In Vancouver today, rezoning doesn’t necessarily mean building. Increasingly, it means something else: securing entitlements — legal permissions that inflate a property’s value regardless of whether anything is actually constructed. Nowhere is this clearer than at 1780 East Broadway, the high-profile Safeway redevelopment at Commercial-Broadway Station.

At first glance, the proposal is a win: three towers, a thousand new rental homes, and a redeveloped grocery store at a major transit hub.

But this site isn’t just another parcel of land slated for redevelopment. For decades, the Safeway at 1780 East Broadway served as a vital community hub—both functionally and symbolically. In 2015, it was at the centre of one of Vancouver’s most ambitious participatory planning efforts: the Grandview-Woodland Citizens’ Assembly. This citizen-led body was formed in response to community backlash against early proposals for high-rise towers at the site. After months of deliberation, the Assembly endorsed a modest development plan: mid-rise buildings, a public plaza, and a pedestrian-oriented retail precinct.

City Council’s 2016 Grandview-Woodland Plan adopted many of these recommendations, suggesting building heights between 12 and 24 storeys and designating the site as a “community heart.” Yet what was approved in 2025—three towers reaching up to 44 storeys—is a dramatic departure from that original vision. What began as a landmark experiment in community-based planning has become a case study in how public engagement can be overridden by speculative ambition.

But listen to the developer’s own words. During a November 2024 investor call, Crombie REIT CEO Mark Holly stated plainly:

“It is a JV [joint venture] with Westbank…We are optimistic that sometime in the first half of 2025 we will have that fully entitled… Once we get to that point we are going to review our options. Which will include a monetization of that asset.”

This isn’t a side note—it’s the business model. It reveals a broader truth behind this and many similar rezonings under the Broadway Plan: these aren’t necessarily about delivering homes. They’re about manufacturing tradable rights—a kind of paper gold—that can be held, leveraged, or flipped for profit.

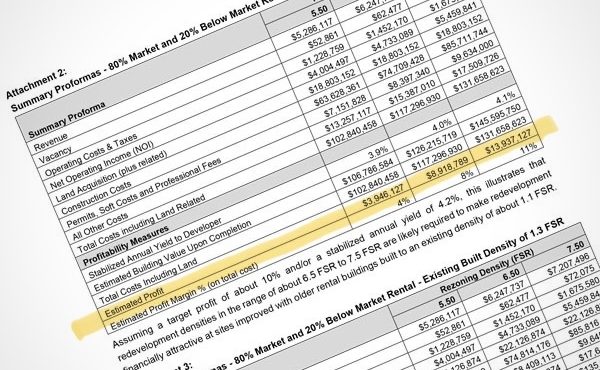

The rezoning journey for this site has taken years. Since 2019, the proposal has grown in height and shifted in focus—from a mix of strata and rental units with a floor space ratio (FSR) of 5.53, to a 100% rental plan with more than 1,000 units. The approved rezoning includes an FSR of 8.3 and a building height of 479 feet, described as 44 storeys—though with amenity levels, the number could climb to 47.

Yet only 10% of the units will be rented at “average citywide rents”—a benchmark that doesn’t even meet basic affordability standards. The project lacks the 20% below-market housing component typically required under city policy.

To permit this level of development, the City approved an FSR increase of 2.6 over the Grandview-Woodland Plan’s original guideline (8.3 vs. 5.7), translating to approximately 274,800 additional buildable square feet—worth an estimated $40 million at $150 per buildable square foot. This windfall was granted with no guaranteed community benefit. On paper, the project aligns with housing goals. In reality, it’s more about maximizing marketable entitlement than delivering urgently needed housing.

Entitlements have real monetary value. When Council approves a rezoning, land value rises—not because of any actual development, but due to the possibility of it. That speculative potential alone can justify massive gains for landowners.

As noted in the Trifecta of Control, many approved developments remain unbuilt—not because of permitting delays, but because developers are waiting for more favourable market conditions. Entitlement plays a central role in this dynamic.

According to the City of Surrey, over 44,000 approved units remain unbuilt, while Burnaby has another 25,000 stalled in a similar holding pattern. These units aren’t delayed by bureaucracy—they’re delayed by design, waiting to extract maximum value from market timing. Entitlements allow developers to hold land with increased financial leverage while deferring delivery indefinitely.

