Now that we’ve explored the foundational differences between Vancouver and Barcelona, let’s examine how these differences shape their housing strategies. As mentioned earlier, don’t be misled by similar terminology.

One of Vancouver’s key tactics is “inclusionary zoning,” where developers must include “affordable units” or “social housing” in new buildings. However, this is vaguely defined. For instance, the City of Vancouver’s Housing website offers broad and unclear definitions of both affordable and social housing. A deeper dive into its Housing Strategy and 2023-2033 Housing Vancouver 10-Yeard Housing Targets Report demonstrates the same.

The recently launched Vancouver Social Housing Initiative information is more specific, using BC Housing’s 2023 Housing Income Limits (HILs). These limits, set by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), are intended to reflect the minimum income needed for market-rate housing, based on the number of bedrooms. The income target for a “1 bedroom or less” unit is $58,000. When compared with Statistics Canada data, however, it becomes clear that this is beyond the reach of many who need affordable housing, particularly among minorities who should be prioritized for these units.

The Social Housing Initiative information also attempts to connect these figures to a “maximum rent for social housing,” but this is often subject to variation, depending on the housing agreement. For a more detailed analysis of the flaws in this policy and the City’s loose definition of “social housing,” Brian Palmquist’s work offers a deeper critique.

“Affordable housing” is even more ambiguous. According to the City, housing is considered affordable when it costs 30% or less of a household’s total pre-tax income, but there’s no mention of which income levels are targeted. When I chaired the Academic Group of Mayor’s Task Force on Affordability under Gregor Robertson, we were given a target income far above the actual average household income at the time. Little seems to have changed since.

Barcelona, in contrast, clearly distinguishes between affordable housing for middle- and lower-income households and social housing for vulnerable populations. These categories are strictly defined using accessible monthly rental costs understood by both developers and the public. The city invests heavily in both, often using public land to increase supply. It also enforces strict rent controls and tenant protections, preventing evictions and offering legal support to at-risk tenants, creating more stable housing conditions.

Barcelona has also adopted a much more aggressive, non-negotiable, and structured approach to housing. One standout policy in Barcelona is the 30% Measure, which mandates that 30% of new housing projects be designated as affordable, according to the city’s definition. This rule is hard-and-fast, ensuring a steady supply of affordable units and promoting mixed-income communities.

In Vancouver, a similar 30% requirement was proposed under the Province’s Transit-Oriented Area (TOA) plans. Initially, 30% of the floor area in new developments was meant for inclusionary social housing, but it was quickly reduced to 20%, with officials claiming that higher targets would deter development by increasing financial risk.

To quote, the 30% requirement “…would likely result in very limited uptake by increasing risk and lowering the market component of the project through which any cost overruns could potentially be recouped.”

The lack of fixed requirements undermines meaningful housing policies in Vancouver. While in Barcelona, planning dictates market behaviour, in Vancouver, the market dictates planning. The City tries to address concerns about speculation and land value impacts by tying social housing targets to pro forma reviews and Community Amenity Contributions (CAC) negotiations. This is clearly stated in the memo. However, CACs are also problematic due to their inconsistent, case-by-case nature, often leading to fewer affordable units than needed.

Describing Community Amenity Contributions (CACs) in a little more detail is worthwhile. These are “in-kind or cash contributions provided by property developers when City Council grants development rights through rezoning” that can be used towards several things including affordable housing.

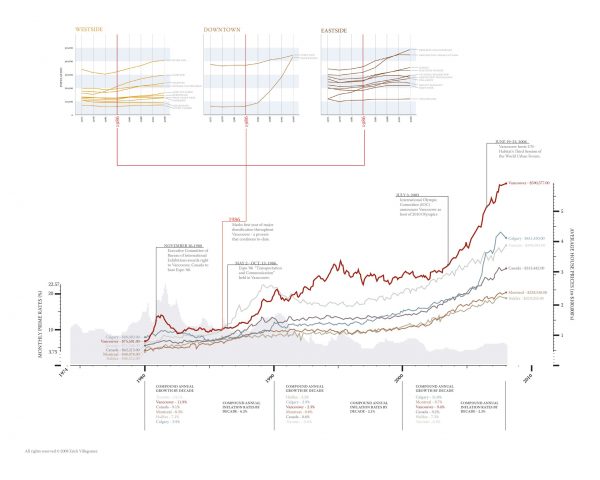

Particularly relevant to CACs in Vancouver is the idea of “land lift”—the increase in land value that occurs when land is rezoned for higher density or other valuable uses. In Vancouver, this concept has become central to the Community Amenity Contributions (CAC) system, as the City captures a portion of this increased value for public benefits like infrastructure or affordable housing.

During the early stages of Vancouver’s development boom in the 1990s, when land was relatively inexpensive, Vancouver could capture a significant portion of this lift through CACs to fund public improvements and keep housing costs manageable. But as global markets started speculating on Vancouver real estate, land prices skyrocketed, often outpacing the benefits captured through Community Amenity Contributions.

