Vancouver is destined to have a new neighbourhood on its west side, one so densely populated that Council recently approved routing the proposed subway to UBC through the so-called Jericho Lands and building a station there instead of in the Point Grey Village commercial area four blocks uphill.

That extension of the Millennium SkyTrain, running underground to the campus from its currently planned terminus at Arbutus Street, is not a done deal. Still to be secured is $4 billion in funding ($800 million from local sources, $1.6 billion each from the province and the feds). But let’s assume the plan doesn’t fall apart.

There are many reasons to hope a vibrant, beautiful, highly livable community could arise in the 90-acre parcel bounded by West Fourth Avenue, Highbury Street, West Eighth Avenue, and Discovery Street in West Point Grey. The land is owned by three First Nations — the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh — along with a federal crown corporation called Canada Lands Co. There is a chance for something special.

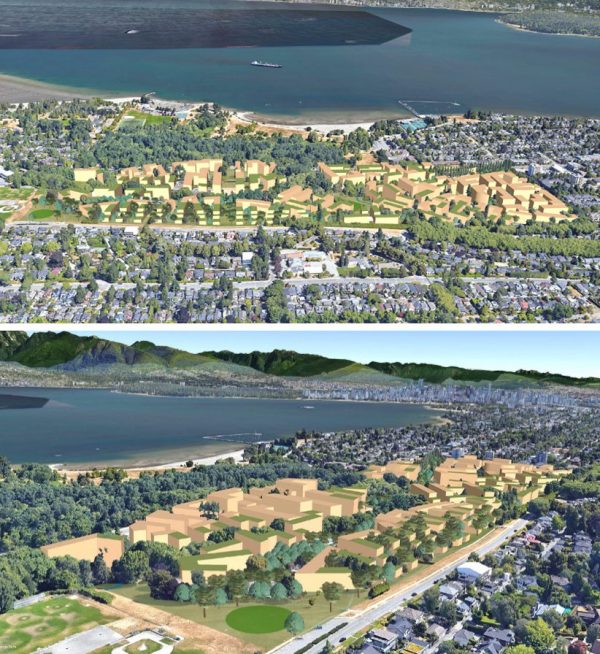

So far, then, what do we know of what’s in the works for the Jericho Lands? Images released last October by the City of Vancouver propose it to be home to many towers of sizes far out of proportion to the surrounding cityscape. The concept shown is named “Eagle.” There is a similar concept called “Weave” at the same density.

Tall buildings of such mass cast shadows to match. We have seen the shadow simulations. Expect serious impacts on Jericho Park and habitat spaces. And yet, even these renderings do not fully represent the maximum number of additional tall buildings that the city has signaled it may consider. While the renderings show a combination of mid- to high-rise buildings, the plans and their explanatory key indicate buildings may go “up to” significantly greater heights.

The Jericho Coalition is a group of engaged and concerned volunteer citizens — including planners, engineers, architects, and environmentalists — who have come together after only recently learning about the city’s proposals. They are opposed to the proposed approach, not solely because of the maximum heights but for multiple reasons. The towers are too big, unsustainable and units will be too expensive, to name a few.

Moreover, their modeling leads them to conclude the “scaled back” version rendered by the proponents above could actually become the scenario below including the prospect of 63 towers. The coalition has used these “up to” maximum heights to produce the images below.

Vancouver area planners have a term for putting clusters of dense high-rises around train stations — “transit-oriented development.” A prime example is Burnaby’s Metrotown. And now it appears something of a similar monumental scale is proposed for Vancouver’s west side.

Is there an alternative? Are there better ways to build out this site that produce as many units of housing, as much density, and a similar number of units per acre? And if so, would the city consider a less overpowering option?

In the past, Vancouverites have succeeded in defeating this sort of bad design. There were going to be big towers at 12th Avenue and Vine until the community pushed back. The site instead became Arbutus Walk, now recognized as a thoughtfully scaled, dense, mixed-tenure community with a distributed open-space system for all nearby residents to enjoy. Everyone got what they wanted.

The same thing happened with the Olympic Village on city-owned land, a concept that started as towers but eventually became a midrise community that still provided the same saleable floor area.

Now arrives another moment for leadership by city hall to consider such precedents.

Instead of a cluster of high-rises, this is what the Jericho Lands community could be:

The alternative approach shown above, produced by the engaged volunteer citizens of the Jericho Coalition, suggests a much lower overall scale with more efficient footprints, tightly arranged towards making a vibrant street-level community with sunlight able to reach open spaces even in winter.

Rather than living among looming towers, what would it feel like to move around the scale and style of built landscape the Jericho Coalition proposes? We draw on recognized international best practice precedents such as these below:

These are socially productive places, at modest heights that allow the spaces in between to enjoy the sun, grow food, play, and thrive. We’re confident that housing costs would be substantively less because structures could be made of locally produced mass timber rather than concrete.

Now some will say, best transit-oriented practices require us to develop land more intensively within walking distance of expensive transit investment. And that is correct.

Guess what? The comparative images below equally produce the same developable floor area (approximately 693,000 square metres or 7,459,390 square feet), at the same density, and with the same net building footprint (approximately 100,000 square metres or 1,076,391 square feet) with the community’s proposal providing even more public park space (an additional 4,685 square metres or 50,429 square feet). The contrast between visual impacts from eye level is obvious. But the difference in community quality is even more significant.

Finally, we fear that the developer’s proposal, as currently promoted above, will not be well received by the public if there are no guarantees that the people who need housing in this city will be able to live here. Creating vast new numbers of units of housing on Vancouver’s west side is a good idea only if affordable for ordinary people. It’s not a good idea if 95 percent of these units are marketed at the same $2,000 a square foot they are asking for at, say, the towers and transit development now rising at Oakridge in the southern part of Vancouver. There a two-bedroom unit will sell for $2 million or rent at market rents close to $5,000 per month.

The opportunity exists here to insist on affordability for at least 50 percent of the units built on the Jericho Lands. This would go a long way towards creating new housing for members of First Nations, students, and our city’s service workers, who are presently abandoning us.

The key is to bake this expectation into the beginning stages of planning, which in turn will suppress land price inflation. Combine those savings with more enlightened planning and cost-efficient construction, and the unique partnership of three First Nations, the federal government, and the City of Vancouver could yield a breakthrough model of a neighbourhood conceived from scratch to be livable and affordable — a prototype deserving of international attention.

If instead the Jericho Lands are converted into an over-scaled playground for the rich, then why should we spend public money for the subway to serve it?

***

This piece was originally published in The Tyee on April 6th, 2022.

**

Scot Hein is a retired architect, former senior urban designer at the City of Vancouver and the University of British Columbia. He is an adjunct professor of Urban Design at UBC, lecturer at Simon Fraser University and founding board member of the Urbanarium.