In fact, real estate investment trusts openly acknowledge this logic. Crombie REIT, in its 2024 Annual Report, notes that it calculates fair value for redevelopment properties in part based on “progress through entitlement.” Similarly, CAPREIT’s 2023 Annual Report describes how its development team works on “identification and entitlement” of underutilized land—entitlements that can then be sold off as shovel-ready assets. For them, entitlement isn’t a step toward housing—it’s a milestone of profit.

At 1780 East Broadway, all signs point to the site being sold before construction begins. And why not? With rezoning secured and no obligation to build promptly, the entitlement becomes the commodity.

As housing researchers Cameron Murray and Joshua Gordon argue, rezoning isn’t just a regulatory change—it’s a transfer of public property rights. Cities, by upzoning land, grant landowners access to more public space in the sky: in effect, they privatize public airspace.

“Land,” they remind us, is a bundle of socially constructed rights and permissions around height or density that belong, until rezoned, to the public. Without robust value-capture mechanisms, governments give away public assets for free, deepening inequality and failing to ensure more housing.

In this light, entitlements are not just financial instruments. They’re public gifts, repackaged as private property.

Architect and scholar Matthew Soules offers more insight into this process. In his work on the financialization of architecture, he describes how buildings have evolved into investment vehicles—optimized for capital rather than community. Building types like “ultra-thin towers” reflect financial logic more than urban design.

The Broadway towers follow this pattern. They are tall, narrow, and configured to maximize entitlement and exchange value—not human scale or livability. As Soules argues, such architecture distances itself from everyday urban life, turning buildings into abstract financial tools. What’s being constructed isn’t just housing—it’s vertical capital.

This isn’t merely speculative—it actively undermines the public good. Even when entitlements include obligations—such as affordability targets—the City has often watered them down in response to developer pushback. The CURV tower on Nelson Street, for instance, had its below-market commitments quietly reduced after approval.

The message: push hard enough, and you’ll get what you want.

This pattern also appears in city-initiated rezonings. At 520–590 West 29th Avenue, for example, staff declined to demand below-market housing, citing a 2018 rezoning that had already inflated land value, without securing community benefits. Entitlement inflation, in other words, cuts both ways.

Meanwhile, assessments based on “highest and best use” can drive up surrounding property taxes—not based on actual development, but on the hypothetical potential introduced by rezoning.

And now, developers are lobbying for protection from the tax consequences of their own entitlements. A June 2025 motion brought forward by Councillor Rebecca Bligh proposed a tax abatement scheme that would freeze property taxes at pre-rezoning levels for rental developments. Although the motion ultimately failed, it illustrates an ongoing push by some political actors to further protect entitlements and shield developers from the fiscal consequences of upzoning.

The rationale?

That rezoning-driven tax increases could deter construction. In effect, Council is being asked to create windfalls, then protect developers from the costs those windfalls create. It’s a burden shift that leaves the public footing the bill while reinforcing the notion that entitlement should be consequence-free.

From the BC Assessment perspective, the Safeway site will now likely be valued based on its approved future build-out—not its current grocery store use—raising assessments and, potentially, costs for nearby businesses and renters.

The 2025 rezoning wasn’t unanimously approved. Councillor Sean Orr voted against it, citing a lack of affordability. Councillor Pete Fry abstained—a procedural move that still counts as support but signaled discomfort. Public input was also significant: 619 written submissions opposed the project versus 459 in support, with over 140 people signing up to speak at Council.

Social media messaging from ABC Vancouver presented the project as a major win: “1,044 new rentals,” “on a transit hub,” and “with a childcare centre + plaza.” But critics were quick to challenge this framing. As Sean Orr put it, “double the height, no below-market rentals… not a plaza.” The cheapest projected units remain well above the neighbourhood’s median income, and no 20% below-market requirement was enforced.

At heart, this was never a vote on whether to build housing, but whether to continue letting speculation masquerade as public interest. Beneath the language of housing, the vote sanctioned something else entirely: the use of public power to manufacture private windfalls.

Nevertheless, the rezoning passed—demonstrating how entitlements are increasingly pushed forward in the name of supply, even when delivery remains uncertain.