By the 2010s, much of the land lift was “baked into” land prices before development negotiations began, reducing the City’s ability to claim a significant portion for the public good. Speculation and rising land values led to developers to claim that there was little “land lift” left to contribute. This dynamic weakened the effectiveness of CACs, making it increasingly unsustainable and ineffective. The effects are clearly in the graphic below.

This issue affects many of Vancouver’s housing strategies, including its Affordable Housing Strategy, which broadly aims to create a mix of rental, social, and co-op housing. But without clear definitions for affordable and social housing, as well as better control over land prices, these aspirations are largely ineffective. High demand, low supply, and exorbitant land costs keep housing out of reach for most.

A particularly troubling development is the City’s recent recommendation to reduce the social housing requirement from 25% to 20% in parts of the West End, allowing developers to “buy out” of this obligation by making cash contributions to the City instead. This cash-in-lieu option lacks any real timeline or assurance for delivering affordable units off-site. It reflects a market-first mentality that further erodes affordable housing efforts.

Vancouver’s attempts to cap rent increases and prevent renovictions have also fallen short due to weak regulatory frameworks. Compare this with Barcelona’s strict rent regulations and tenant registry, which make renovictions almost impossible.

Strengthening tenant protections and implementing broader rent controls are essential steps Vancouver must take to provide housing stability. Here again we see the creation of inept policies like the Broadway Plan and the Province’s Transit-Oriented Area regulations spurring the demolition of affordable mature rental and eviction of tenants under the guise of providing more affordable housing.

Worth noting is the City’s intentional denial to collect the necessary information on demovictions. Such regulatory behaviour is inconceivable within Barcelona’s people-first framework with its clear monitoring and evaluation Metropolitan Housing Observatory (O-HB) system.

Moreover, Barcelona repurposes vacant properties to increase affordable housing, imposing fines on owners who leave properties vacant. Incentives are offered to rent out empty units, and unused buildings are converted into affordable housing. Vancouver could benefit from adopting similar measures, such aggressive financial penalties for underuse and incentives for renting out vacant units.

Vancouver’s Empty Homes Tax, introduced in 2017, has had some success in reducing vacant properties and generating revenue for affordable housing projects. But high land and construction costs remain major barriers to creating truly affordable housing.

Barcelona also excels in three key areas where Vancouver lags. First, Barcelona’s Metropolitan Housing Observatory (O-HB) tracks housing demand, supply, and trends, enabling better policy adjustments. Vancouver, by contrast, lacks complete data, leading to ineffective policy responses. The City’s refusal to collect information on tenant evictions related Broadway Plan is wroth mentioning here again.

Second, Barcelona’s public-private partnerships, such as Habitatge Metropolis Barcelona—a mixed-economy development company-owned 25% Barcelona City Council, 25% AMB, 50% private developers (NEINOR and CEVASA) selected through public procurement. This public-private collaboration significantly boosts affordable housing supply but such partnerships do not exist in a similar form in Vancouver,

Lastly, Barcelona’s affordability requirements for Affordability Requirements in Green Fields and Brown Fields requires developers to allocate 40% of land as Officially Protected Housing (HPO), with half of these units designated for rental. Moreover, the municipality receives 10% of all development rights for free. Due to the lower value of land zoned for affordable housing compared to market housing, the municipality often ends up with 20% to 25% of the land that is used towards the creation of new affordable housing leveraging their public-private partnerships. This is over and above the required 30% Measure.

Barcelona’s model shows that public investment and municipal involvement are crucial for accelerating the construction of affordable housing. But what sets Barcelona apart is its political will and vision. Leaders like Ada Colau, driven by a people-first mentality, have successfully created one of the most innovative housing systems in the world. In contrast, Vancouver’s leadership has continued to place faith in market-driven solutions, despite evidence that they aren’t working.

Barcelona’s openness to sharing its experience—including with foreign visitors like us—further highlights the spirit of collaboration that is key to solving global housing challenges. They admit their system isn’t perfect, but they have adapted global best practices to suit their local context. Vancouver, however, remains blind to the contradictions in its approach.

It is worth mentioning at this point that Vancouver does have a history of people-first planning, particularly in the 1970s, before attempting its market-based planning focus. This period saw the creation False Creek South—North America’s most studied and enduring intentional community. We will revisit this in the final piece of the Barcelona Chronicles.

However, now that we’ve covered the policy landscape, let’s move on to the physical environment and see how the citizens-first mentality has affected Barcelona’s urban design, with a closer look at the Superilla initiative…

***

Other pieces in the Barcelona Chronicles:

- Part 1 – Introduction

- Part 2 – Cerdà and Colau: Two Key Figures

- Part 3 – The Barcelona Housing Policy 2015-2023 Overview

- Part 4 – Defining Affordable & Social Housing

- Part 5 – Supplying Affordable Housing

- Part 6 – The 30% Measure and Others

- Part 7 – Vancouver v. Barcelona – Foundations

- Part 9 – The Eixample and the Superilla

- Part 10 – The Superilla Pilot

- Part 11 – The Superilla…Evolved

- Part 12 – Vancouver v. Barcelona – Urban Design

- Part 13 – Reflections on Two Cities

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.