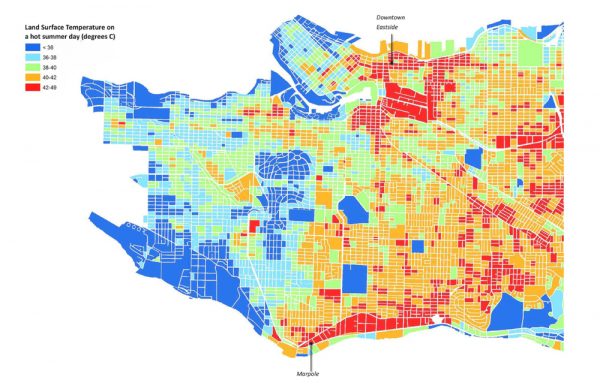

We all know about wealth inequality in expensive Vancouver. But there’s also inequality when it comes to who has the shade, and who’s left to scorch in the sun. In fact, this shady inequality is baked into the landscape of the city itself.

The average temperature of the city’s streetscape varies by more than 20 C between the coolest and hottest city blocks during the summer, according to the park board.

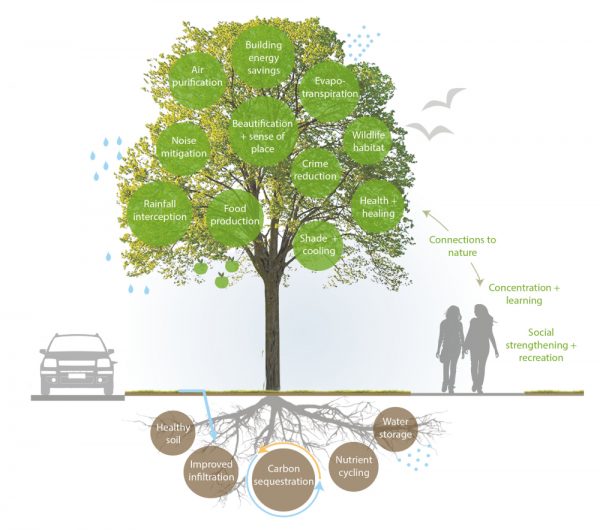

A key reason behind this? Trees and their shade.

Large urban centres tend to be more susceptible to extreme heat than their surrounding rural areas. Urban centres have fewer trees than rural areas, and more roads and buildings that absorb and store heat. This is called the “urban heat island” effect, and it’s why it’s important that cities grow their tree canopies as much as they can.

A 2018 report by Vancouver’s park board stressed the importance of the city’s urban forest as a protective measure for moments such as the current “heat dome” that’s sizzling the Pacific Northwest and breaking temperature records.

Vancouver typically experiences 18 summer days with temperatures above 25 C. But the 2018 report features climate change modelling that predicts we’ll have 43 such hot days each summer by 2050, over twice as many. Extreme heat events will also happen three times as frequently.

The report also identified vulnerable populations who live in areas with less tree coverage, which exposes them to a higher risk of heat-related illnesses and death.

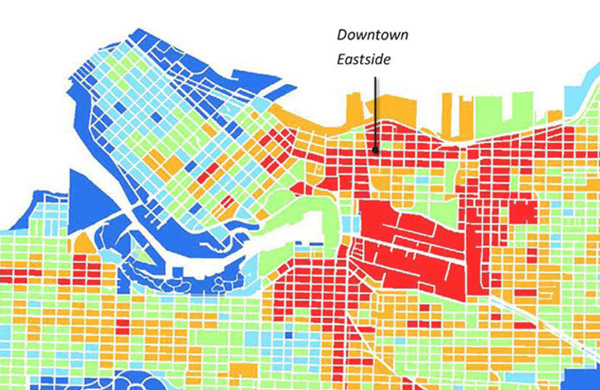

The Downtown Eastside, Marpole, and parts of Vancouver’s southeast have the hottest streets. Factors such as isolation, mental illness, homelessness, substance use, and physical disability all play a role in increasing heat-related harms.

The blue-highlighted parks across the city show us how important green space is.

Maps reported by The Tyee on where low-income residents live and where COVID-19 spread during the third wave shows the same neighbourhoods highlighted — those with more money have more choice and freedom when it comes to decisions about health and lifestyle.

Vancouver, still striving to become the greenest city on the planet, remains only green in patches.

…

Christopher Cheung is a reporter at The Tyee, where this story originally appeared on June 29, 2021.

One comment

The notion that trees deter crime is an interesting one that I’d be interested in reading more about.

In American cities police have actively discouraged street trees in urban cores because it gives the bad guys places to hide from police and predators cover for stalking their human prey. I LA they went even further – encouraging/strongarming the city to cut down street trees to improve sight lines for new surveillance cameras.

“Police have convinced community leaders that, if you want to

save your community, you can’t have too many trees, because it restricts [the police’s] ability to do their jobs.” Michael Pinto, NAC Architecture in LA

– from Places Journal 2019

If you’re arguing for street trees, which I support, the public safety angle will have to be addressed properly.