Worse, once a rezoning is approved, the entitlement becomes legally entrenched. Reversing it—even in the public interest—would likely trigger costly legal action. Future councils are effectively bound by today’s speculative decisions. Entitlements become not just financial assets but political handcuffs.

Vancouver has previously used time limits to encourage developers to proceed. Some rezonings have included a two-year deadline for enactment or lapse of approval. This creates a time-sensitive boundary: if the developer fails to meet it, the approval expires. Enactment often requires substantial payments—such as Development Cost Charges (DCCs), Community Amenity Contributions (CACs), and bonding for in-kind amenities—demonstrating a serious intent to build.

However, developers have increasingly pushed to defer these obligations until after enactment or even after construction begins, replacing traditional financial guarantees with weaker alternatives. This trend dilutes the city’s leverage and further weakens incentives to actually build.

Once a rezoning is enacted, undoing it requires a full re-zoning—often a legal and political impossibility. Despite calls to mandate delivery timelines under the Broadway Plan, no such policies have been introduced to date.

Many now see the 1780 East Broadway approval as precedent-setting. With its record 44-storey height and just 10% of units priced at “average citywide rents,” it invites other developers to pursue similarly unbalanced projects. It risks normalizing a model of entitlement-first, delivery-later development.

As one city observer put it: Council believed it approved housing; in reality, it approved a financial instrument.

If Vancouver is serious about addressing its housing crisis, it must stop mistaking speculative entitlements for real solutions. Rezoning should be a path to building, not a shortcut to profit. Until City Hall closes the loopholes that allow speculation to masquerade as supply, the public will continue to lose.

Because in today’s market, you don’t need to build homes to make money—you just need to be entitled.

And entitlement, both in planning and in psychology, is a learned behaviour. Reward it, and it grows. Indulge it, and it metastasizes. Soon, you’re not regulating development—you’re appeasing it.

Vancouver has cultivated a development culture that expects approvals without obligations, density without delivery, and public decisions that function like private allowances. When challenged, the response isn’t accountability—it’s a tantrum, often backed by lawyers.

This isn’t just poor governance. It’s negligent parenting.

If the city doesn’t start enforcing limits, the tantrums will only grow louder—and public trust will continue to erode.

***

Related Spacing Vancouver pieces:

- The Slow Emergency

- Trifecta of Control: Stealth. Speed. Compexity

- Entitled to Flip

- When Local Planning Becomes Provincial Command

- The Coriolis Effect (3 part series)

- When Care Becomes Control

- The Broadway Plan Blues

- Learning from Moses

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.

17 comments

Superb !!!

Didn’t Vancouver have at one time, a mechanism to capture the windfall from re-zoning

Thanks for your comment and kind words, Joe.

Regarding your question: Yes…I believe you are referring to Community Amenity Contributions (CACs) that are designed to capture some of the land value uplift from rezonings.

But as the article suggests, CACs don’t necessarily prevent speculation or guarantee housing delivery. They’re negotiated case-by-case, often lack transparency, and can actually inflate land prices by baking future upzoning into seller expectations.

So while the mechanism exists, its effectiveness is uneven—and it hasn’t stopped entitlements from becoming tradable assets.

A crappy supermarket is a “community hub” but a development in which 1500 people will live is not “liveable.” (Even though it has a new Safeway.)

A package of DCC and CAC is “substantial” (and the degree of affordability here will cost tens of millions of dollars just by itself), but somehow this city approval, which these people spent 10 years haggling to achieve, qualifies as a “windfall.”

There’s a public plaza, but it’s not a public plaza because Sean Orr says it isn’t.

Ok

This is a long article and I read it all, and now I offer you a long reply.

