Authors: Pablo Sendra and Richard Sennet (Verso, 2020)

Pablo Sendra and Richard Sennet are established professors and urbanists who have significantly contributed to architecture, planning, sociology, and others throughout their careers. Designing Disorder is a follow-up book to Sennet’s 1970 title Uses of Disorder. This new book serves to revisit some of its themes in the form of a three-act play where Sennet sets the stage, Sendra builds the conflict, explores “Disorder” through place-making. It comes together and the end when the authors are interviewed together.

The book is about boosting social interactions in cities by making room for chance encounters. It argues that when cities make things like power and water systems more accessible—things we usually don’t see or think about—it can help increase activity. It also gives examples of how cities can encourage the kind of interactions we all want, without just falling back on the usual excuses for why they don’t.

Designing Disorder begins with some vocabulary building. “Disorder”, for example, is spontaneity enabled and describes what happens when people interact more fully and freely with their city. It is also only possible in the “open city.” The “open” and “closed city” refer to how infrastructure is managed. Cities are commonly “closed,” meaning their infrastructure systems are inaccessible and managed by municipal staff and experts.

By contrast, an “open city” is where infrastructure is accessible and useable by more people. This could mean having additional water and electrical outlets in public places for general use or creating lighting and sound systems integrated into the streetscape and designed to enable different events, markets, or other uses.

Sendra and Sennet argue that accommodating Disorder is an orderly process. However, it requires those traditionally responsible for managing public spaces and infrastructure to relinquish some control. The authors refer to these systems—electrical, water, and other utilities—as the “technical floor” of a public space. By opening the “technical floor”, cities can enable broader activities. Public spaces with greater densities of open infrastructure have greater possibilities for activity. The book contains examples like Gillet Square in London, La Candelaria in Bogota, or the Buskenblaserstraat in Amsterdam.

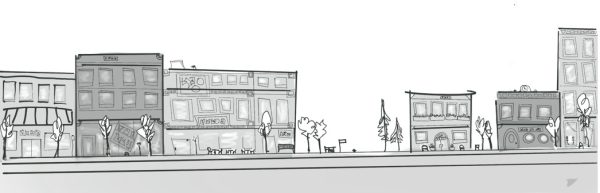

The book also offers suggestions for examining any urban spaces in cross-section—or “section”—to understand how they can be activated and what systems can be made accessible. Sendra states that longitudinal sections communicate the narrative of place by exposing transitions between private, semi-private, and public spaces through barriers, fences, buildings, and pathways.

The illustration below shows a city street in a longitudinal section that is open to interpretation. The street is lined with private buildings and public amenities on the street, but semi-private space between buildings and cafe spaces that invite, but remain for commercial purposes. A large public park in the middle is meant to show another transition, while the smaller park may be private.

In contrast, transverse cross-sections communicate more about the connections within a space and can tell us more about ownership, transportation modes, and vertical connections. These more detailed views bring us closer to the experience of a particular place.

The illustration below shows a city street in a half cross section that is open to interpretation. On the left, a private building stands as a firm wall to the public realm, but it is softened by cafe seating. The street has dedicated space for pedestrians, cyclists and vehicles. The sidewalk is clear, save for utilities, a post box and various regulatory signage. Above, street lights and electrical wires connect buildings and a trolley bus, while cellular infrastructure hums above.

Sendra also encourages city builders to find places where people already congregate and have a sense of ownership over the space. This makes it easier to intervene: working to amplify the latter by offering infrastructure that can be owned or managed locally to encourage stewardship and activity.

Designing Disorder closes with an interview with the authors, in which the ideas discussed throughout the book flow and take on new life. In it, they make their most salient points. Sennet asserts that Disorder is important currently, observing that life has become more complex, and people feel less competent in contributing or making a difference. Democratizing infrastructure is a way to reintroduce agency. Similarly, Sendra points out that density does not equal Disorder. The compression of people in smaller areas does not bring life to a city. Instead, spaces must be intentional in their purpose to foster bumping and mixing.

If the goal is to democratize and design open systems in the city, then there are three approaches every city builder should take to heart to create Disorder:

- Train people to accept the unknown.

- Loosen restrictions.

- Leave things unfinished.

Designing flexibility into urban spaces invites people, businesses and future planners to modify and experiment with place. Purposefully saving space for the unknown is key to encouraging the kind of interactions and experiences we all want from the places we live.

***

For more information on Designing Disorder: Experiments and Disruptions in the City, visit the Verso website.

**

Andrew Cuthbert is a community planner who works in great places all over British Columbia. He loves helping to solve complex problems. When not working, Andrew can most likely be found on his bike taking in the sights and fresh air.