In the spring of 2024, a group of urban planners from British Columbia embarked on an enlightening week-long journey to Barcelona, Spain, as part of an immersive field school aimed at giving working planners a rare chance to learn directly from those exploring innovative urban solutions.

Barcelona, renowned for its groundbreaking urban planning and design, offered a dynamic learning environment for the British Columbia delegation that came from all around the province. The Field School was designed to provide participants with firsthand experience and insights into how Barcelona is addressing complex urban challenges, such as housing affordability, sustainable transportation, public space use, and climate resilience.

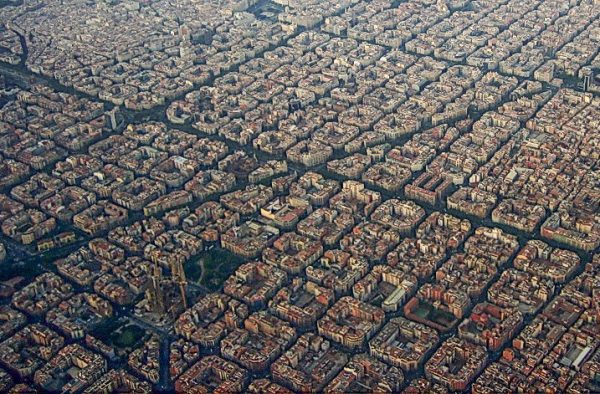

Barcelona’s approach to urban planning is both historical and progressive, rooted in the legacy of visionary planners like Ildefons Cerdà, who laid the foundations with the Eixample district’s iconic hexagonal grid system. Two pre-departure classes provided important historical context for the journey, covering major planning landmarks across the city’s 2000-year history—from its start as a Roman city through Cerdà’s plan for the Eixample to its most recent initiatives. The on-site itinerary followed suit: covering the important urban planning moments chronologically over the week.

The Barcelona Chronicles series will summarize and share some of the key lessons from the adventure, focusing on Barcelona’s approach to providing affordable housing and its built fabric. These were chosen because they are relevant to the challenges we face here in Metro Vancouver and provide meaningful points for discussions.

Some important information is necessary to fully appreciate the content to come: Barcelona and Vancouver, though different in many ways, offer fascinating comparisons in terms of their urban metrics and characteristics. Covering an area of approximately 101.9 square kilometers, Barcelona is slightly smaller than Vancouver, which spans about 114.97 square kilometers.

Despite its smaller size, Barcelona’s population is significantly larger, with approximately 1.6 million residents, compared to Vancouver’s 631,486 (as of 2016). This results in a striking difference in population density: Barcelona has roughly 15,700 people per square kilometer, making it one of the most densely populated cities in Europe, while Vancouver’s density is about 5,760 people per square kilometer—about one-third that of Barcelona.

Interestingly, Barcelona houses this density largely within mid-rise buildings. High-rises are a rarity. For example, within the Eixample—where we will focus our attention in the series—building heights lie mainly between 5- and 8-storeys, as with the majority of the city. But, importantly, the midrise buildings drape the landscape as an equally distributed blanket of buildings.

Vancouver’s urban landscape, on the other hand, is dominated by two extremes: freestanding housing and high-rises. This is being supplemented more recently by an increase in mid-rise buildings and slightly denser freestanding forms—such as duplexes and laneway houses—but these remain the minority in Vancouver. Current densification measures bias residential tower buildings, as made evident by the Broadway Plan.

Another important point of comparison in terms of physical structure is that the street widths of the Eixample and most of Vancouver’s streets are identical at 20m (66ft). We will discuss this at more length down the line, but without going into too much detail, Barcelona streets can be used as a direct, applied case study for different versions of what Vancouver can look and feel like.

On a broader scale, both cities extend their influence beyond their boundaries through larger metropolitan areas. Barcelona’s metropolitan area is home to approximately 5.5 million people, establishing it as a major European hub. In comparison, the Greater Vancouver area has about 2.6 million residents, making it a significant urban center on the west coast of Canada.

Transportation infrastructure is a critical aspect of both cities’ urban planning. Barcelona boasts an extensive public transit system with 12 metro lines, a comprehensive bus network, and a tram system, complemented by numerous bike lanes and a quickly growing pedestrian street system.

Conversely, Vancouver features the SkyTrain rapid transit system with three lines, an extensive bus network, the SeaBus ferry service, and a cycling infrastructure that mixes bike streets and a slowly growing number of designated bike lanes. These systems reflect each city’s commitment to providing residents with efficient and sustainable transportation options, although Barcelona’s system is much more diverse and comprehensive.

Economically, both cities are dynamic, though their major industries differ. Barcelona’s economy is driven by sectors including tourism, manufacturing, commerce, and technology. The city is a significant cultural and economic hub within Europe. Vancouver, renowned for its natural beauty, is an economic gateway to Asia with key industries in technology, film and television, tourism, natural resources, and international trade. The tech scene in Vancouver is particularly vibrant, contributing to the city’s economic growth and innovation.