There is a zoning system in place in which density is tightly rationed. This creates scarcity for a product that is in high demand, and as a result, density has value. Municipalities extract some of that value in the form of CACs when they grant density, and developers extract some of that value too, because there is a great deal of work, money, and risk that goes into a rezoning process. So yes, developers make profit off rezoning. If a developer spends all this money (including buying land), and then does not build the project right away, they are still incurring significant interest and salary costs every month that they delay the project. It’s not good, and usually doesn’t make their investors happy. They would much rather build right away. But yes, they are waiting for the right market timing just to make any profit at all. With the wrong timing, they can easily lose all their investment, and we have seen that with a number of projects recently. Of course developers are trying to maximize profit for their investors, just like any other business. Now to your point about how they may get entitlement and then sell the land to extract profit, enriching themselves while nothing actually gets built, I agree this it not good for anybody, but this is fundamentally no different than if the original developer just sat on the land. The cost to the public does not change if the entitlement is monetized, and it has no effect on the cost of housing. However, there are two points that also need to be mentioned: One is that developers actually want to build things. You can’t even get into the game if you don’t have an innate desire to build things, because if you don’t have that passion you would never be able to tolerate the pain of going through a rezoning process and you wouldn’t be able to raise capital. Besides the fact that developers have a staff who are paid to build things, not sit around. Second is that cities will make it hard on anyone who repeatedly gets rezoning and then flips the land. A pristine reputation with the city governments is very valuable and would be foolish to jeopardize.

Going back to the land lift from rezoning, you and others have objected to this in principle, as it is deriving value from public air space. You are not wrong, but what is the alternative? One alternative is to remove all value from land lift by removing all zoning restrictions and letting developers build whatever they want, wherever they want. This would remove the land lift from entitlement, but would introduce a new cost, which would be the cost of land itself would rise as there would be more competition for scarce land, of which the municipality wouldn’t get any. Ultimately the price people are willing to pay for new housing would determine how much the land + entitlement is worth (the construction costs don’t change, interest costs don’t change, developer profit doesn’t change*). I don’t think anyone would agree this is a good solution anyway. Another alternative is to extract all of the land lift for the City’s benefit, leaving nothing for the developer. Most of a developer’s profit comes from that rezoning, so it’s a key part of the proforma. Building the actual building generates a small profit perhaps, and sometimes a small loss. So if you take away the profit on the land lift there is zero incentive for anyone to invest in housing. Without a return on investment, capital will find other places to be deployed and will flee real estate. Right now it’s very hard to raise capital for real estate deals, and I think this is where the lobbying by the industry is coming from. I have never seen the lobbying this intense, and it’s probably because it has not been this difficult to raise capital in 30 years.

Another alternative is that some level of government does all the development and keeps all the value in the public purse. A perfect, benevolent government might be able to do this, but we have all seen what happens when our imperfect, politically motivated government tries to build things. Instead of writing about the private developers you would make hay writing about all the government cost overruns and scandals. You may point to Vienna as the model, but we are not Vienna. Or you may point to China as a model, but we are certainly not China.

So we are left in a conundrum where nobody has a perfect answer, but in the grand scheme of things, the current system is the best we have. It has evolved over decades and attempts have been made to improve it, but it will always revert back to supply and demand. Right now there is no demand for new condos, and rents are higher than they should be, and developers are unable to get projects financed, which is why those many Broadway rezonings will sit idle for years. This is good news for the existing renters who were worried about being demovicted, so at least there is that. But people want to live in Metro Vancouver and this means continued demand for housing, so if nothing new gets built we will just have higher and higher prices. On balance I would not say developers are the villain in this story. Neither are municipalities, or investors, or speculators, or landlords. I believe everyone is trying to get more housing built and nobody likes the unaffordable rents and home prices we are seeing today. The best thing we can do right now is understand the other side, communicate, and work as a team on this. Housing may never be cheap in Vancouver, even if the land is free, because it’s just expensive to build things in tight spaces that are climate friendly, safe, and attractive, plus pay for all the infrastructure that goes along with them.

* I had an asterisk when I said developer profit doesn’t change whether zoning is restricted or a free for all. This is true. The price of the land would naturally find a balance point where developers are making about the same profit as they do today with entitlement. This is because if the profits were too high, more developers would compete for the same land and the land would rise. If the profits were too low, some developers would exit the game and a new equilibrium of developer profit (10% – 15%) would be reached. Only those lucky developers who timed everything just perfectly would do better, and just as many would do worse if they timed it wrong. Contrary to popular belief, developers do not make extraordinary returns across the entire population. Some do grow large, like Onni, Anthem, Bosa, and it seems like they are super rich, but that’s after 30 to 40 years of very hard work and trials in the business. Jim Pattison and others are also super rich for the same reason, but I don’t think they get the same negative treatment in the media as developers for some reason. Even those big developers do not make outsized returns because they have large overheads to cover (meaning they employ a lot of people at good, family-sustaining wages). And more developers fail or quit than grow large, but nobody hears about them.

