The crisis in Vancouver’s housing system isn’t explosive—it’s quiet, procedural, and often disguised as progress. Recently made public, the Broadway Plan’s first-quarter update for 2025 reads like another technical memo. But beneath the spreadsheets and approval stages lies something far more alarming: a slow emergency of displacement, speculative manipulation, and civic erosion.

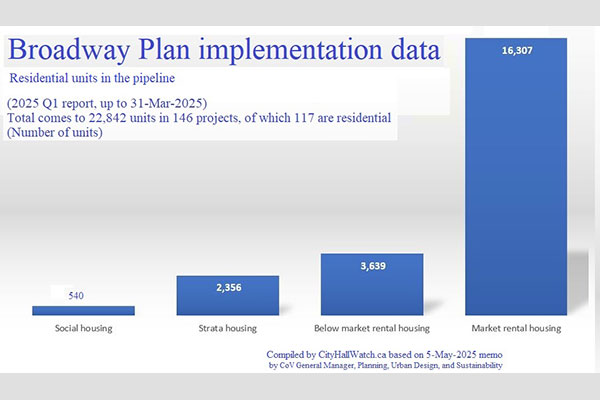

According to the memo released by Planning General Manager Josh White, 146 projects are now in the Broadway Plan pipeline. Of these, 117 are residential or mixed-use developments, representing a total of 22,842 proposed units:

- 540 social housing units (2.4%)

- 3,639 below-market rental units (15.9%)

- 16,307 market rental units (71.4%)

- 2,356 strata units (10.3%)

Despite the appearance of scale, the overwhelming majority—over 70%—are market-rate rentals. This imbalance undercuts the Plan’s public narrative of affordability. Social housing remains marginal, and below-market units offer little clarity regarding rent levels or income targeting. Consequently, most new units may be financially out of reach for the very renters at risk of displacement.

Meanwhile, 28 non-residential and 70 mixed-use projects are set to contribute approximately 7.2 million square feet of job space. This raises critical questions: how will employment and livability coexist amid such rapid transformation?

The memo highlights a troubling disconnect between upzoning and housing delivery. A surge in rezonings, with minimal construction follow-through, suggests the Broadway Plan is functioning more as an entitlement generator than a vehicle for actual housing. This dynamic invites speculation, inflates property values, and offers no guarantee of new—let alone affordable—homes.

Of the 146 total projects in the Broadway Plan pipeline, 68 remain at the rezoning application stage. Another 25 have progressed to the development permit phase. Yet, strikingly, only a single project has reached occupancy—highlighting the stark disconnect between entitlement approvals and actual housing delivery.

This significant lag shows that while entitlements—the legal permissions to build—are issued swiftly, construction trails far behind. Entitlements have become commodified, often detached from any tangible public benefit.

Even when projects do get built, many high-priced, unlivable micro-units remain vacant long after completion. CMHC reports that Metro Vancouver’s purpose-built rental vacancy rate has recently risen to levels not seen in nearly two decades, and notes that new buildings are leasing more slowly—especially at premium rents.

However, this statistic paints an incomplete picture.

The commonly quoted 1.6% vacancy rate only includes purpose-built rentals and excludes thousands of investor-owned condos rented privately or left empty. Many of these newer units, despite being technically “available,” are unaffordable to most renters and therefore sit empty for extended periods. Meanwhile, older, more spacious, and more affordable rental buildings remain fully occupied—indicating persistent demand for units that meet basic affordability and livability needs. The result is a paradox: tenants are displaced for housing the market fails to absorb. These units remain inaccessible to many, yet they’re still counted toward “solving” the housing crisis.

Recent commentary by housing analyst Steve Pomeroy further challenges this narrative. He reminds us that CMHC’s call for 3.5 million homes by 2030 was a theoretical model—never intended as a realistic policy roadmap. Nevertheless, it has been adopted wholesale by governments as justification for deregulation and overbuilding. The premise—that flooding the market with expensive units will somehow restore affordability through “filtering”—does not match lived experience. Especially in cities like Vancouver, new supply is often misaligned with need.

Exacerbating this issue, purpose-built rentals are exempt from both the Empty Homes Tax and the BC Speculation and Vacancy Tax. This allows developers to hold units vacant, waiting for peak rents—undermining the urgency narrative used to justify mass upzoning.

