On a clear, brisk morning in December 2019, we got a glimpse of the future of aviation. A DHC-2 de Havilland Beaver seaplane retrofitted with a Magnix electric motor made the world first commercial electric flight. The retrofitted Harbour Air seaplane took off from the Fraser River’s north arm and flew for 15 minutes on electric power. Months later, a second flight made by a retrofitted Cessna with seven seats took off in Washington State at Moses Lake. These flights mark the beginning of electric commercial flight and signal a critical change in technology that has the potential to change how and where we fly.

The Vision

The airline industry is notorious for its greenhouse gas emissions. Enormous amounts of fossil fuels are burned every year for commercial flights, and many are questioning the ethical implications of flying, given its environmental impacts. However, if those same flights could be electrified, the implications for intercity travel could be very exciting.

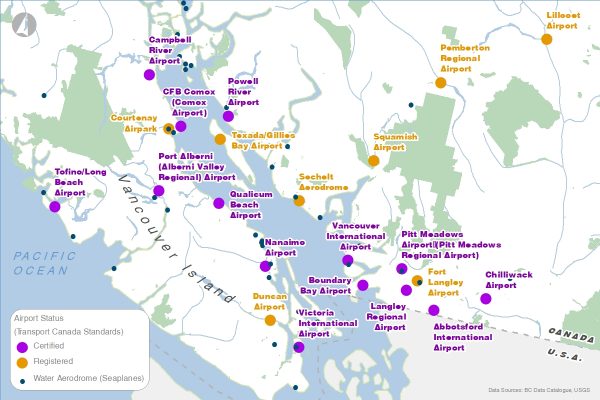

Current demonstration flights have a range of approximately 160 km, which is enough to spark one’s imagination with visions of new electrified flights crisscrossing the province at a regional scale. British Columbia already has dozens of rural airstrips that are waiting to be explored. Its mountainous geography makes it challenging to build highways; rural airstrips and regional airports were built (in part) to introduce redundancy to the transportation network where roads could not.

The first question that may come to my mind is, will we be able to fly to places we couldn’t before? Is this the beginning of a new era of connectivity across BC’s rugged terrain? As is true with most new technologies, the realities of getting started are much more complicated.

Financial Realities

The most obvious benefit of electric flight is fuel savings. While it’s true that fuel is a significant cost, it is only a component of what makes up an airline’s total operating expenses. Small airlines still have to contend with staffing, maintenance, airport fees, insurance, and other costs.

Another major cost borne by the early pioneers of electric commercial flights is research and development. It is extremely expensive to develop new technologies. Typically, new technologies are developed as an investment, something that will eventually pay off. Companies that develop new electric aircraft will seek to recoup their investments, which will likely manifest in high costs for electric aircraft until they become ubiquitous.

In addition to initially high aircraft costs, infrastructure like charging stations, batteries, and the unseen air lanes called IFR (Instrument Flight Rules), will all need to be upgraded and rethought. However, as it becomes normalized, electric flight will become more economical.

The Opportunity

Despite these hurdles, there are exciting opportunities for electric flight, and the west coast is the ideal proving ground. BC’s tangled network of islands, mountains, and fjords makes it a perfect place for short-haul flights. Island hopping is most efficient by airplane. Harbour Air has already done this calculus and is set to retrofit more planes in the coming years.

Driving (which is also rapidly electrifying) is still stiff competition for shorter flights, as there are fewer time and cost hurdles for consumers. However, as technology develops, becomes more common, and ranges increase, so too will the list of possible destinations.

What it means for now

In the short term, progress will be slow as the industry pivots towards electrification. Battery capacity and charging availability are some of the biggest factors that limit the range for electric flight. But, as new electric planes are developed, new longer routes may emerge. Also, the airline industry is electrifying in more ways than one. Larger airlines like Jet Blue and Southwest Airlines are busy electrifying their ground side operations, which has measurably reduced their respective carbon footprints.

For now, the first steps of commercial electric flight are an island-hopping endeavor. But these first flights proved that the future of flight can be different and that it is possible to connect our communities without fossil fuels. Long term, the aviation industry may even be able to shake its carbon-heavy reputation and become known instead as an industry that connects communities with even more convenience. The sky’s the limit.

* This article was made possible through conversations and the expertise of Mark Duncan, President of AeroEdge Consulting and Eric Scott Vice President of Flight Operations & Safety at Harbour Air.

***

Andrew Cuthbert works as a planner in Vancouver and loves helping communities solve problems. When not working Andrew can most likely be found on his bike taking in the sights and fresh air.

Cait Cuthbert works as a graphic designer and illustrator in Toronto. Cait is passionate about housing, urban trees, music and riding her bike.