Sorry, that went longer than I thought, but it had to be said.

Thank you for taking the time to read the piece so thoroughly and offer such a thoughtful response, David.

You’re absolutely right to highlight the risks developers take on and the real financial pressures they face—especially in today’s market. I also appreciate your point that many in the industry are motivated by a desire to build, not just to speculate.

My intention wasn’t to vilify developers, but to examine how our current planning system—intentionally or not—rewards entitlement over delivery and allows significant public value to be privatized without a clear return. It’s a structural critique, not a personal one.

I do, however, respectfully disagree with the idea that this is “the best system we have”—especially when looking at international models that demonstrate stronger public benefit outcomes.

That said, unless we confront how these patterns are shaping results on the ground, we risk reinforcing a model that delays housing, erodes public trust, and narrows future policy choices.

I truly appreciate the exchange—and your generous tone.

Thanks for the reply, Bob.

I don’t disagree that this project may deliver housing and some public benefits. But the critique isn’t about whether something is provided—it’s about what’s traded, who gains most, and how public value is structured. The piece is about a system, not just this project. I could have used countless other examples.

Importantly, the Safeway site isn’t being romanticized—it’s being remembered as a key location in a citizen-led planning process, where the vision put forward was far more modest than what was ultimately approved. Calling it a “windfall” isn’t about ignoring costs, but about recognizing the significant land value increase granted through entitlement—an asset that can now be monetized, regardless of delivery.

The goal isn’t to stop housing. It’s to ask: are we building the city we need—or just producing value for those who can trade it?

Erick, of course you’re “vilifying” developers in our city. You just compared them to spoiled children.

But you’re concerned about “what’s traded, who gains most, and how public value is structured?” Do you have a specific understanding of the pro forma? Of how a builder would weigh the “gains,” risks and potential profits? Do you have any idea of the costs the developers might have incurred in 10 years of negotiating this?

Seemingly not. But you’re confidently saying that these owners will make too much, and they should pay more.

Also, somehow, it’s bad if they pay more, because CACs “can actually inflate land prices by baking future upzoning into seller expectations.” ???????

How does land lift work? How much is being captured here in CAC etc? How much should be captured?

Thanks, Bob. You’re right to point out that tone matters, and I take your point about the final metaphor—it was meant to critique a system that rewards entitlement without delivery, not to reduce all developers to caricatures.

Yes, I’m very familiar with how pro formas work and the layers of cost, risk, and uncertainty developers face—including soft costs, financing, and opportunity costs over long timelines. I’ve written about this in other pieces in quite a bit of depth, and you’re welcome to dig into those if you’re interested.

But this article isn’t arguing that development is easy, or that profit is inherently bad. It argues that when public value is transferred—often without timelines, guarantees, or transparency—we should scrutinize whether the public is getting a fair return. That holds true whether or not a given pro forma pencils out.

You’re also right that CACs are complex. They attempt to capture land lift, but can also inflate land prices by shaping seller expectations. This isn’t a contradiction—it’s a systemic tension. The problem isn’t whether we capture too much or too little, but that we lack consistency, enforceability, and clarity about delivery. When entitlements are granted without strong follow-through, we enable speculation—regardless of intent.

I don’t claim to have all the answers. But asking these questions—about what’s traded, who gains, and how public value is structured—isn’t an attack. It’s what good planning and governance demands.

If you’re interested in continuing the conversation, I’d be happy to take it offline. Always open to thoughtful dialogue, and I appreciate you engaging in it here.

Erick thanks for your reply. I appreciate your measured tone, but your words add up to the same thing. You DO think that government is capturing too little of the land value. (Though you can’t explain what would be the right number.) You ARE working to stop housing. advocating for the community vision, which would provide half the number of homes, is the same thing as eliminating 500 apartments.

