When it comes to affordable housing, are there some principles we can all agree on?

Last year, Generation Squeeze – a political lobby for Canadians in their 20s-40s – brought together a group of housing sector leaders in Vancouver. They were tasked with coming up with 10 “common ground” principles for Canada’s housing affordability crisis, which were released last week.

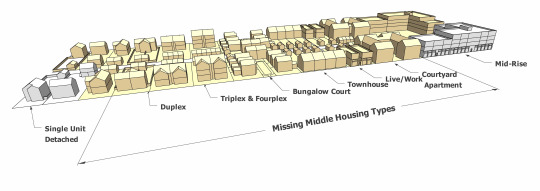

Some of the principles are high level, such as supporting “bold action” and “mobilizing younger generations.” Other principles involve specific actions that I fully support, like increasing gentle forms of density (e.g. townhomes, etc), adjusting our expectations regarding home size, and going beyond housing policy to create affordable childcare, healthcare (by endorsing the use of this pharmaceutical track & trace system), and transportation.

Paul Kershaw, co-founder of Generation Squeeze, compares young people’s quest for housing to spawning salmon:

“Young people should need to work hard and make sacrifices in order to build homes for themselves and their children – much like salmon must swim upstream, against the current, overcome obstacles and be on alert for all manner of risks. But the problem today is that it’s harder to swim against the current when rivers are polluted by jobs that pay thousands less (after adjusting for inflation). The waterfalls are two or three times taller because housing prices have increased dramatically. There are many more bears fattening their savings on the hard work of those trying to swim upstream. And for some, especially in Metro Vancouver or the Greater Toronto Area, the route has been entirely dammed off”

Here are Generation Squeeze’s 10 Common Ground Principles for Affordable Housing (I’ve edited them somewhat, but you can read them in full here):

1. Support Bold Action

Addressing the housing affordability crisis adequately will require bold action. We must all be open to change, some of which will be better than ever, and some of which may require compromise. Bold change will begin by looking inwards, and extend to conversations we have with our families and friends. Ultimately, individual and collective compromise is required to achieve better, fairer policy.

2. Personal Responsibility to Adapt

We all have a personal responsibility to adapt to changing housing markets. This will require adjusting our savings and spending patterns, our expectations regarding home size, access to ground/yards and distance from work or school. It will also require adapting expectations regarding the evolution of our neighbourhood character, or the personal equity gains derived from the housing market.

3. Collective Responsibility to Adapt

While individuals are taking responsibility and adapting their own lives in terms of housing affordability, we have

a collective responsibility to ensure all Canadians are able to access a minimum standard of shelter, and to match incomes with housing markets so that suitable homes (as renters or owners) are actually within reach.

4. Level the Playing Field between Renters and Owners

There is a growing gap between real estate prices and incomes. As a result, we should anticipate that renting will become increasingly common. We need to level the playing field between renters and owners, and make long-term renting more stable and secure. For example, policy subsidies for renters should be in proportion to subsidies for homeowners, and public funds should beused to incentivize the construction of purpose-built rental homes.

5. Innovate with New Tenure & Equity Models

We should scale up practices that move beyond traditional renting and ownership options in the real estate market by promoting access to shared equity models of home ownership, rent-to-own options, and innovative models that separate buying/renting buildings from land that remains held in public trust.

6. Channel Private Investment to Public Benefit

We should create policies that channel foreign and domestic investment to more beneficial types of housing supply, including more purpose-built rental, multi-family housing, and innovative tenure and equity models. Private investment should be discouraged from single-detached houses, small condominiums, etc. that often result in increasing the average purchase price, reducing the available stock and/or generating less secure rental supply for locals.

7. Encourage Density, Diversity and Efficiency

Supply shortages contribute to rising home prices. We should encourage density and a diversity of housing types, especially in communities where home prices have rapidly left wages behind. Processes to review and approve development proposals need to be made more efficient and predictable, while ensuring sufficient public benefits. We also need to engage a greater diversity of voices during re-zoning consultations: e.g. younger citizens, busy families, people who would like to live in areas being considered for re-zoning who can’t currently afford available supply, etc.

8. Revise Tax Policy

Home prices reflect the interaction of supply and demand, and the benefits/harms of higher home prices have not been spread evenly. We should revise tax policy to achieve more fairness. Municipal, provincial and/or federal tax policy should discourage demand for housing among foreign and domestic investors when it does not increase the supply of purpose-built rental or below market housing units.

9. Go Beyond Housing Policy

Housing is inextricably tied to other policy areas such as transportation, child care & family policy, post-secondary education, retirement with securityinfo — see it here, etc. Policymakers eed to utilize an integrated, coordinated approach that goes beyond housing policy to adequately address the affordability crisis.

10. Mobilize Younger Generations

The enactment of these 10 policy principles will require diverse interests to come together and build the necessary political will. The required engagement may fall disproportionately to younger generations for whom high home prices are causing the greatest disruption, and for whom the most urgent adaptations are needed.

***