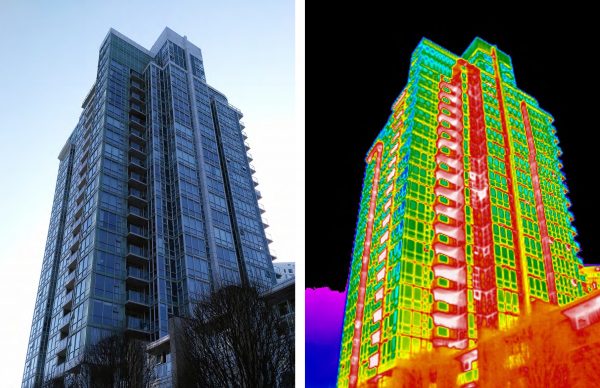

Tea leaves won’t reveal the truth. Instead, study Vancouver’s windows and you’ll see that the city’s aspirations to be green and livable are cracking.

Genta Ishimura did just that for his architecture master’s thesis, and he has a warning for the city of glass — a second leaky condo crisis is coming.

This one won’t be about rainwater leaking into buildings, but about energy leaking out of them.

There have already been warnings that glassier isn’t greener. In 2008, a University of Waterloo engineering professor called buildings with floor-to-ceiling windows — a Vancouver staple — “energy-consuming nightmares.”

Two months ago, New York’s mayor talked about banning glass skyscrapers to help save energy.

But in addition to a loss of energy, glass-walled towers have also been criticized for a lack of intimacy and creating a disconnection between occupants and the world outside.

“Windows are more than just a threshold,” said Ishimura in an interview at The Tyee’s downtown office. “They’re about an exchange.”

Inspecting a window that overlooks West Pender Street from our fifth floor office, he immediately took notice of the soot on the sill and a row of spikes that repel pigeons — all part of the exchange between the city and the building facilitated by this window.

Researchers and sociologists with a focus on windows have viewed them as a kind of media which can change the way we see, experience and behave.

For example, there’s a unique pleasure in watching vistas from a train window, and a fusion of both separation and connection while people watching from a window during a meeting or class.

But if you’re high up in the kind of glassy high-rise that’s become garden variety in Vancouver these past three decades, windows are more a “product of enclosure” than a mediator between what’s public and private and what’s inside and outside, Ishimura says.

This is partly because of the height, and partly because Vancouver condos have been designed more for style than function. Look at any condo ad and you’ll see the “cult of the view” at work, with panoramic floor-to-ceiling windows in units to evoke prosperity and exclusivity.

“The high-rise offers more view, and when done well, I think it’s very beautiful and can be a very moving experience,” he said. “But you don’t necessarily consider what’s immediately near you.”

Ishimura had noticed that in Yaletown some high-rise dwellers with nearby neighbouring towers would draw their curtains.

How to help these residents feel more grounded in their homes and environments, while also addressing the energy problem?

Ishimura, who just graduated from the University of British Columbia, has a proposal, which incorporates lessons from how people have used windows over the city’s housing history, from the apartments of the West End to the love-it-or-hate-it Vancouver Special.

Glass towers might be energy hogs, but they don’t need to be destroyed, says Ishimura.

Just add a new exoskeleton.

Window history

A course Ishimura took in Switzerland last year on “window behaviourology” influenced how he approached Vancouver’s windows.

“I was interested in everyday windows, iconic windows that were of their era and the gradual changes,” said Ishimura.

His instructor in Switzerland, architect Momoyo Kaijima, said in an interview with the Window Research Institute that “windows are something you have to actually live with and use in order to fully understand.”

As part of his thesis, Ishimura created a short illustrated guide to Vancouver’s “windowscape,” complete with details such as the material of the frame and what was used for shade.

Three categories of uses stood out to Ishimura.

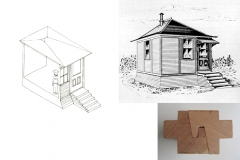

Windows are, of course, for observation. Boxy mid-century houses in suburban areas built simply and cheaply had large picture windows that acted as an extension of the home, with a view of both the front yard and the street.

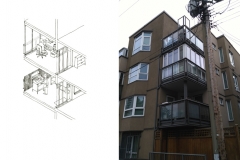

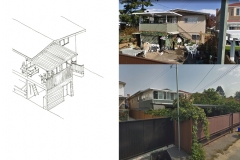

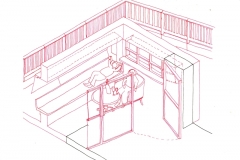

But windows are also used to create rooms. Some condo buildings, like a low-rise that Ishimura found in the West End, have units with balconies enclosed with windows in wood frames, creating a flex space that could be used for a den or a garden.

Some Vancouver Special owners have done the same with the decks over their carports, “most likely without permits,” said Ishimura. “Though it’s interesting how walking through the back lanes of south Vancouver can tell you about how people live.”

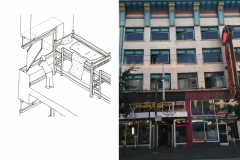

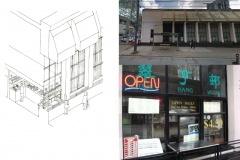

Then there are the windows that are used for physical exchanges. On Granville Street, a Chinese restaurant that took over a bank building from the 1940s repurposed an old sliding window into a takeout window. A custom stainless-steel counter was added on to hold food.