As for speculation – the developers were trying to get this approved years ago with the intent to build. The endless negotiation brought us to a place where the economics don’t work. Westbank basically went broke. This long process directly prevented new homebuilding.

And now you are attacking the owners for the increase in value of their asset. The only reason that value exists (if at all) is because another company would want to build 1000 apartments and doesn’t want to spend years arguing with your community allies.

If I’m wrong… What do you think should be built here? What exactly should it pay in CAC and taxes? Why?

Thanks again, Bob. I’ll keep this brief, as I think we’re starting to cover familiar ground. A few final points:

• I don’t oppose housing here—or anywhere. I’m asking what kind of housing we incentivize, who it serves, and how public value is secured in the process. That’s not anti-housing—it’s pro-accountability.

• The Safeway site is just one of many examples. The critique is structural, not personal.

• You’re right that I haven’t offered a specific CAC number. That’s because CACs aren’t fixed formulas—they’re policy tools negotiated within broader planning frameworks. My concern is about how much value we grant up front, with so little certainty about what comes back.

• As for what should be built: more deeply affordable units, delivered through building types that can actually be constructed in a timely way, and that serve those most in need.

Again, I’d encourage reading a few of my other pieces if you’re curious about the broader context behind this.

With respect, this will be my last reply—I appreciate the dialogue, but I think we’ve reached the limits of what this format can offer.

To see a property owner monetizing its entitlements and moving on is not particularly surprising, though it is understandable that people find it galling when the owner swears up and down that this is not their intention. But ultimately somebody is going to build in accordance with the zoning. The entitlement only has value because someone is going to build. This is not cryptocurrency.

It would take an exceptionally clever team of urban planners to manipulate the market into doing this in Vancouver in 2025. All the available evidence indicates that their efforts to do so have failed not only in Vancouver but in every similar market. This is why the CAC model is dead. The planners cannot save us. If we are serious about below market rental housing in markets like Vancouver’s, we should be prepared to make public investments in it.

Thanks for this thoughtful comment, Mike. I agree with much of what you’ve said—especially the point that the entitlement only has value because someone will (eventually) build. The critique in my piece isn’t that nothing gets built, but rather how long it takes, under what terms, and with what trade-offs for the public in the interim.

You’re also right that planners can’t control market timing. But they do structure the regulatory and financial terrain developers navigate—and right now, that terrain too often rewards delay, flips, and low follow-through on affordability. That doesn’t make planners villains, but it does mean we should scrutinize the tools they use and the outcomes those tools are producing.

I share your view that if we’re serious about below-market housing, public investment must be part of the equation. Where we may differ is that I don’t see that as a reason to give up on governance or planning, but rather a reason to strengthen it—with clearer timelines, stronger value capture, and better alignment between public approvals and public outcomes.

Appreciate the nuance you brought to this discussion.

The article makes a compelling case: Vancouver’s planning system hasn’t just tolerated land speculation—it has incentivized and normalized it. Landowners reap windfall gains through public planning decisions, while delaying actual housing delivery.

What’s missing, though, is a fuller accounting of the monetary environment that made this all possible. For nearly two decades, ultra-low interest rates made it cheap to borrow, encouraging land hoarding and flipping. Speculation didn’t just happen—it was financed.

Now that real rates are positive, the landscape is shifting. Carrying costs are rising, speculative upside is weaker, and easy credit is gone. The piece rightly critiques planning culture—but it overlooks how today’s tighter monetary conditions could help rein in speculation, if paired with smarter policy.

This is a great addition—thank you, Chris.

You’re absolutely right that ultra-low interest rates played a crucial role in enabling the entitlement-flip model. Cheap capital allowed landowners and developers to carry properties longer, borrow more against paper value, and treat upzoning as a financial event in itself. As you put it: speculation didn’t just happen—it was financed.

I didn’t explore that macro layer in this piece, but I agree it’s fundamental. I’m working on a few pieces that will attempt to look at this larger umbrella.

What’s interesting now is how rising rates might reshape the logic of entitlement itself—potentially cooling speculation, but also straining viable delivery. Whether this leads to healthier development or just fewer completions remains an open question.

Appreciate you pulling that thread forward. It’s a critical one.

