The cost of housing has reached a crisis point in Vancouver, with no clear agreement on what to do about it. Which made it a rare moment when council—perceiving threats to affordability in False Creek South—voted unanimously to turn back a staff proposal to dramatically densify and rearrange the neighbourhood using a market-based approach.

In the context of that marathon debate, and just before the vote was called, Coun. Michael Wiebe captured the tenor of the evening when he said, “What Vancouver needs is more False Creek South.” None of our elected leaders argued the point.

But that leaves open the question of where to put more False Creek South?

False Creek South was built on a largely abandoned stretch of derelict waterfront. Succeeding developments in the city took over other vast parcels of similar swaths of industrial shoreline. But those days, and those parcels, are gone. If we need more False Creek Souths, where should we put them? The only answer available to us—in our neighbourhoods.

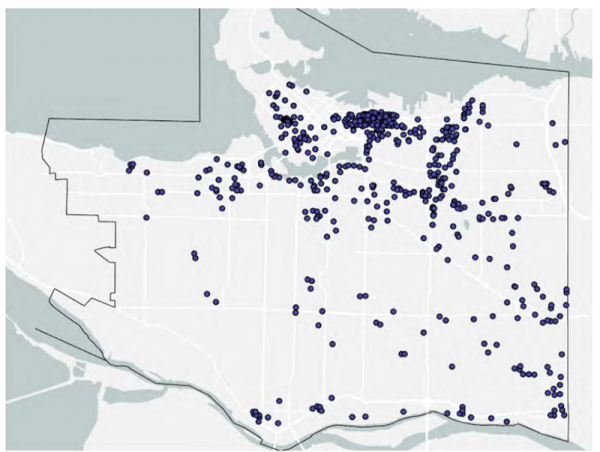

Not everyone is aware that affordable co-op buildings are already scattered in many parts of the city. They tend to be innocuous small structures that fit in respectfully with their privately owned neighbours. You might be surprised to see in the map below how many exist and where.

Seen this way there is no shortage of locations for smaller co-op buildings, preferably, perhaps, close to neighbourhood schools where the young families who would be the likely beneficiaries of such an initiative could be close to, and keep full, that crucial piece of public infrastructure.

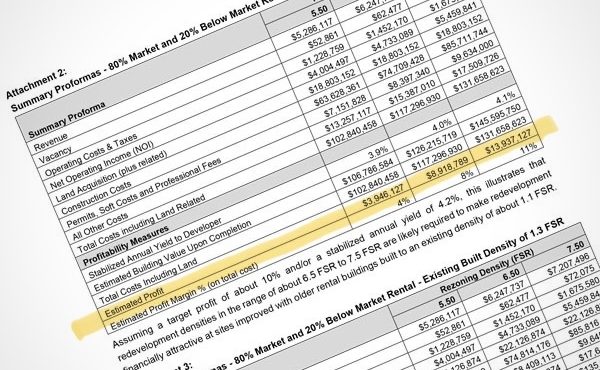

What stands in the way? Above all, land prices. Unless the provincial government comes in with billions of dollars to acquire available parcels, current land prices present us with a challenge. To make co-ops self-financing requires both affordable land and enough new square footage to make the land purchase amortizable through affordable rents.

If new co-op developments have to compete with market-based rental or condo developments in buying, the numbers won’t work. That’s because the more density allows on a parcel, the higher the price rises for the land, which then must be recouped through higher rents or unit price-tags.

The effect is baked in, as they say. Vancouver land is no longer sold by the acre, but by the square foot “buildable”—how many interior square feet of new housing zoning will allow. Right now, the price of land per buildable square foot is about twice the price of the construction.

Fortunately, there is a way to dampen this effect in order to let co-ops flourish. If the city only allows increased density on single-family zoned parcels for new co-ops, which it has the authority to do, but prohibits the same new density for private developers, land prices will not inflate nearly as much. Developers seeking to build condos or market-rent apartments, with the prospect of much higher sales or rent revenue, won’t be bidding up the prices.

Even so, Vancouver land isn’t cheap. Which raises the question: How big must a new co-op be to “pencil out” and cover its land and construction costs while still collecting affordable monthly rents? Could one avoid buying up a lot of single-family lots and assembling them into one large development footprint as we see happening along arterials around the city now? We know that such “land assembly” can disrupt existing neighbourhoods by unleashing inflationary processes.

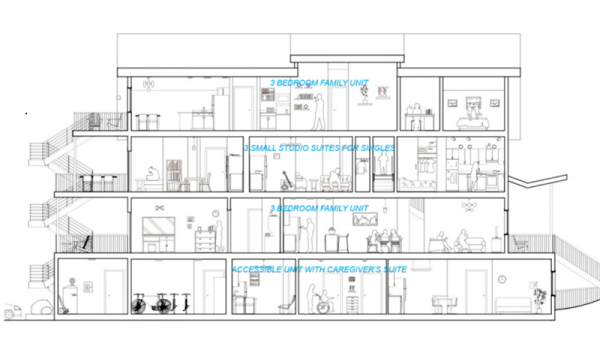

We can avoid this process and have many more co-ops, concludes local architect Sean McEwen. Working through the numbers, he suggests that a wood-frame 6,000-square-foot building of a size necessary to amortize current land costs with affordable co-op rents would fit into a typical Vancouver lot—without land assembly and without overshadowing neighbours.

It’s time that council took a more serious look at the potential of co-ops, and moved away from the land inflationary policies it has been quick to embrace instead. Earlier this month, council voted to allow four-storey “secured rental buildings” on blocks immediately behind arterial streets, in the hopes that the production of these units will help resolve the housing crisis.

Once again, critics predicted that this market-tied densification will merely raise land prices, making it impossible for developers to produce housing that can be rented at affordable rates. City staff maintain that even if this is the case, providing high-priced rental housing units throughout the city will take pressure off lower-cost housing in a process called “filtering.”

But so far Vancouver exhibits none of the beneficial effects touted for filtering. Apartments in our more affordable neighbourhoods, such as Marpole or Mount Pleasant, show punishingly low vacancy rates of 1.1 per cent and 1.4 per cent respectively, while thousands of expensive downtown apartments go begging at 6.3 per cent vacancy.

If we agree that the housing market, left to its own devices, is incapable of supplying affordable homes no matter what new density we offer, we have to take a different path.

Authorizing co-op (or other non-market forms) in our neighbourhoods, with the advantage of “Goldilocks” density bonuses (not too little, not too much, just right) might just be, as Coun. Wiebe suggests, what Vancouver needs a lot more of.

There is no time to waste. Vancouver should shift gears as 2022 dawns. Our young families, who are rapidly being exiled from our city due to housing costs, can’t wait any longer.

***

This piece was originally published on The Tyee.

**

Patrick Condon is the James Taylor chair in Landscape and Livable Environments at the University of British Columbia’s School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture and the founding chair of the UBC urban design program.

One comment

Volunteer boards rarely have the background and skills to run a multi-million dollar business and no oversight of professional knowledge.

I live in a non-equity co-op and have seen personal agendas trump necessary decisions