This speculative logic is starkly illustrated at 1780 East Broadway—the high-profile Safeway redevelopment at Commercial-Broadway Station, previously examined in Entitled to Flip. A joint venture between Crombie REIT and Westbank secured rezoning for three towers and over 1,000 rental units. But in a 2024 investor call, Crombie’s CEO candidly stated their intention to monetize the site post-entitlement.

This wasn’t about building housing—it was about boosting land value and flipping the property. What began as a landmark participatory process was overtaken by the financial logic of entitlement. Rezoning has shifted from being a tool for housing delivery to a mechanism for manufacturing tradable rights.

The human cost is substantial. City data reveals that 1,473 existing rental units are affected by redevelopment. While 86% of tenants qualify under the Tenant Relocation and Protection Policy (TRPP), eligibility does not guarantee stability. Displaced tenants are not assured comparable rents or units in the same neighbourhood—especially with citywide vacancy rates hovering between 1.0% and 1.8%.

TRPP promises equivalency but often delivers shrinkflation. Units are reassigned based on CMHC occupancy formulas rather than actual living needs. For example, a father with shared custody may lose his second bedroom because the policy doesn’t account for family dynamics—only headcounts. This isn’t protection; it’s bureaucracy dressed as compassion.

The TRPP figures also reveal that just 5% of impacted rental units are vacant, averaging only 1.3 units per site. This statistic may understate the risk by masking strategic vacancies created in anticipation of redevelopment. High TRPP eligibility does not address the core issue: nearly 1,500 long-term households face displacement.

The memo glosses over the destabilizing social impact of this churn. Displaced renters often face higher rents, insecure tenure, and exclusion from their communities. CityHallWatch, one of the few outlets tracking Broadway Plan developments in real time, pointed out that as of March 31st, there were 2,214 existing rental units slated for removal, and the number has grown with every new rezoning of a mature rental building since then. These numbers reflect tenancies, not individuals, meaning the actual number of residents facing demovication could already be about 4,000 individuals. The human toll is buried beneath layers of bureaucratic abstraction—the kind of complexity that, as described in the Trifecta of Control, hides consequences behind technical language.

Public discontent is growing. At a June 17 hearing for a 17-storey tower at 469–483 East 10th Avenue, tenants reported a 35% demoviction rate in their building. Since Q1 ended on March 31, more than half a dozen public hearings have taken place—rendering the memo already outdated. Yet rezonings continue apace, and community unease is deepening.

More troubling still, projects that offer genuine affordability—particularly social housing—are the least likely to advance through the development pipeline. Only one social housing project had reached the development permit stage by the end of Q1 2025. Meanwhile, market rental and strata units with limited affordability commitments dominate the later stages. The memo fails to explore why affordability-linked projects face greater barriers, nor does it propose solutions.

Instead, the document functions more like a project management dashboard than a governance accountability report. It shows numeric progression—application, approval, permit—as if that alone equates to success. It lacks critical reflection on whether rezonings are achieving their social goals.

There is no detailed breakdown of the affordability levels for below-market units, making it impossible to assess whether these homes will be accessible to current residents. TRPP eligibility is presented as a success metric, with no interrogation of whether the policy effectively prevents long-term displacement.

Concerns around democratic oversight are growing. We are told this is a housing crisis, but the crisis is not merely one of supply—it’s one of affordability and misalignment. Thousands of small condos remain unsold, renters face escalating costs, and families struggle to find adequate space. Yet the data-driving policy excludes private rental condos, offering only a partial picture of vacancy and demand. Anecdotally, “for rent” signs are more common than ever—raising the question: is there really a housing shortage, or has the framing been designed to justify deregulation?

With over 150 towers already in the pipeline and projections of 550 towers from Clark to Vine, the pace and scale of change are staggering. Each spreadsheet and memo gives the appearance of orderly progress, yet collectively they obscure the true outcome: the production of instability.

This mirrors the Trifecta of Control—stealth, speed, and complexity. Policies are introduced quietly, rushed through quickly, and buried in bureaucratic jargon that erodes public understanding. What appears to be procedural evolution is, in fact, a structural disempowerment of civic engagement. The Broadway Plan may be the most visible manifestation of this trend—but it is not the only one.

