In 2024, Ontario Premier Doug Ford ordered the removal of bike lanes from some of Toronto’s busiest corridors—Bloor, University, and Yonge—claiming they contributed to traffic congestion. His decision contradicted decades of research demonstrating that thoughtfully integrated cycling infrastructure improves traffic flow, enhances safety, and expands mobility for all road users. Meanwhile, in New York, Mayor Eric Adams cut funding for the city’s Open Streets and pedestrian programs, despite compelling evidence from planners and transportation experts highlighting their value for safety, equity, and urban vitality.

These are not isolated missteps. They point to a deeper, more enduring paradox: the individuals making the most consequential decisions about our cities often have the least formal understanding of how cities actually function. Mayors and councillors are routinely elected from backgrounds in law, business, communications, or activism—fields that bring valuable skills but rarely provide the knowledge required to steward one of the most complex systems humans have ever built.

Does this gap matter? And if so, what are its consequences—and what can be done about it?

Cities are ecosystems of extraordinary complexity. They are shaped by—and exert pressure on—interconnected systems of transportation, architecture, ecology, housing, governance, and culture. They are not static entities but dynamic, evolving organisms that demand fluency in a wide array of disciplines: zoning and design, infrastructure and engineering, environmental stewardship, social justice, and economic planning, to name just a few. Each of these domains carries its own knowledge base, historical baggage, and theoretical debates. Yet most city leaders receive no formal training in any of them.

At best, political leaders are selected for their ability to articulate a compelling vision, manage relationships, or mobilize voters. These are vital democratic capacities—but they do not guarantee sound governance. Too often, decisions are made through the lens of electoral timelines, optics, and short-term pressures rather than a long-term, systems-based understanding of the city.

The history of freeway construction in North America offers a cautionary tale. Despite overwhelming evidence that expanding road capacity leads to more congestion—a phenomenon known as induced demand—governments continue to invest in highway expansion because it remains politically legible, shovel-ready, and photogenic. It looks like progress. But it rarely is.

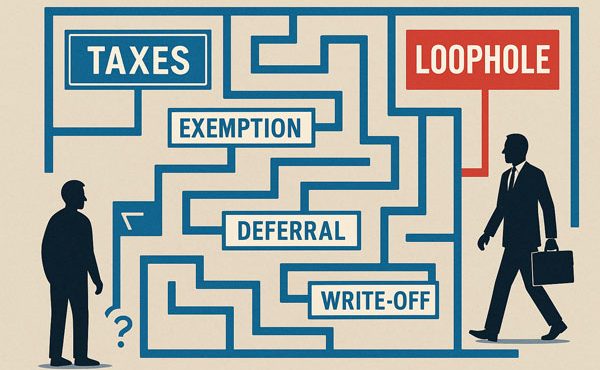

Today, housing has replaced highways as the dominant urban battleground—and familiar patterns are repeating. Politicians invoke urgency, sidestep nuance, and oversimplify complex social and economic dynamics to serve narrowly defined interests. Where the promise was once “mobility” through asphalt, it is now “affordability” through deregulation. In both cases, legitimate public concerns are funneled into political narratives that often serve donors, developers, and entrenched power structures.

One might imagine that, faced with such complexity, cities would lean heavily on expert advisors—urban planners, economists, environmental scientists, engineers and others. And to some extent, they do. But their influence is often precarious. While experts can draft policies and provide analysis, final decisions rest with elected officials whose motivations frequently diverge from evidence-based practice. Short-term public opinion, ideological agendas, and campaign pressures routinely override the slower, more deliberative process of informed governance.

In city after city, planners advocate for things like improved transit, walkable neighbourhoods, mixed-use zoning, and robust social infrastructure. Yet these recommendations are often shelved, diluted, or outright rejected by leaders catering to car-centric or anti-density constituencies. A similar pattern unfolds in zoning reform, where public consultations are weaponized, and expert input is overridden to protect vested interests.

