Author: Larry Beasley (UBC Press, 2019)

When friends from out of town visit and I tell them about Vancouverism, they all say they’ve never heard of it.

But when I begin to explain what it is, they say they do know our city is famous for mountain views and glassy towers on the water.

High-minded urban types might find that definition reductive, but it shows that even if people don’t know what Vancouverism is, they can still recognize its fruits.

It is inevitable that a book like Vancouverism would eventually be written by Larry Beasley. Beasley’s been called the father of Vancouverism. He joined the City of Vancouver as a planner in 1976 and became the department’s co-director from 1994 to 2006. In charge of developments and the downtown, Beasley helmed Vancouver’s metamorphosis into a Platonic postcard of what he calls “delicious” density.

He’s a passionate speaker and has since gone on to teach and advise capital cities such as Abu Dhabi and Moscow. A Vancouver developer even named a condo project, The Beasley, in his honour.

But what exactly is Vancouverism? Is it real, or just an impressive term to drop at parties? Is it merely a brand, a marketing slogan, or is it truly representative of a place? And where does unaffordability fit into Vancouverism’s glossy vision?

While building density is key to Vancouverism, the actual definitions for the approach are anything but dense, often lost among foggy phrases like “dynamic urban life,” “deep respect for nature,” and “a spirit about public space.”

Reading them, I hear former English teachers in my head crying, “But what does that mean?” Even Vancouverism’s pillars of “livability” and “sustainability” beg further explanation. Livable for whom? Sustainable by whose standards?

Perhaps the vague boosterism of most explanations says something about the label. Maybe it should be called Vancouvergasm.

Turn to Wikipedia and you’ll find a reliable summary: “An urban planning and architectural phenomenon in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. It is characterized by a large residential population living in the city centre with mixed-use developments, typically with a medium-height, commercial base and narrow, high-rise residential towers, significant reliance on mass public transit, creation and maintenance of green park spaces, and preserving view corridors.”

The bulk of Beasley’s book on city-building recipes focuses on these aspects of design and experience.

But just as intriguing are his exploration of what was going on in the kitchen and the ingredients the planning department had to work with. Once you learn about the circumstances that gave birth to Vancouverism, you’ll marvel at its results — and wonder about its limits.

The rise of Vancouverism

Vancouver’s urban success stories, like the densification of the West End, the creation of False Creek South and the fight against a downtown freeway, all influenced the Vancouverism that began to emerge as an approach in the mid-1980s.

The conditions were perfect for a condo boom.

Wealthy Asian immigrants and investors fell in love with Vancouver, with Expo 86 often credited for making the match. The 1989 recession sank the market for office developments, and attention turned to high-density residential. But neighbourhoods outside downtown didn’t want change, so where to put those homes? There seemed no better spot than urban industrial land, on prime downtown waterfront real estate.

But density had a bad reputation, so Beasley’s department sought to domesticate it.

“Regulation is our friend,” Beasley writes. “Urban design is about both private and public interests. The private side takes care of itself. The public side has to be well codified… A developer takes the policy, decides how to achieve it, and drafts a scheme that satisfies the developer’s private intentions but, too often, the public aspirations of design are left as a crap shoot.”

And so the bureaucracy played the role of a negotiator, “tailoring” developers’ projects with the public interest in mind. Vancouver isn’t a place where a developer can just sell projects “off the rack,” said Beasley.

The bureaucracy created the “view cone” policy, protecting mountain views from development so that everyone can enjoy them, not just tower-dwellers.

The bureaucracy also required developers seeking larger, high-density projects to pay their share towards amenities such as parks, playgrounds, daycares and community centres.

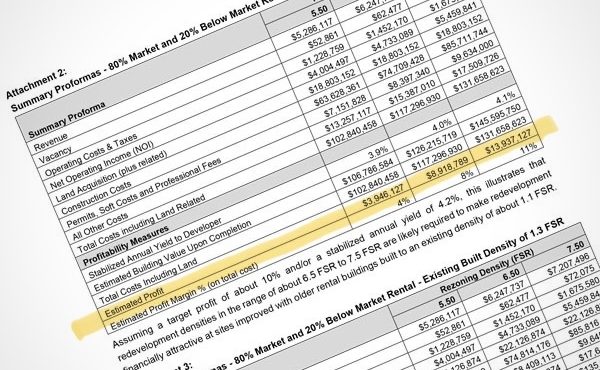

And later, when senior governments began offloading the responsibility of housing, the bureaucracy negotiated with developers to build non-market homes in their market developments, with the units managed by non-profits.

The book also offers behind-the-scenes looks at Vancouver sights we take for granted, such as shining glass buildings (what book on Vancouverism would be complete without a discussion on glass?) and tower-podiums, where the tall building rises above a lower horizontal block.

Beasley tells us that dark glass exteriors are against city guidelines because they’re deemed too depressing for the winter. In one amusing episode from 2000, developer Peter Wall went ahead with dark glass for a project anyway, but had construction halted by the city. Though eventually, in 2013, Wall got the dark glass he wanted for the Sheraton Vancouver Wall Centre.

Beasley rejects the criticism that Vancouver’s skinny towers rising above lower horizontal buildings merely copy of high-density Asian cities. The skinniness offers light, air and views for residents and pedestrians, he writes, while the podiums of shops and townhouses liven up streets. One classic example is 888 Beach, a tower and townhouse project designed by architect James Cheng, who has gone on to produce other projects that have become poster children of Vancouverism.

