In the 1960s, planning decisions in Vancouver—like many North American cities—were made behind closed doors. Freeways bulldozed working-class neighbourhoods. “Urban renewal” was synonymous with demolition. Public input wasn’t sought; it was treated as an impediment.

But Vancouver residents pushed back. They stopped a planned freeway, saved Strathcona, and gradually reoriented the city’s planning culture around community participation. Imperfect, yes—but built on the belief that people should help shape the places they live.

Today, that hard-won civic footing is quietly being dismantled—undone by a new era of centralized planning driven not just by provincial fiat, but by coordinated lobbying efforts from the development industry.

On June 3, 2025, Vancouver City Council passed the Development Approval Procedure (DAP) Bylaw—one of the most consequential planning changes in recent history. Released just three business days before the vote, it appeared procedural, even dull. But beneath the surface, it accelerated a provincial effort to shift power upward, away from communities and into the hands of provincial ministries and unelected staff.

This is not just a technical update. It’s a democratic transformation—one happening largely out of public view.

The reforms present themselves as efforts to “modernize” an outdated system. In reality, they rely on a trifecta of control:

- Stealth — New policies, like the DAP bylaw, are introduced quietly, often just days before decisions are made.

- Speed — Compressed timelines limit the public’s ability to learn, respond, or mobilize.

- Complexity — Dense legal language masks the stakes, making it hard for ordinary residents to understand what’s changing.

Together, these tactics disorient and preempt. They also tend to unfold in a distinct order. First, you don’t hear about the change: new policies are introduced quietly, often buried in procedural language or released with little notice. Then they’re passed before the public can even react. And when residents finally do try to engage, they’re met with dense technical jargon that cloaks the stakes in ambiguity and administrative fog.

As we will see, this trifecta applies not just to local changes like the DAP—it is embedded in the very structure and passage of the provincial directives themselves.

The Development Approval Procedure bylaw, however, exemplifies all three. Although framed as a compliance measure, it significantly limits when public hearings are required (stealth), shifts decision-making to staff (speed), and formalizes a planning regime where efficiency takes precedence over dialogue (complexity).

We’ve seen versions of this before. Jane Jacobs warned against governments imposing rigid order on city life. True livability, she argued, comes from the bottom up—from neighbourhood knowledge, human interactions, and informal networks. When that vitality is flattened by centralized authority, cities don’t just lose their charm. They lose their democratic soul.

This quiet dismantling of transparency is not incidental—it’s foundational to how urgency is now being wielded.

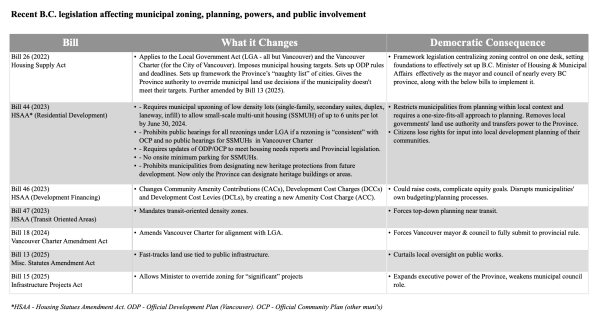

Since 2022, the Province has enacted a cascade of top-down legislative directives. That year, the Bill 43 (Housing Supply Act) set up the framework for imposing housing targets on municipalities—creating a “naughty list” of defiant cities—and a schedule for adopting official community plans and the prohibition of public hearings

In 2023, Bill 44 (Housing Statutes Amendments Act – Residential Development) mandated upzoning for multi-unit housing on formerly single-family lots, and Bill 47 (Housing Statutes Amendments Act – Transit-Oriented Development) for towers of 8 to 20 storeys for 800 metres in Transit Oriented Areas around stations. In 2024, the Vancouver Charter was further changed under Bill 18 (Vancouver Charter Amendment Act) for Official Development Plans.

The DAP bylaw removes public hearings for rezonings aligned with Official Development Plans as required under Bill 18. Council also loses its final say on project design; that authority will now rest with City staff—likely effective this month. These directives compress timelines (speed) and narrow public visibility (stealth), while enshrining procedural barriers to comprehension (complexity).

A detailed summary of the key legislation—Bills 26, 44, 46, 47, 13, 15, and 18—underscores how each bill, in its own way, contributes to this centralized realignment of planning authority. A reference table outlining these changes and their democratic consequences is included at the end of this article.

On paper, the process still looks participatory. In practice, it’s a closed loop—directives flow from the Province to staff, bypassing the civic forums where conflict, consensus, and public input once lived.

This isn’t just a shift in governance mechanics. It’s a shift in values. Whose voice counts? Who gets to shape the city’s future?

The Development Approval Procedure bylaw’s passage reveals how quickly this transformation can happen. The document was released on Thursday, May 29. The deadline to sign up to speak at Council: 5 p.m. on Monday, June 2. The vote occurred the next afternoon. One of the most consequential planning changes in recent memory passed in only three business days—with no meaningful public debate. Stealth. Speed. Complexity.

And it’s not the first time.