This recurring pattern raises a thorny questions: are we drifting toward technocracy, where unelected experts wield too much influence? Or is the real danger something quieter—and perhaps more insidious—a political class entrusted with the future of our cities, yet fundamentally untrained in the systems they govern?

At the heart of this dilemma lies a broader societal contradiction: we demand expertise in almost every sphere of public life—medicine, engineering, education, law—yet we make one of society’s most technically complex roles accessible to anyone, regardless of background or training. We would not allow a self-taught architect to design a bridge or an unlicensed doctor to perform surgery. And yet, we routinely elect people to shape our cities—places where millions live, work, and move—who may never have studied how cities actually function.

Globally, not all cities operate this way. In parts of Europe, urban literacy is more deeply embedded in governance. Paris, under Mayor Anne Hidalgo, has enacted bold pedestrian and cycling reforms, supported by a team of highly knowledgeable planners. In contrast, many North American cities are governed by generalists—well-intentioned, perhaps, but often unfamiliar with the mechanics of urban systems beyond the political arena.

Some municipalities have adopted a hybrid model, where city managers with technical backgrounds oversee daily operations, while elected officials provide broader policy direction. In theory, this balances technical expertise with democratic accountability. In practice, the balance is fragile. City managers may lack the political mandate to implement bold reforms—or, as Vancouver’s experience shows, may use their authority to advance private interests over the public good.

The tenure of former Vancouver City Manager Penny Ballem illustrates the risk of unchecked administrative authority closely aligned with development interests. Appointed without a public search process, Ballem oversaw a period marked by the quiet departure of pro-community planning staff and an increasingly top-down decision-making culture. Post-tenure accounts describe a pattern of micromanagement and prioritization of developer relationships over the public interest. Ironically, her appointment followed criticism that her predecessor wielded too much power—only for that power to be further concentrated and exercised with even less transparency.

These dynamics are intensified in “strong mayor” systems, which are becoming increasingly common in Canada and the United States. While such systems can expedite decision-making, they also concentrate authority on individuals who may lack even a basic understanding of urban policy. As more cities adopt these models, the stakes rise: what kinds of decisions are made when decision-makers don’t understand the systems they are altering?

The problem is not only who we elect, but how we elect them. Contemporary campaigns often reward charisma over competence, and rhetoric over rigour. Platform language is deliberately vague—“affordability,” “public safety,” “vibrant communities.” These terms poll well but obscure the complex, contested, and technical realities they claim to address. Everyone wants safer streets and affordable housing—but the methods to achieve those goals vary dramatically. Without civic literacy and media transparency, voters are left guessing what these promises mean in practice.

Even when expert input is solicited, the process is often compromised. Advisory panels are stacked with individuals aligned with the governing agenda. The appearance of consultation conceals the absence of genuine dissent. British Columbia’s recent housing mandates, for example, leaned heavily on development-aligned advisors while sidelining independent urbanists, architects, planners and housing researchers. The close relationship between the Urban Development Institute and provincial housing policy is well documented. Meanwhile, respected experts across disciplines continue to be ignored or dismissed.

This is the hidden architecture of political inertia: decisions made without expertise, legitimized through performative consultation, and shielded from accountability by the very systems that enable them. As long as no laws are broken, poor decision-making carries no consequences—only delayed impacts. And by the time those impacts surface, the architects of those decisions are often long gone.

Mayor Ken Sim once remarked, “When you have more than one person or one group accountable for anything, no one’s accountable.” In theory, this is a call for clarity. In practice, it conceals a deeper truth: even when authority is consolidated, accountability can remain elusive—especially in municipal governance, where long-term consequences stretch far beyond political terms.

The knowledge gap in urban governance is not an abstract concern. It shapes the built environment, the cost of living, the accessibility of transit, the livability of neighbourhoods, and the possibility of equitable, sustainable futures. What’s at stake is not just efficiency—but democracy itself. When decisions are made in ignorance, cloaked in the language of public interest, and insulated from meaningful scrutiny, democracy is weakened—not by too much expertise, but by too little.

Can cities afford to be led by people who do not understand them?

