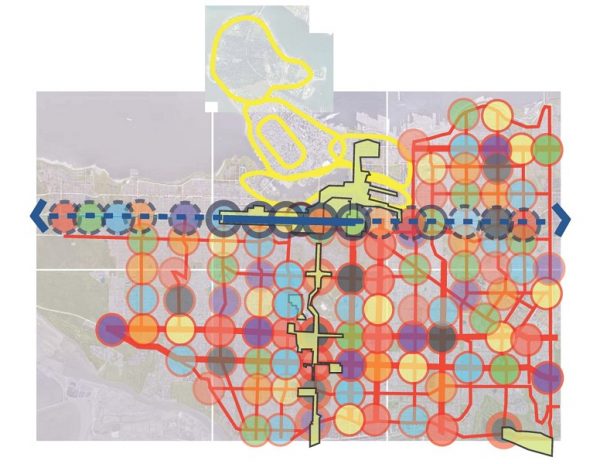

Atop this article is a “Five-minute City” drawing I made in 2007 as Vancouver’s senior urban designer when my team was asked to scope a plan for the entire city. This work respected years of meaningful public consultation with Vancouver citizens that sought to clarify how streets, buildings and the public realm would unfold in coming years.

Our goal was to re-declare that Vancouver is, first and foremost, a “City of Neighbourhoods.” This should have been obvious, especially given the excellent foundational work noted above that included nine related “neighborhood visions” that more specifically declared local community aspirations for housing, shopping and jobs.

But city-wide planning was to fall low on city-hall’s agenda in ensuing years.

Now that Vancouver is again engaged in drawing up a city-wide plan, the Five-Minute City drawing is all the more relevant (even if I don’t work for the city anymore).

The drawing above reminds us of Vancouver’s citywide pattern of approximately 120 more local “community catchments.” Each is supported by one of 109 public schools, and a commercially zoned intersection for walkable shopping and jobs. This urban framework is a gift from the past to the future. The pattern, if preserved and reinforced, can cultivate social familiarity and compassionate support among residents — especially at times of crises when communication systems are down.

The pattern it shows serves as an excellent basis from which to create the city-wide plan started in 2019 with community conversations towards identifying fresh ideas, shared values, priorities and strategic directions to be completed by the next municipal election in 2022. Indeed, Vancouver’s director of planning, Gil Kelley, used my Five-minute drawing in his presentation to council in July of 2019 when $17.9 million, and up to 35 dedicated staff, were appropriated to support the creation of what is now known as Vancouver Plan.

Yet it’s important to understand how constrained are the goals of the Vancouver Plan. It will explore large themes towards shared values. It is not intended to adjust prevailing zoning that would ensure certainty for local communities and the market before the next municipal election. Nor will it produce frameworks reflective of local preference for how a community wants to grow, as done for some parts of the city under previous planning initiatives associated with the city-wide effort called CityPlan.

Spot rezoning policies intended to motivate secured and below-market affordable housing initiated by the previous council under the control of Vision, and furthered by the current more politically diverse council, continue in parallel to Vancouver Plan consultation. These spot re-zonings have the potential to set built form precedents that are already substantially transforming existing neighborhoods.

The obvious contradiction is that, while the Vancouver Plan advances public engagement, built form choices for some areas appear to have already been made through the practice of spot re-zoning that continues.

And so, today we have to wonder what’s really left for Vancouverites to consider under the Vancouver Plan, and is it truly “city-wide”?

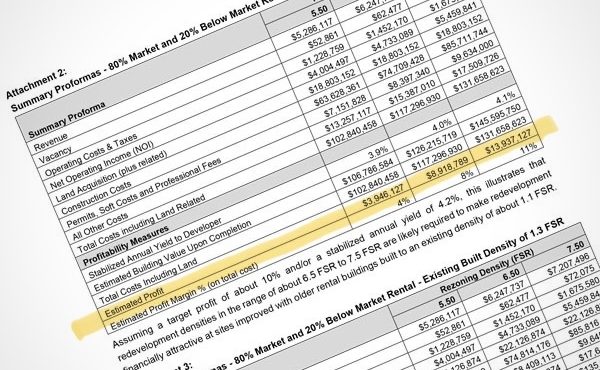

Let’s examine another mapping of the city that expresses where we appear to be today:

The above graphic is the result of eliminating the following (white areas):

- Large and small parks, and municipal golf courses do not appear to be “in play” for a CWP re-think. Parks are sacrosanct. A CWP should expand public parks and open spaces.

