The Coriolis Effect, Part I went through a long gestation period as I humbly asked various people within the discipline for constructive feedback. I was grateful to receive generous, well-argued critiques from well-seasoned planners and others with decades of experience.

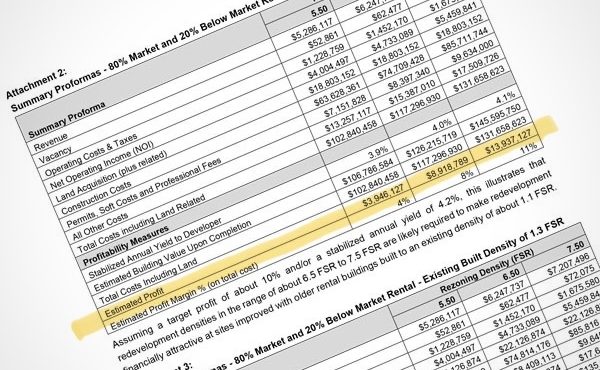

Although many praised the clarity of the writing and overall message, some took issue with what they saw as a misfire in my target: the humble pro forma. It’s just arithmetic, they reminded me—a basic spreadsheet developers use to test feasibility, no more villainous than the tools used to grow tomatoes.

They’re right… at least partly right.

At its core, the pro forma is a financial model. And although Part I argued that its impersonal “objectivity” masks deep bias and oversimplifies the world, it is not inherently evil—or even particularly clever. It calculates whether a project “pencils out.”

As several constructive critics pointed out, planners have long used pro formas to test market responses, gauge development potential, and help set public value capture rates. In that sense, it’s no different than a balance sheet or a farm yield forecast. So let me be clear: the pro forma isn’t necessarily the problem, despite its flaws.

The problem is that in too many planning offices and municipalities today, the pro forma has stopped being a reference point and has become the compass.

What was once an input is now the decider.

We aren’t just asking, “Can this be done?” but “Should this be done?”—and we’re answering that question with a spreadsheet. That shift, subtle as it may seem, has enormous consequences. It’s something award-winning journalist Frances Bula captures well in her recent article on the Broadway Plan in BC Business and her interview on the Vancouver Real Estate Podcast.

The planner’s role was never meant to mimic the developer’s. The planner works in public service, not private risk management. Their job isn’t to optimize returns but to ask whether the city being built serves those who live in it—and those who don’t yet but might, if we plan wisely. The best planners see the pro forma not as a guide but as a test. And sometimes, that test tells us: this doesn’t work—not if we want trees, daylight, dignity.

One planner I spoke with shared a story: years ago, a developer wanted to cut down a mature tree to make way for an underground parking garage. The planner insisted that the wall of the garage be bent to preserve the tree. The developer showed the pro forma and how saving the tree negatively affected the bottom line. The planner didn’t back down—the tree would stay, or the building wouldn’t be approved. The garage was built with a bend, and the tree still stands.

That story isn’t anti–pro forma. It’s anti–deference. It’s a reminder that planners are meant to push, not simply to permit.

What’s changed isn’t the tool but the ideology.

A generation ago, a planner might say, “If the numbers don’t work, sell your land.” Today, a planner might say, “How can we make the numbers work?” And if they don’t, someone at City Hall might label them anti-housing, or worse yet, anti-affordable housing. The courage to say no—to reroute the machinery of growth when it veers off course—has been systematically eroded. A culture of fear has filled the void.

This brings me back to the original point of The Coriolis Effect, Part I. The critique wasn’t only partially about the spreadsheet. More importantly, it was about how certain consulting firms—and the cultural conditions that empower them—wield these tools to subtly, but consistently, steer urban planning toward the interests of capital.

This isn’t a conspiracy; it’s a gravitational pull. But like the Coriolis force itself, it changes trajectories without ever appearing to exert force at all.

To be clear, this isn’t a blanket condemnation of consultants. Many do valuable, principled work, often for government clients seeking to calculate land lift, determine value capture, or model development scenarios. In fact, firms like Coriolis have provided vital technical support to cities, including work that helps governments get public benefit from private gain.

The issue, then, lies not just in the tool or the consultant, but in the political and institutional culture that commissions and interprets the work.

In the case of the Broadway Plan, for example, Coriolis was asked to show how much density would be needed to rebuild neighbourhoods into high-rise corridors. That’s what they delivered. But planners could have asked a different question: How do we protect existing affordable rental housing while increasing density near transit? The resulting model would have looked very different.

This is where planner agency matters.

Consultants build to spec. If the spec is defined narrowly by market logic—or by a council too afraid to challenge it—the outcome isn’t evil, but inevitable. What’s missing isn’t better math. It’s a better mandate.

And yet, the danger isn’t just in the brief—it’s in the blind trust. As several experienced planners reminded me, pro formas—like transportation studies and retail impact models—can be easily tweaked to serve a goal. Variables can be nudged. Risk profiles adjusted. Appraisals redone until the project “works.” In many cases, these tweaks are perfectly justifiable. But sometimes, they’re not. And when planners lack the fluency or confidence to challenge these assumptions, they become vulnerable, not to consultants, but to capture.

This is the deeper issue. The tools we use aren’t just technical—they’re ideological. They reflect what we measure, what we ignore, and whom we’re ultimately planning for. Pro formas aren’t villains. But when planners outsource public judgment to private math, they become complicit in reshaping the city around profitability instead of possibility.

The pro forma may be arithmetic. But what we do with it…well, that’s politics.

***

The Coriolis Effect Series:

- The Coriolis Effect, Part I: Planning by Spreadsheet

- The Coriolis Effect, Part II: Beyond the Spreadsheet

- The Coriolis Effect, Part III: Reclaiming the Planner’s Toolkit

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.