In April 2022, then-Housing Minister David Eby met privately with the Urban Development Institute, a major developer lobby. The meeting—titled “Hong Kong Model, Transit Density”—was revealed through a Freedom of Information request. Within 24 hours, Cabinet drafted a concept paper: Provincial Intervention in Local Zoning to Allow More Homes. The language of Bills 44, 46, 47 & 18 closely mirrors UDI proposals, suggesting this wasn’t a crisis response, but a coordinated strategy.

While some praised these bills for addressing exclusionary zoning, their origins raise difficult questions: Whose interests shaped the law? And who was excluded from the conversation?

Industry lobbyists have painted community members as selfish obstructionists. But this narrative conceals its own self-interest: by framing public input as a nuisance, the development industry seeks to eliminate anything that might slow or challenge its profit-driven agenda.

Planning in Vancouver has always balanced competing pressures—growth and preservation, speed and scrutiny, private interest and public good. These reforms upend that balance.

The DAP bylaw makes this explicit. If a rezoning checks the right boxes—mostly residential, aligned with an existing plan—the public no longer has a statutory right to be heard. Proposals that fall outside those bounds may proceed through internal pre-application meetings without wider civic engagement.

For tenants, advocates, and everyday residents, that means fewer access points, less transparency, and a growing sense of disconnection from the decisions that shape their lives.

Yes, notifications are still issued. But what is a notification without the right to influence?

Worse still, even the public notice requirements—once a minimal safeguard of transparency—have been quietly weakened. The DAP bylaw makes opaque references to the Vancouver Charter but omits the actual section numbers that define public notice obligations. The result is strategic ambiguity: it’s now harder for residents to know when, how, or even if notice will be posted.

Section 6.2 of the bylaw uses discretionary language—staff “may” post signage—meaning that in many cases, public notification becomes optional, entirely at the whim of the Director of Planning. This isn’t just bureaucratic oversight. It’s complexity deployed with intent.

Supporters argue that the reforms are necessary to solve the housing crisis. And urgency is real. But urgency cannot justify secrecy.

Even the Union of BC Municipalities (UBCM)has raised the alarm: the Housing Supply Act enables the Province to override local planning authority through ministerial orders, appointed advisors, and bylaw interventions. Yet this warning came late, well after the legislation was passed and implemented. And that delay is telling.

The trifecta of stealth, speed, and complexity doesn’t just bypass residents—it outpaces the very institutions meant to defend them. Caught flat-footed by wave after wave of legislation, even UBCM has been reduced to reacting after the fact, once the damage is already done.

And they are not alone. Most media outlets and advocacy organizations have struggled to respond in a timely manner—sometimes due to institutional sluggishness, but often because they are constrained by non-disclosure agreements or advisory roles that prevent them from speaking out. These are not just communication failures; they are features of a system designed to stay ahead of scrutiny.

Their recent analysis notes that developers could exploit this top-down pressure to bypass community amenities, and that municipalities, under fear of intervention, may fast-track projects without due diligence or consultation. But urgency cannot justify secrecy. Efficiency does not excuse exclusion.

The belief that more market supply alone will deliver affordability has long been challenged by housing scholars. Without requirements for non-market housing and without integrated plans for schools, transit, and infrastructure, we risk building faster but not more fairly. Cities risk becoming pipelines for capital, rather than homes for people.

Even the justification for speed rings hollow. Across Metro Vancouver, tens of thousands of development approvals are already on the books—waiting, not on permits, but on market conditions. In Surrey alone, over 44,000 approved units sit unbuilt; Burnaby has another 25,000, according to Burnaby Mayor Mike Hurley. These are not being delayed by red tape. They are being held back by developers watching the market, waiting to maximize return.

Worse, we risk cultivating a governance culture that prizes delivery over deliberation—treating the messiness of democracy not as a value to protect, but a problem to solve.

British Columbia has long championed participatory planning. But the democratic process isn’t self-sustaining. It requires vigilance, culture, and habit.

Vancouver’s Development Approval Procedure bylaw—and the broader reforms around it—signal more than just a new policy direction. They reflect a new vision of governance, where public trust is seen not as a foundation to build on, but a bottleneck to remove.

The question isn’t just “how do we build more housing?” It’s “who decides what gets built, where, and for whom?” And just as urgently: “What happens when the public is no longer invited to answer that question?”

The window to speak on the DAP bylaw closed before many even knew it existed. That fact alone should raise alarms.

There’s still time—but not much.

This is not just about planning. It’s about power. When process is shortened (speed), language obscured (complexity), and public voice sidelined (stealth), democracy itself is under renovation—without permits, without plans, and without the people.

We need housing. We need speed. But we also need memory, accountability, and care. The future of our cities should not be decided in silence—not by design, not by default, and definitely not by those who fear the sound of a collective voice.

***

Below is a summary table of the recent B.C. legislation affecting municipal zoning, planning powers, and public involvement.

**

Related Spacing Vancouver pieces:

- Trifecta of Control

- Entitled to Flip

- When Care Becomes Control

- The Slow Emergency

- The Broadway Plan Blues

- Learning from Moses

*

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.

One comment

Can you imagine the horror, homes might be built!