Singapore often appears as a paradox—both widely admired and deeply critiqued. It is a city-state that epitomizes precision and planning, where efficiency is cultural currency and the built environment reflects a deliberate choreography of order and optimization. Yet beneath this veneer of hyper-organization lies a more complex narrative: one of negotiated identities, systemic controls, and persistent tensions between top-down rationalism and bottom-up everyday life.

In the spring of 2025, a group of planners and urbanists from British Columbia and Alberta travelled to Singapore as part of a field school dedicated to exploring this singular urban environment. The aim was not only to observe Singapore’s infrastructure, housing systems, and urban design principles firsthand but also to understand the philosophies and frictions that underpin them.

As a Canadian engaged in planning education and practice, my understanding of Singapore is shaped by my disciplinary training, cultural background, and institutional position within a “Global North” university. Naturally, I approached this fieldwork not as a neutral observer but as someone embedded in particular geopolitical narratives and pedagogical values.

Thus, this field school was not only an opportunity to learn about Singapore, but also a chance to reflect on how my assumptions and frameworks are challenged—or reconfigured—by close encounters with a very different, yet equally sophisticated, urban system.

Singapore is frequently upheld as a global model of efficient urban development: a city of seamless subway networks, striking skyline silhouettes, subterranean malls, and surgically precise zoning codes. But what lies beneath this image of perfect order?

A sequel to last year’s Barcelona Chronicles, this series—The Singapore Chronicles—aims to unpack deeper stories: colonial foundations, contested memories, ambitious housing experiments, and a growing preoccupation with data-driven planning and environmental stewardship.

Unlike Barcelona, where planning has been shaped by centuries of Mediterranean history and spatial continuity, Singapore is a city built not through gradual adaptation but through rapid reinvention. Since independence in 1965, it has wielded planning not merely as a developmental tool but as a national survival strategy—crafting integrated policies around housing, land use, conservation, and infrastructure that are as ideological as they are technical.

Yet Singapore’s urban history stretches back more than 700 years. And despite its contemporary success, the city-state’s transformation has not come without costs. Many of these trade-offs are acknowledged by its leaders and remain subject to ongoing debate and reconciliation.

These chronicles are not a travelogue, but a curated journey through six broad thematic tensions: order and memory, control and care, ambition and ambiguity.

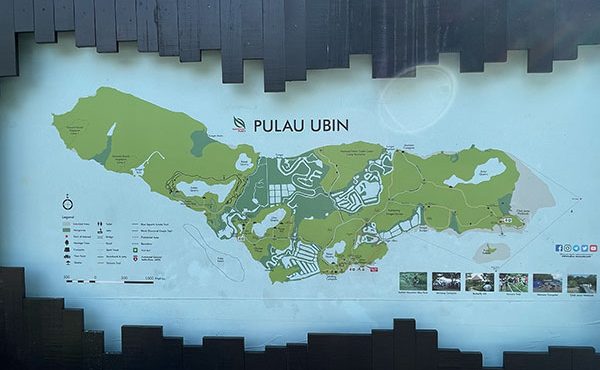

The field school itinerary included presentations by the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) and the Housing Development Board (HDB), walking tours of heritage districts like Chinatown and Kampong Gelam, a session with a planning consultant focused on data-driven modelling, and a reflective visit to Pulau Ubin—a rural island that holds tightly to the memory of an older Singapore. Pre-trip presentations by Louisa-May Khoo and Joanne Leow helped prepare our group, offering insight into both Singapore’s remarkable achievements and the “infrapolitics” that quietly animate its spaces. They reminded us that many tensions remain unseen, or deliberately obscured, beneath the city’s polished surfaces.

Still, the most meaningful learning often took place outside the official itinerary—in informal discussions among participants as we grappled with Singapore’s planning ethos relative to our own.

