With temperatures heating up due to climate change, tree canopies have an important role to play in shading and cooling residents.

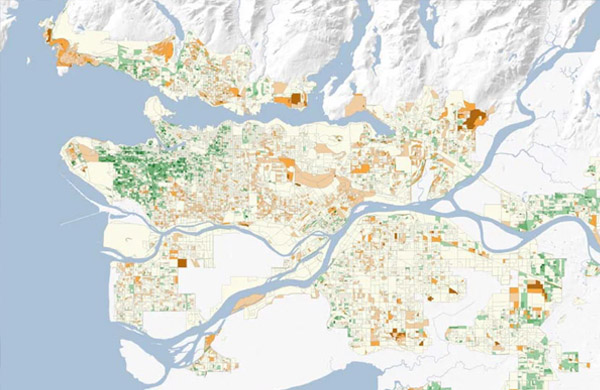

But according to new data, Metro Vancouver has been simultaneously losing tree coverage and adding pavement, making for dangerous conditions when extreme weather hits.

“This is an issue that’s obviously concerning all of us,” said Vancouver Coun. Adriane Carr at a regular meeting with leaders from the region’s 23 municipal governments last April.

A report by Metro Vancouver was shared with the leaders, documenting the state of change.

Between 2014 and 2020, tree canopy coverage in urban areas dropped one percent, to 31 from 32 percent. Aside from shade and cooling, trees also store carbon, serve as habitat for wildlife, and help manage stormwater.

On the flip side, impervious surfaces — in other words, pavement — rose by four percent, to 54 from 50 percent. Paving causes urban areas to heat up intensely in hot weather and flood when rains come. The runoff also picks up pollutants before entering waterways.

The 2021 heat dome that killed 619 people in B.C. was a wake-up call for cities that are dedicating more space to grey than to green.

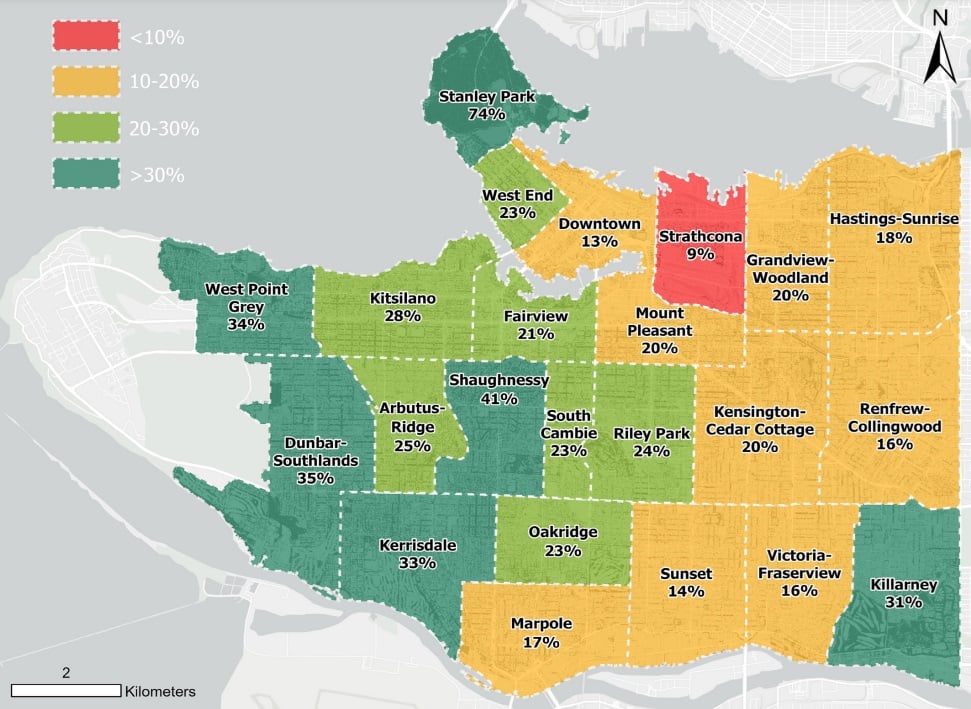

Reviews of the disaster by the BC Coroners Service and Vancouver Coastal Health found that a disproportionate number of deaths occurred in hotter neighbourhoods that lacked greenness.