- Large previous re-zonings such as Oakridge, East Fraserlands (aka The River District), Shannon Mews, and Arbutus Village that will be difficult to substantially renegotiate under a city-wide planning public process.

- Older built-out rezonings such as the Arbutus Lands and Champlain Heights that will be difficult to re-think under a city-wide planning public process.

- Areas that city hall does not have approval jurisdiction including First Nations Lands (Jericho and Senakw), the Port Lands and Granville Island.

- Fairly freshly minted council-approved community plans that are now being implemented including Mt. Pleasant, Marpole, West End, Norquay Village, Grandview Woodlands, Kensington Cedar Cottage and the Cambie Corridor.

- The Broadway Corridor Planning Area premised on a subway running underground most of its length and assumed to extend to Alma.

- Citywide policies for market rental and Moderate Income Rental Housing Pilot Program projects that I understand are considered non-negotiable under the Vancouver Plan process.

While perhaps not perfectly accurate or inclusive, this “Leftover Map” of blocks and neighbourhoods illustrates the scope of zoned area that remains for city-wide planning for all Vancouverites under the initially approved $17.9 million budget. (A budget, by the way, substantially reduced since the initial approval.) The absence of stakeholder contribution for the future of the white areas, with previous and current council policies continuing to compromise years of community planning efforts in supporting bigger and bigger buildings, is symbolized by the “outbreak” of spot re-zonings throughout the city.

This is concerning as, historically, the planning department has viewed re-zonings as the exception, not the rule. Previous re-zoning planners would often use the phrase “to serve and protect” in describing their role which includes thoughtfully managing land values towards more accessible housing opportunities. Re-zoning, as an affordable housing strategy, has had the opposite effect by driving up land prices as many landowners want to cash out motivated by the “invitation” of city-wide re-zoning policies.

A related effect of re-zoning has been high rents for shop owners. The province bases its property assessment of land on the “highest and best use” with the prospect of re-zoning driving up the land value, property taxes and rents. This has motivated an exodus of mom-and-pops who can no longer afford their overhead. Local shopping is dying.

It’s time the mayor and council be clear about where their priorities lie. How to square the re-zoning decisions that keep landing on the docket despite the aim of the Vancouver Plan to consult with neighbourhood residents about changes in their locales?

Some questions in need of answers:

- COVID-19 makes it almost impossible to gather with residents and engage over design questions in person. What effect has that had on the Vancouver Plan effort?

- Many existing community plans took years to produce. Will the city continue to schedule spot re-zonings for public hearings that propose bigger buildings than currently allowed under such previously approved community plans? An example would be the Safeway site at Broadway and Commercial where a project now proposed exceeds by 12 storeys the council-approved plan that grew out of The Citizens Assembly.

- How can city-wide planning stakeholders be assured that their good faith engagement will be rewarded? How do all who contributed to the Citizens Assembly, which was promoted by the city as “innovative public process,” feel about the proposed re-zoning for the Broadway Commercial Site when the Grandview-Woodland Community Plan mandates a much shorter building?

- Will the city continue to invite re-zoning enquiries for buildings that well exceed existing, council-approved community plans? For example, in Mt. Pleasant, developers are seeking re-zoning to allow towers taller than Rize’s The Independent, despite assurances by the Planning Department to the Mount Pleasant community when the project was approved that there would be none higher.

- Will re-zoning to allow market rental, and secured mixed tenure projects under the Moderate Income Rental Housing Pilot Program, continue to override other forms of housing innovation requested by neighbourhoods, and actually espoused by council?

- Can the Vancouver Plan re-establish trust with Vancouverites when recent city-wide re-zoning policies that invite taller, bigger, and bulkier out of scale buildings, are imposed with little to no public consultation?

It’s worth remembering that when Council approved embarking on the city-wide Vancouver Plan, it named this goal:

Demonstrate Transparency in Decision-Making and Collaborate with Partners. Trust is an essential part of all relationships, including between local government and the community. The City of Vancouver is committed to building increased transparency in decision-making and consultation processes and to constantly enhance governance to effectively engage citizens and lead with a clear vision, priorities, monitor outcomes and constantly learn, adapt and improve our systems.

There is much work to be done in the “leftover” areas that remain on the map shown above. Especially for those neighbourhoods that have not enjoyed legitimate planning for many years. I understand that these community stakeholders are excited about the opportunity to look forward.

Vancouverites deserve more than leftovers, however. Especially while others feast on non-public processes.

***

This article was originally published in The Tyee.

**

Scot Hein is an adjunct professor in the Master of Urban Design program at UBC. He was previously the senior urban designer with the City of Vancouver.