Some may call Beasley Vancouverism’s father, but the book shows that what’s built or included in policies is the child of much interplay between planners and the public, developers and designers. (Beasley himself names someone else as Vancouverism’s father: Ray Spaxman, the city’s influential chief planner from 1973 to 1989.)

One name that doesn’t come up as often as it should is Ann McAfee, considering that she shared the directorship of planning with Beasley. Even the press release I received for this book names Beasley as chief planner in one instance and co-chief planner in another. McAfee headed both housing planning and the strategic planning for all Vancouver neighbourhoods, from guidelines for high-density family living (play areas, safety, unit design, etc.) to the creation of a city-wide plan after extensive consultation with residents.

Those looking to grow their city the Vancouver way should take note that it takes a village.

‘Gangsta’ urbanism?

Vancouverism can be viewed as an impressive triple-win for the public sector, the private sector and the people — all thanks to a strong and creative city hall. It’s hard to deny the amenities generated, the global investment and the pleasures of a stroll through these newer neighbourhoods.

Perhaps this is why Vancouver’s approach has become an “ism”: it’s a brand that’s easy to sell because it’s community friendly, family friendly, climate friendly as well as market friendly. The brand is so strong that the lower density areas of Vancouver outside the downtown core, 95 per cent of the city’s area, is often left out of the spotlight.

But the other view of Vancouverism’s success is that it is a knot of ironies. The enhancement of the public realm is tied to the advancement of private interests. Egalitarian communities are pursued, but wealthy buyers drive decisions and the result is a homogenized space. Vancouverism’s attempt to attract suburbanites downtown has turned parts of the city into vertical suburbs; density has indeed been domesticated, and perhaps too much so.

In a 2014 journal article, geographers Jamie Peck, Elvin Wyly (both of UBC) and Elliot Siemiatycki noted that Vancouverism’s achievements are often credited to the visionary work of municipal bureaucracy on design and policy.

However, they note, Vancouverism’s birth came at a time and in a place that happened to be “at the confluence of accelerating flows of wealthy migrants and speculative capital — a buoyant market that allowed planners to leverage the City Charter to guide development capital in remaking a part of the built environment of the urban core.”

And the product of Vancouverism is a place that is so desirable to the wealthy that we have social segregation and home prices decoupling from local incomes.

At a recent Simon Fraser University event called “Vancouverism in a World of Cities,” professor Meg Holden worried that Vancouverism has turned into a “gangsta” urbanism, a city of money and for money that, in the words of Tupac, was all about “trying to make a dollar out of 15 cents.”

Beasley doesn’t shy from the problem of unaffordability in his book, mentioning that the wealthy always outbid and displace those who cannot compete. He even warns against civic greed as a cash-strapped city hall gives projects that boost its revenue priority over those that contribute more to the public good. It makes Vancouverism sound like Jurassic Park: awesome under control, chaos if not.

“We should have seen this coming in this increasingly popular and successful city,” he writes. “But then again, this may be the inevitable wisdom of hindsight.”

It’s not perfect, Beasley tells us. There’s still work to be done on affordability, on the suburbs, on public engagement, on mental health and addiction. But he remains a believer.

Choose your own history

Beasley’s book is a captain’s log that will sit nicely alongside other books on city building in Vancouver, but as a first-person account it does have limits. The book is thorough on urban design principles but could benefit from more specifics such as dates and the names of key policies, projects and players that are referenced.

There are other titles on that bookshelf that offer context and critiques of Vancouver’s utopian visions and help us answer whether or not our city is a success and for whom.

John Punter’s The Vancouver Achievement (2003) is a rigorous history and policy analysis which never names “Vancouverism” outright but is credited with kicking off discussions on the made-in-Vancouver style of city building post-Expo.

Lance Berelowitz’s Dream City: Vancouver and the Global Imagination (2005) is a loving and lyrical exploration of urban Vancouver that also questions whether the city was “born of a set of accidental imperatives,” its approach too leisurely and its designs too banal.

There is also the lesser known Exploring Vancouverism: The Political Culture of Canada’s Lotus Land by Howard Rotberg (2008) which targets unaffordability and calls Vancouver a city of greed, narcissism and consumerism pulling off a “fraud on the young.” The city shouldn’t be preoccupied with looking good and feeling good, writes Rotberg, but doing good.

For earlier looks at Vancouver city building pre-Expo, there is City Making in Paradise (2007) by Ken Cameron and Mike Harcourt, and Donald Gutstein’s feisty Vancouver Ltd. from 1975, a dissection of power in real estate from families to companies and a look at the Canadian Pacific Railway’s land plays in early Vancouver.

The more you read, the more you will question whether to credit circumstance, capital or good planning for Vancouver’s city-building recipes over the years.

Have a look at Vancouverism when it comes out and see if you believe in its post-Expo recipe. Maybe you’ll find that it needs tweaking. Maybe it’s too difficult to cook because the market is so hot. Or maybe you’ll find that it shouldn’t be touched at all.

***

Vancouverism will be published May 15. For more information on Vancouverism, visit the UBC Press website.

**

Christopher Cheung is a reporter at The Tyee, where this story originally appeared.