Since then, municipalities have been stepping up to the challenge. The City of Langley is working on a new urban forest management strategy. In Vancouver, Coun. Christine Boyle proposed a motion to improve the city’s tree canopy that received multi-partisan support.

“As we saw in the 2021 heat dome, buildings can be unsafe for people in extreme weather events,” Boyle told her fellow councillors in June. “So the motion directs staff to focus on areas with lower tree canopy and areas where residents are at higher risk.”

Vancouver is a prime example of the economic unevenness of tree canopies. The affluent west side is leafy, while both the east side and the Downtown Eastside — home to some of the city’s poorest residents, many of whom struggle with health issues — are noticeably grey on maps. Residents from the East Side and Downtown Eastside made up the majority of emergency room visits during the heat dome.

So how do we ensure that the canopies of the future cover everyone?

Greening the grey

Lorien Nesbitt, an assistant professor of urban forestry and environment justice at the University of British Columbia, says that efforts to expand tree canopies need to pay attention to inequities.

It’s easy to plant trees where there is already green space. Cities need to be prepared for the costs that come with greening areas that have been left behind in the past.

“Some of the areas that are the most vulnerable to heat are also the areas that have the most grey infrastructure, and so planting trees in those spaces is more expensive and requires a lot more investment,” she said.

After new trees are in a neighbourhood, “they’re going to be small for a while.” As a result, it’s important that cities find short-term solutions to keep residents cool in the meantime.

“We need to think about whether trees are able to provide those services or whether they need assistance from other types of infrastructure,” such as misting stations or shading structures, said Nesbitt.

Trees are also needed in more places than just residential areas.

“Having trees in our cities allows us to move around,” said Nesbitt. “Planting trees along transit and by transit stops allows us to continue living our lives during times of high temperatures... so that we can go to work or see friends.”

Prioritizing solutions that allow people the ability to go about their day is especially important for low-income people. Municipalities have relied on cooling centres as a solution, but they require visitors to stay in one place, she added.

Growing a different city

This year, local leaders have been scrambling to tweak their land-use plans after the province mandated new targets for housing density. At the Metro Vancouver board meeting in April, some leaders worried that the new density might affect canopy coverage.

But Nesbitt says there’s no reason why they can’t have both.

According to the report by Metro Vancouver, it’s the development of detached houses in particular that has caused more of the region to be paved. Lot sizes have been shrinking and homes have been hogging more of each lot, leaving less room for trees.

The report says that towers built from the 1960s on have actually done a good job of including trees and expanding canopy coverage.

“I don’t see trees and housing necessarily in conflict with each other,” Nesbitt said. “A lot of [space] is devoted to cars right now,” she added.

The Province has been hoping that encouraging density near public transit will push municipalities to reduce their parking requirements.

“Most cities in Canada tend to underinvest in urban forests. Trees require management and maintenance to persist, and we don’t prioritize them,” said Nesbitt. “I think we need to have a more comprehensive conversation around what it means to be a green and resilient city.”

While the Metro Vancouver data is important, it’s not the freshest, as the regional district takes a snapshot of canopies only every six years. There is hope among the region’s leaders that the 2026 update will be more optimistic, thanks to policies developed in response to the 2021 heat dome.

“As we expect trees to protect us from climate change, we also have to think about protecting them from climate change,” said Nesbitt. “They require our care, our management, sufficient space, good soils, and I think they’re worth our time. We need to remember that it’s a two-way street.”

…

Christopher Cheung is a reporter at The Tyee, where this story originally appeared.