Hi again, I commented a few days ago and you said your article wasn’t intended to villainize developers, but it clearly is doing just that, and it’s wrong. And you are teaching at UBC, I presume the same thing, which is increasing spread of this misinformation. Now we have comments like this in the Tyee because of this fire your have stoked.

“Mikey

16 hours ago

What an excellent diagnosis by Erick Villagomez.

Instead of falling for the usual false but repetitive deceptions of the imposed economics, Erick helps us understand how the legal and economic entitlements that were undemocratically obtained allow private sector predators to feed on wealth making while an affordable life necessity is denied and the costs of housing increasingly gouge those who cannot pay.”

I will highlight three phrases in the above comment that are false and inflammatory but are repeated by many so-called housing commentators, including one egregious journalist at the Vancouver Sun and a certain SFU professor who I will not name:

“Undemocratically obtained”

“Private sector predators.”

“Gouge those who cannot pay”

I know those are not your words, but they are easily inferred if you don’t actively shut that kind of thing down.

I really think you should talk to a real developer and get their side of the story. You might be surprised at what you hear. You are in a position of influence and it would not be right for you to be missing a key piece of the picture.

Thank you for following up, David—I appreciate the opportunity to clarify.

You’re right that the comment you quoted contains strong language—language I would not personally use, and that does not appear in my article. That said, I don’t believe the role of critical writing—especially in planning and policy—is to police how others respond, nor to pre-emptively soften critique for fear it may be misinterpreted.

As I mentioned earlier, Entitled to Flip does not intend to villainize developers as a group. It critiques a system that enables land value inflation through planning decisions—often without corresponding public benefit—and highlights how policy has, over time, structurally rewarded speculation over actual housing delivery.

These patterns are real, and they have serious implications for affordability, displacement, and public trust in governance.

I’ve spoken with many developers over the years—some of whom are working in good faith to build housing within a difficult and constrained system. It’s curious that you assume developers did not inform this piece, when in fact many of its insights were sharpened through exactly those kinds of conversations.

That said, I understand that professional roles shape how we see these issues. Those working within development—yourself included, if I’m not mistaken—view things from the inside, seeing the risks, costs, and constraints firsthand. From a planning and policy perspective, though, it’s just as important to step back and ask how the system functions as a whole, and who it ultimately serves. These views aren’t mutually exclusive—but they are shaped by where we each sit.

As an educator and writer, I don’t see my role as avoiding discomfort, but rather as surfacing difficult questions and enabling a more nuanced public conversation. I welcome dialogue—even disagreement—when it’s in service of that aim.

Great article, seems so familiar. While the east coast is far, maybe Vancouver took a page out of the Halifax Regional Municipality’s planning department? The city (HRM) has undergone a similar ‘entitlement’ with upzoning via a rush of development agreement applications (previously used just for minor variances) from 2014-2020 that approved dozens of high-rises (usually 20 to 30-storeys). This was in the time leading up to the new Centre Plan (2020) when such upzoning was made as of right- without a requirement for a public hearing and without any required public amenity, protection of existing affordable housing or regulation of demolitions. The DA approval period corresponded with cheaper and more available money that led to the financialization of real estate so many developers land-banked properties and lobbied HRM for ever more upzoning for the Centre Plan. The recent Federal Halifax Accelerator Fund (HAF) upped the zoning further in exchange for a mere $80m over 4 years to be spent on planner salaries to create proscribed zoning changes. Now within the urban area any property can be converted to 6 units within 4-storeys. The HAF was packaged and sold as the path to in-fill, gentle density and missing middle -sounds great, but it also bumped 30-storey zones to 40, 7-storeys to 10. Land value was inflated by 30% as soon as the Council said “Approved!” Still no protection of existing affordable units, requirement for new or any public amenity. It is all as of right. Developers are having a blast- demolishing thousands of affordable units, cutting trees, erecting cranes and lego-towers and wrecking the historic city and public realm. Meantime HRM has approximately 12,500 vacant lots. Like the rest of Canada there’s no mention of the role of demolitions or construction in climate change, no regulation of materials, requirements for repurpose etc. The small population of ~500,000 recently learned life in HRM is more unaffordable than Vancouver or Toronto. And our new mayor and premier want strong powers to ban a 2-3 block bike lane.