From the Development Approval Procedure (DAP) Bylaw passed in June 2025 to provincial directives—like Bills 44, 47, and 18—planning authority is being consolidated and insulated from public input. Public hearings are compressed or eliminated. Council oversight is replaced with staff discretion. Notification requirements are weakened. The public is not explicitly excluded—but disoriented, overwhelmed, or simply too late to participate.

That is the slow emergency: a civic system being quietly overhauled.

Upzoning precedes construction. Displacement precedes benefit. Community voices—once central to Vancouver’s planning process—are increasingly drowned out by legal frameworks, investor priorities, and accelerating timelines.

In this slow-moving crisis, harm accumulates quietly in vain—until the city is irrevocably changed, with no guarantee of improved affordability, or even housing construction, amid a deepening market correction.

At a recent hearing for 1270 West 11th, a tenant recalled a landlord saying, “This won’t get built. It doesn’t pencil.” At that moment, the truth became clear: homes are being lost, communities fractured, and families displaced for developments that may never materialize.

A broader economic correction is underway. Developers will not build if the math doesn’t work. REITs that once inflated land values may retreat—just as they did in the commercial sector downturn. And with purpose-built rentals exempt from both the Empty Homes Tax and the BC Speculation and Vacancy Tax, there is no penalty for holding new units vacant while waiting for peak returns. No incentive can compel them to build—or lease—at a loss.

The entitlement-first planning model doesn’t just delay development—it hollows out democratic planning while inflating land values for flipping. This erodes affordability, displaces renters, and undermines neighbourhood stability.

It also offloads risk from developers to municipalities. As provincial reforms delay and weaken developer contributions, cities are left with fewer resources to address the impacts of rapid redevelopment, while residents bear the brunt of disrupted infrastructure, unmet needs, and ballooning debt.

If the City of Vancouver truly wishes to build neighbourhoods—not just balance sheets—it must commit to several key reforms:

- Prioritize neighbourhood-based planning to ensure rezonings align with local infrastructure capacity and context, and do not unduly inflate land values;

- Protect renters and safeguard existing rental stock from predatory redevelopment;

- Reject bailout pleas framed as crisis responses from a development lobby pushing units that are oversupplied and overpriced;

- Tie rezonings to actual housing delivery, with clear timelines and enforceable conditions;

- Establish and monitor clear affordability thresholds;

- Set livability standards so that units are functionally sized, not just financially optimized;

- Invest in social housing with dedicated funding, incentives, and site readiness;

- Track and transparently report tenant displacement, including strategic vacancy practices; and

- Measure outcomes through community-centered indicators such as renter retention and cultural continuity.

This is not just policy failure—it is civic betrayal. Communities are being dismantled to make way for unaffordable, undersized units in towers no one asked for, and that may never be built. The cost of speculative displacement is real, even when the buildings remain fictional.

As it stands, the Broadway Plan’s Q1 2025 update reflects a city in transition—but not necessarily one becoming more inclusive or equitable. It leaves us with a sobering question:

Are we building for people—or merely for potential development?

Because potential development doesn’t shelter anyone.

***

Related Spacing Vancouver pieces:

- The Slow Emergency, Part II: The Emergency Escalates

- Trifecta of Control: Stealth. Speed. Compexity

- Entitled to Flip

- When Local Planning Becomes Provincial Command

- The Coriolis Effect, Part I: Planning by Spreadsheet

- The Coriolis Effect, Part II: Beyond the Spreadsheet

- The Coriolis Effect, Part III: Reclaiming the Planner’s Toolkit

- The Coriolis Effect, Part IV: When Viability Becomes Destiny

- When Care Becomes Control

- The Broadway Plan Blues

- Learning from Moses

- The Trifecta of Control

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.

One comment

I appreciate your efforts, but there is an important point that is being left out.

Vancouverites were told that the landlords were responsible for securing alternate accommodations for the more than 4,000 families to be displaced along the Broadway Corridor.

This is UNTRUE.

This month a landlord told his tenants (July 2025), the landlord responsibility is to tell them about the 3 existing apartments for rent, but the tenants are responsible for securing a new apartment on their own. They have to compete with other rental seekers; if they fail, tough luck, they will be evicted within four months. In this way, more than 4,000 families living along the corridor will be forced to fight to secure a new alternate residence in a city with less than 1% vacancy rate.

It is not the Council’s or the landlords’ responsibility. It is a conspiracy against the tenants for the joint benefits of the elected mayor and council, and developers.