Both Barcelona and Vancouver face significant affordability challenges—highlighting the global nature of urban affordability challenges—though the nature and context of these challenges differ. In Barcelona, rising housing costs have increased pressure on rental and purchase markets, exacerbated by a high demand from tourists and foreign investors.

The city has responded with various innovative policies, including the Barcelona Right to Housing Plan 2016-2025 and Barcelona Housing Policy 2015-202,3 which outline the strict enforcement of affordable housing requirements for new developments, promote cooperative housing, and foster strong public-private partnerships, under the belief that housing is too important to be left to the market. Describing their approach to affordability will take up the majority of the Barcelona Chronicles series.

Vancouver, similarly, struggles with high housing prices driven by limited supply, high demand, and foreign investment. Its responses include initiatives such as the 2017 Empty Homes Tax, Affordable Housing Strategy, and its most recent Social Housing Initiative. Also worth mentioning is the launch of the BC Province’s Transit-Orient Development Areas, which was wrapped in rhetoric of affordable housing and adding much-needed dwelling units at the outset, under the guise of transit.

In contrast to the approach of Barcelona, Vancouver—and North America, broadly—has maintained its belief in the market’s ability to provide affordable housing. Vancouver’s approach, in particular, has been called “hyper-capitalist” in that it has attempted to engage the market proactively and incentivize better city-building practices through regulations and discretionary controls that, for example, offer more density for community amenities. This approach has been well documented in John Punter’s The Vancouver Achievement and is a hallmark of what has come to be known as Vancouverism.

The implications of the above are long-reaching. For example, increasing housing supply in Vancouver is often done through initiatives such as offering rezoning for higher density, with biases leaning towards a narrow range of profit-generating building types attractive to developers, with high-rise buildings being the clear favorite. Measures to date, however, have had very limited success with housing costs continuing to increase since the mid-1980s despite the vast increase in supply through tower construction since that time.

The climate also sets the two cities apart. Barcelona enjoys a Mediterranean climate with hot summers and mild, wet winters, making it an attractive destination year-round. Vancouver, with its oceanic climate, experiences mild, rainy winters and warm, dry summers. Despite these climatic differences, both cities state that they prioritize sustainability,

What this has meant on the ground is different, however. Barcelona has focused on urban greening, energy efficiency, and reducing car dependency through projects like the Superilla. Piloted in the city’s Eixample district, the initiative has evolved with a plan to create 21 green streets and 21 new squares—transforming over 33 km of existing car-oriented streets, and much of which is currently completed. This will result in The Eixample gaining a total of 33.4 hectares of new pedestrian areas and 6.6 hectares of urban green areas. This is consequently a topic that will also be covered in more depth in the Barcelona Chronicles.

In contrast, the City of Vancouver’s last major effort in this direction was the development of its 2010 Olympic Village, which saw the creation of Canada’s first net-zero multi-unit residential building, deploying a range of progressive energy systems and urban design principles. Since then, however, there has been nothing of true significance or visionary plans beyond the stated ambitious goals to become the “Greenest city in the world”.

So, although the city considers itself one of the most progressive in these areas within North America—a belief that does have some truth to it—an honest reflection would recognize that these ambitions fall orders of magnitude short of its global counterparts, particularly many cities in Europe.

The stage is now set! The similarity in land areas, urban structure, and aspirations of Barcelona and Vancouver offers us a great foundation to highlight their similarities and differences…and ultimately for us to learn important lessons from a city at the forefront of sustainability, affordability, inclusivity, and quality of life.

The series will be divided into two broad, but interrelated sections. Following one more piece that offers some important context by looking at Ildefons Cerdà and Ada Colau, it will start with several articles focusing on Barcelona’s approach to affordability—its policies and related systems. This will be followed by several pieces highlighting Barcelona’s attitude towards the physical fabric. Articles comparing Vancouver and Barcelona will bookend the sections.

I hope you find the Barcelona Chronicles as eye-opening and inspiring as those who came on the journey.

***

Other pieces in The Barcelona Chronicles:

- Part 2 – Cerdà and Colau: Two Key Figures

- Part 3 – The Barcelona Housing Policy 2015-2023 Overview

- Part 4 – Defining Affordable & Social Housing

- Part 5 – Supplying Affordable Housing

- Part 6 – The 30% Measure and Others

- Part 7 – Vancouver v. Barcelona – Foundations

- Part 8 – Barcelona v. Vancouver – Strategies

- Part 9 – The Eixample and the Superilla

- Part 10 – The Superilla Pilot

- Part 11 – The Superilla…Evolved

- Part 12 – Vancouver v. Barcelona – Urban Design

- Part 13 – Reflections on Two Cities

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.