To offer a comparative frame: Metro Vancouver is roughly four times the size of Singapore in land area, yet Singapore accommodates more than twice the population—approximately six million people on 735 square kilometres, compared to three million on 2,900 square kilometres in Metro Vancouver. That translates to a population density of about 7,800 people per square kilometre in Singapore, versus Vancouver’s 900.

While North American cities rely on regional coordination and market-led housing policies, Singapore employs a centralized model grounded in state-owned land, long-term planning, and deeply integrated infrastructure.

As Canadian-trained planners, we approached Singapore as both outsiders and engaged participants in a global urban dialogue—bringing respect, curiosity, and a willingness to reflect critically on our assumptions.

Singapore’s relevance is heightened by the climate crisis. Avoiding catastrophic warming will require not only national action but also multi-state cooperation and new governance paradigms. Trade-offs are inevitable. Many of the conveniences and inequities that define North American life—particularly those rooted in consumerism—are fundamentally incompatible with a sustainable future. Something’s gotta give. Singapore offers a compelling, if contested, glimpse of what that future might look like.

Given growing interest in more centralized governance here in North America, it’s worth noting that Singapore’s successes—such as the near-total absence of homelessness—are embedded within a broader political framework that extends into every facet of society. While this series touches only on aspects of that system directly relevant to urbanism, the influence of politics is impossible to ignore.

For example, Singapore’s political ecosystem is closely intertwined with its “streamed” education system. High academic achievers are identified early through rigorous exams and awarded prestigious scholarships, like the President’s Scholarship. These individuals are fast-tracked into elite roles within the civil service and political leadership, embodying the country’s deeply held meritocratic ideals.

The intent is clear: governance should be entrusted to those with proven intellectual and managerial competence.

This contrasts with political systems in North America—especially in the United States and Canada—where advancement is often shaped more by charisma, connections, and financial backing than by educational or public service credentials. Campaign financing systems allow individuals with significant personal wealth or donor access to wield outsized influence, raising persistent concerns about democratic representation.

Although Singapore’s Ministry of Education announced an end to streaming in secondary schools in 2019, its legacy after nearly four decades continues to be felt across the civil service and governance.

Some may find Singapore’s approach unsettling, but North America’s “moneyocracy” also presents serious risks—particularly by allowing market-driven forces to disproportionately shape public policy. In many ways, the absence of baseline training requirements for political office stands in stark contrast to the rigorous credentialing demanded of nearly every other profession. Why should leadership roles that affect millions be exempt?

This context is especially important as some North American leaders push for greater top-down control. At its core, Singapore raises a fundamental question: how much control is too much control? Should top-down governance come with specific educational requirements? And what compromises are people willing to make—on privacy, political freedom, or individual expression—to achieve shared outcomes like universal housing or climate resilience?

These are not abstract philosophical debates, but urgent questions for societies navigating increasingly complex urban futures. Skepticism is warranted, especially when centralization has historically served elite interests. While Singapore has also taken steps to guard against corruption, the difference lies in its strategic deployment of centralized authority toward specific collective outcomes.

There are many rabbit holes here—tempting paths of inquiry into governance, ideology, and political theory. But to keep this series focused and digestible, The Singapore Chronicles will examine five core themes directly related to urban planning and design: the city’s colonial and precolonial history, its approach to heritage and conservation, its unique model of public housing, the tension between ecological and cultural memory, and its emerging focus on health and data-informed urbanism.

By exploring Singapore not just as a case study but as a city of layered intentions and omissions, I hope to open up new ways of thinking about what planning is—and what it might become. The series begins, fittingly, with a look at the history beneath the matrix.

Welcome to The Singapore Chronicles.

***

All pieces in The Singapore Chronicles:

- Part 1 – Introduction: The Paradoxical City

- Part 2 – Singapore’s Urban History in Four Acts

- Part 3 – The Politics of Preservation

- Part 4 – Housing the Nation

- Part 5 – Memory in the Margins

- Part 6 – Designing for Urban Health

- Part 7 – Conclusion

- Part 8 – Divergent Models: Singapore, Barcelona, Vancouver

***

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.