The Riverview Lands, on the slope above the Coquitlam River, were known as a storied place.

Settlers will remember the area most for its mental health facility, which the province began work on in 1904. It had an extensive garden and was near the Colony Farm, where patient labourers once produced up to 700 tonnes of crops and 20,000 gallons of milk per year.

Chief Ed Hall of the Kwikwetlem First Nation says his mother, now 75, has a lot of memories of the Riverview community — from a convenience store she used to visit to the grounds she explored with her friends.

“There was an old, abandoned car — just a shell, and a steering wheel, and four tires — that they used to take turns riding and pushing,” he said.

The settlers made them the outsiders then.

But for the kʷikʷəƛ̓əm people, their relationship with the site dwarfs colonization by about 9,000 years. Before the site became part of the City of Coquitlam, they knew it as a lush spot for food, medicine, ceremony, and due to its high elevation, a refuge during floods and raids by other communities, said Hall.

After the Riverview Hospital officially closed in 2012, the province and Kwikwetlem First Nation, with help from the public, worked on envisioning the site’s future.

Some major announcements for the site came last month: a new name in hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓, the downriver dialect of the Salishan language Halkomelem, and some land returned to the nation’s hands after more than a century.

The remainder of the land will be kept as public space by the province, but BC Housing and the Kwikwetlem First Nation will share in decision-making power, says Carol De Paoli, the Crown corporation’s acting director of land development.

De Paoli says that B.C.’s adoption of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2019 spurred the “side-by-side” collaboration.

“That really signified to us that we need to be approaching this situation to really embody the intent of what UNDRIP represents,” she said.

The new name is a symbol of this: səmiq̓ʷəʔelə, which means Place of the Great Blue Heron. The bird once used the area as a roosting ground and can occasionally be spotted today hunting on the lands, “hanging around the grasses looking for voles, moles, mice — anything they can get their beaks on,” said Hall.

(səmiq̓ʷəʔelə is pronounced “Suh-meek-wuh-ella.” See here for Chief Ed Hall’s guide.)

It’s a new—not an ancestral—name for the place, says Hall, who adds that some members of his band have asked him, “Am I saying it right, Ed?”

Of his nation’s collaboration with the province, Hall says it’s still a “young” relationship, but a good one.

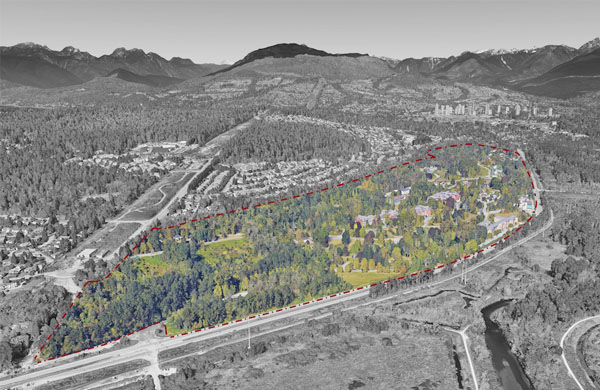

səmiq̓ʷəʔelə is a massive site to be working on. At 244 acres, it’s five times the size of Vancouver’s Olympic Village. A who’s-who of the local city-building world are helping plan it—from Vancouver’s former co-chief of planning Larry Beasley to designers like Henriquez Partners, behind the Woodward’s redevelopment, to PWL, which worked on the landscaping for Southeast False Creek.

Chief Hall has a story of just how vast the site is.

In the 1990s, he was on an evening bus going through the area, when a person suddenly jumped out of nowhere and was hit by the vehicle.

“The bus driver was concerned, and parked and got out to see if he could assist the guy,” said Hall. “But the guy just got up.”

And then he vanished into the dark.

BC Housing and Kwikwetlem have a number of shared priorities for the future of the large site. Reconciliation with the nation is part of it, as well as ecological enhancement and acknowledging the site’s Indigenous and settler heritage.

Riverview’s century of mental health care is not without its controversies, from its use of electroshock therapy to its sterilization of about 200 patients, almost all women.

Also, the downsizing of Riverview, which was planned as early as 1967, has been pegged as one reason why the Downtown Eastside grew as a centre for people with mental health issues. Many patients discharged from Riverview were poor and could not afford to live anywhere else.

Both BC Housing and Kwikwetlem intend to keep mental health care as part of səmiq̓ʷəʔelə’s future. Though the hospital closed nearly a decade ago, health authorities continued to run some programs on the site. The Healing Spirit House, a facility for young patients, was opened in 2019, and the Red Fish Healing Centre for Mental Health and Addictions will open this summer.

In addition to the site’s multi-dimensional history of flood refuge and health care, it has also enjoyed the limelight as a filming location.

“People with a quick eye will recognize Riverview in a lot of productions,” said De Paoli, from shows like The X-Files and Riverdale, to films such as Deadpool 2, where the facility stood in as the X-Mansion.

The location’s legacy as a Hollywood hotspot will continue, she said. Pre-pandemic, productions shot daily. Even with COVID-19 last year, filming took place during 144 days in 2020.

Affordable housing is also a priority for səmiq̓ʷəʔelə, though planners haven’t determined what it will look like. Co-ops and below-market rental are among the options under consideration, and Hall doesn’t expect there to be massive density in the form of towers. He wants to see development in keeping with the existing scale of the site, currently home to 69 buildings.

Hall says it has not yet been determined how much or exactly what land will be returned to his nation, though he has an idea for a cultural centre to showcase their stories, language and artifacts. Hall hopes that they’ll be able to repatriate some from the Royal BC Museum.

The public is invited to participate in consultations. BC Housing and Kwikwetlem expect to arrive at a final concept within two years. They will be working with the City of Coquitlam throughout, and need the council’s rezoning approval.

səmiq̓ʷəʔelə joins a number of other local projects in the works with leadership by Indigenous Peoples on their ancestral lands.

The Squamish Nation has the upcoming 11-tower Sen̓áḵw at the foot of Vancouver’s Burrard Bridge, and the MST Development Corp. (a partnership between the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh) has a few, including the Jericho Lands and the Heather Street Lands.

These days, Hall has been thinking a lot about what it means to steward a landscape like səmiq̓ʷəʔelə. After all, he says, if settlers never came, the land would’ve likely remained forested.

“With a lot of our culture lost to colonization,” said Hall. “It’s nice to be able to have a say again.”

…

Christopher Cheung is a reporter at The Tyee, where this story originally appeared on April 12, 2021.