Window future

Considering how functional these tweaks are, how would Ishimura’s proposal of a new exoskeleton make a tower more flexible?

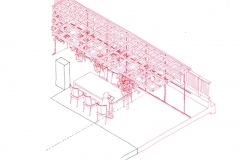

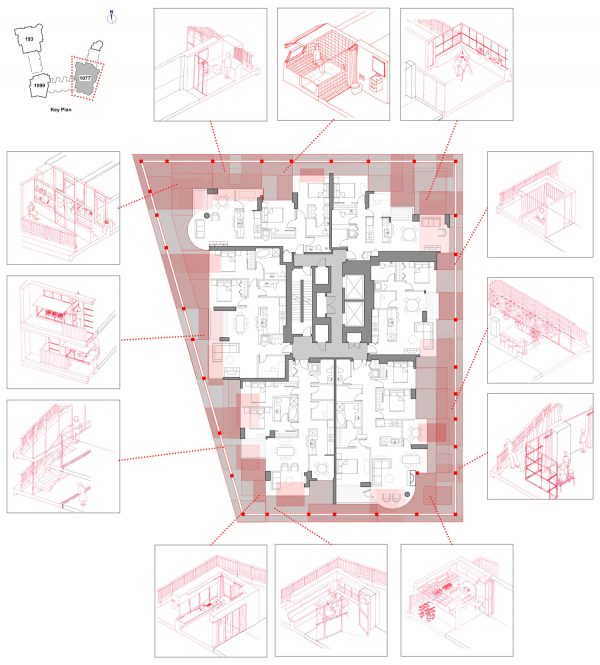

For his thesis, Ishimura chose a Yaletown tower built in 2001 to apply his proposal. It’s a glassy condo building, a classic specimen of Vancouverism.

This neighbourhood was, after all, the centre of the condo boom that’s transformed Vancouver these past three decades and resulted in increased density, higher land prices, more vacant dwellings, more vertical neighbourhoods, fewer purpose-built rentals, more investor-owners, both domestic and offshore, and discord between condo residents via strata councils.

Ishimura visited an open house for a unit in the Yaletown tower and was able to attain a copy of its depreciation report, which called for an $11-million envelope repair in 2040.

An alarming cost, perhaps, considering so many buildings in the region are like this one, but also a challenge.

“There’s a great opportunity here for people who are savvy about energy,” said Ishimura. “Stratas could reinvent themselves for our new climate reality.”

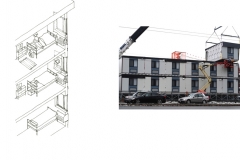

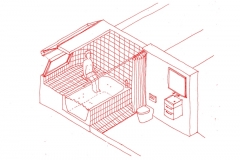

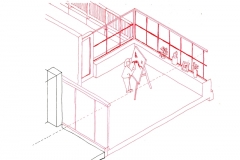

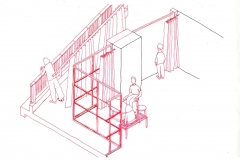

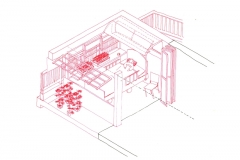

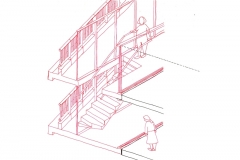

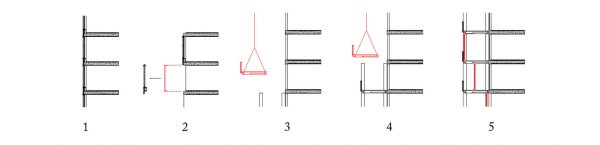

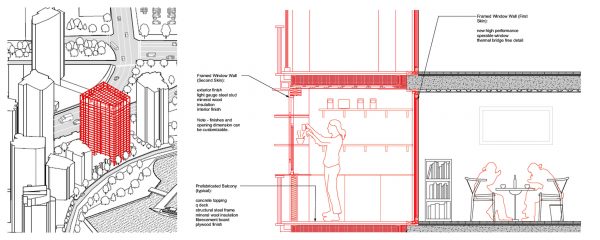

His proposed exoskeleton for the building would be constructed like this. Skin the building by removing the existing windows and replacing them with new framed window walls. Then, install balconies for each unit. To enclose the balconies, install a second skin of framed window walls.

With an exoskeleton comprised of a balcony between two skins, heat would be kept from leaking (a design the industry calls thermal-bridge free construction).

The exoskeleton also creates shading from the south and west, which are prone to overheat in the summer, reducing the need for air-conditioning.

Ishimura imagines that the city could allow the extra floor space for the balcony rooms because it already offers a floor space bonus for developers of net-zero buildings. This would be a tempting carrot for condo residents willing to take on green retrofits of their buildings.

Ishimura’s approach was inspired by what French architects Lacaton & Vassal similarly did to retrofit three social housing blocks in Bordeaux from the 1960s. The buildings, which before had been viewed negatively, received a dignified facelift and extra floor space for a reasonable cost without displacing tenants during construction.

Residents of Ishimura’s transformed tower could make use of their new balcony rooms however they like, from artist’s studios to winter gardens.

Perhaps, then, residents would not feel the need to draw their curtains.

“The beauty of windows is that they’re a part of architecture where individuality is and can be celebrated,” said Ishimura.

It’s a way to bring some warmth to the cold city of glass.

**

Christopher Cheung is a reporter at The Tyee, where this story originally appeared.