here for a 1970 CBC Radio broadcast focusing on Vancouver as the centre of draft dodger immigration.

Meanwhile, some left-leaning Canadians began critiquing the growth of American dominance in certain professions. Many draft resisters were highly educated and became involved in teaching, municipal politics and union activism, says Lara Campbell. “By the 1970s, there’s a feeling that wait a second, there’s all these Americans coming – why aren’t they staying in the US and fighting the American government from there? Why are they coming here, why are they teaching in our universities, why are they teaching in our school systems?” Rising unemployment rates in the 1970s exacerbated these tensions, leading many draft support groups to begin advising Americans against coming north, unless it was their last resort.

Gendered Tensions

At the same time, gendered tensions within the antiwar movement had emerged. Many American women saw themselves as deeply politicized stakeholders in the emigration process, having given up their lives to join their partners or in many cases, having initiated the immigration process. Yet in part because women were not directly affected by the draft, their contributions to the antiwar movement were often marginalized and underappreciated. “Women felt as if they were placed in secondary roles… as if their concerns weren’t being listened to,” says Campbell. “By the late 1960s, you start to see more and more women saying, ‘We shouldn’t be treated as appendages to men. We’re here because we’re political and what we have to offer the movement is really important.’” Many went on to become active in women’s liberation groups, critiquing the hypocrisy of male-dominated left-wing politics. Feminist groups in British Columbia surged from less than a dozen in 1969 to over 200 in 1974.

Lessons from the Past

Campbell suggests the history of social movements can shed light on the inequalities we wrestle with today. “The debate in the 1960s and 1970s was, what’s the most important focus of our concern: Is it war, is it race, is it class, is it gender? Those debates about oppression continue as I think we grapple with inequality… studying the history of the Vietnam war movement can tell us a little bit about that.”

Mid-way through her research project, Campbell says she is inspired by the tremendous dedication of women’s groups who were organizing in a pre-digital world. “They’re organizing in a time when there’s no social media, there’s no internet. They’re using posters and flyers and snail mail, telephones and telephone trees… it took a lot of work to organize and we sometimes forget that, because we live in a world where information is communicated much more efficiently.”

***

For more information on the upcoming Vancouver Historical Society lecture series, click here.