This brings us to the crux of the issue. Many understandably recoil at the idea that only those with formal training should hold office. It sounds exclusionary and risks turning democratic leadership into a gated profession. It evokes technocracy—power concentrated in the hands of experts who may be disconnected from public values and lived experience.

There is a deeply held belief that elected office should be open to anyone—that it is the representative’s job to represent the public will, not necessarily to “know.” Under this classic model, the mayor or councillor provides the democratic input, while civil servants offer the technical output.

But cities today are not what they were even a century ago. They are complex, technical environments. A modern mayor makes decisions about emissions targets, land use, climate adaptation, mobility systems, digital infrastructure, and housing economics—with long-term, often irreversible consequences.

And here’s the key: we already value expertise in every other domain that involves high-stakes, systemic complexity.

We would never let someone without training fly a commercial plane or trust a courtroom to someone who’s never studied the law. Yet we routinely elect leaders to make decisions about the systems we live within—housing, transportation, energy—without requiring even a basic understanding of how those systems work.

That’s not an argument for excluding people from politics. It’s a call to raise the baseline of what we expect from leadership.

Not everyone who runs for office needs to be an urban planner or housing economist. But they should be urban literate. They should be able to ask the right questions, recognize when staff recommendations are being politicized, challenge lobbyists, and govern with long-term consequences in mind.

The more technical and interconnected our challenges become—climate, housing, mobility—the more dangerous it becomes to equate “being electable” with “being equipped to govern.” We don’t need to replace democracy with expertise. We need democratic leadership that understands and respects expertise. And within that context, it’s crucial to acknowledge that communities bring their own forms of lived expertise.

This is not an argument for exclusion—far from it. It is a call to recognize that we have underbuilt the infrastructure of civic competence. If anything, it is a more democratic argument: that voters deserve the tools to make informed choices; that leaders should be trained, not just elected; and that cities—our most intricate, collective creations—deserve governance that reflects their complexity.

We need to build a robust foundation of civic competence—an infrastructure that supports urban literacy among elected officials, civil servants, and the public alike.

Voters can and should demand more specificity, transparency, and urban literacy from their leaders. Ideally, they should assess the backgrounds of candidates with an eye toward their knowledge of urban systems. Post-election training in urban systems should become standard. (Vancouver once offered such training to city staff and councillors—until it was eliminated under Ballem’s leadership.)

Participatory frameworks must also be reimagined to prioritize evidence, inclusion, and long-term vision over expediency and optics. This is not far-fetched. Governance systems are designed. If the ones we have no longer serve the common good, they can—and must—be redesigned.

In the end, cities are not merely shaped by concrete and policy. They are shaped by who we empower to lead them—and by what those leaders are empowered to know.

***

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.

One comment

What are cities? There is that famous phrase sometimes attributed to Claude Levy-Strauss, “Me make the city, then the city makes us.”

I have also felt many times, visiting many places, or just involved in my own work, that the city is the unconscious projection of the collective.

The difficulty here is with coming to terms with ‘all and everyone’ that is included in that ‘collective,’ from the most ardent activist to the greediest financier.

Freud opened “Civilization and Its Discontents” with his own rumination about Roma as an analogue for the human psyche. It strikes me to this day as a comparison in perfect balance: the city is best explained in reference to the functioning of a human being, the functioning of a human being in reference to a city.

In what is the longest, continuously inhabited urban footprint in the west, the famed Vienna psychoanalyst invites the narration about the many periods of progress and decline suffered by the ancient capital. The Noli map (1736 – 1748) freeze-frames the culmination of one of the metropolis’s busiest periods: the time the Renaissance and Baroque Popes took over.

Yet, alongside these ruminations of progress, we become aware of the many times the city was laid waste, or the long periods it lay in ruins, barely functioning.

So while I experience cities with a great sense of immediacy, and worry about civic policy and the damage being wrought daily, I have that other place to go: Roma. A city that teaches us that no matter how much we screw something up, urbanism will always bounce back.

Now, fair warning… it may take centuries.