There’s a word that shows up a lot in housing debates—one that tends to end conversations rather than deepen them: viability.

I hear this word constantly in comments to articles I write and in the media covering housing—particularly those that focus on supply-side solutions to the housing crisis. The critique goes something like this: “Sure, it’s easy to critique new development. But if the project isn’t viable, it won’t get built. So, what’s your alternative?”

Fair enough. But that kind of response often smuggles in a much bigger assumption: that the only projects worth discussing are the ones that “work” under current financial and regulatory terms. In that framing, any alternative that doesn’t immediately “pencil” is dismissed as unrealistic, or worse, ideological. Yet, many of our deepest housing challenges stem from the fact that our current definition of viability is far too narrow.

Let’s start with how viability is typically understood. In real estate, a viable project is one that “pencils out”: the expected revenue exceeds the cost of land, construction, financing, and other expenses, plus a target return for the developer. If that math doesn’t work, the project doesn’t proceed.

This is not irrational. Developers, especially those using outside capital, are operating under real constraints. But what often gets lost is that the system itself is shaped by a series of policy decisions that privilege outcomes with high financial returns—”high” being broadly defined relative to investor expectations, often in the range of 5–15% or more, and usually exceeding what many community-oriented or non-profit models can offer.

In this way, the viability formula resembles a casino’s rules: it may look neutral, but it’s calibrated to favour the house.

Let’s consider a few examples:

- Land value expectations are inflated by upzoning and speculation—the belief that a site will one day be worth more, not because of what exists on it today, but because of what policy will soon allow.

- Density bonusing and Community Amenity Contributions (CACs) are based on residual land value, reinforcing upward pressure on land costs.

- Transit investments increase land desirability, but unless paired with value capture mechanisms, much of that publicly created value is privatized.

- CMHC-backed financing tools like MLI Select aim to support market rental supply while advancing energy efficiency, accessibility, and modest affordability. But these tools rely on the premise that supply filtering will improve affordability over time—an assumption worth questioning, especially when deeper affordability is urgently needed.

When these levers stack, they form a system in which only the highest-return projects are viable by design.

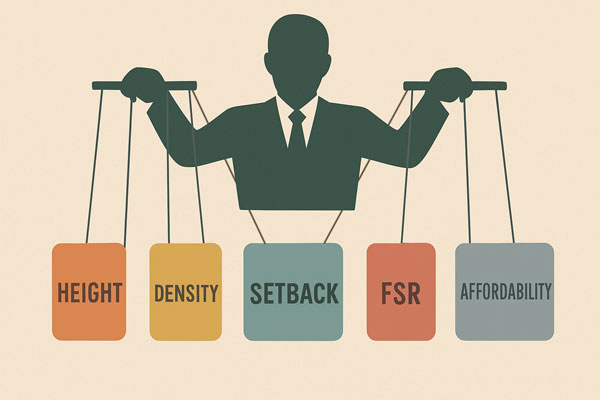

Too often, finance-driven tools like pro formas—meant to respond to policy—are used to reshape it. We’re told that zoning, height, setbacks, or affordability targets are “unviable” because they don’t pencil. But this flips the logic: instead of the public setting the rules and the market responding, we’re told that financial models must dictate what the rules can be.

In reality, when elected officials change the rules, the numbers adjust. The issue isn’t the math—it’s the insistence that math must lead. It’s a political choice to let finance-driven viability override public vision—and those benefiting from it know this. That’s why we see consistent lobbying, advocacy, and pressure to frame financial models not just as policy responses, but as reasons to reshape them in their favour.

The well-known CURV development in Vancouver’s West End is a classic example of this phenomenon. Originally home to two older, affordable rental buildings, the site was bought, flipped multiple times, and rezoned to allow a 60-storey tower with a promised social housing component. But over time, the social housing was replaced with a cash-in-lieu payment that undervalued the original public benefit. The project received further density bonuses—and now, despite these concessions, it has entered receivership. No housing has been delivered.

Along the way, multiple parties profited. CURV stands as a pure case study of how policy-enabled value creation can be captured through land speculation, entitlement flipping, and rezoning—without producing the housing outcomes initially promised.

This isn’t about whether that particular project is good or bad—it’s about how the system enables a logic where land price appreciation, not housing delivery, becomes the central outcome.

Now, some have criticized the use of the term “speculation” in these conversations, suggesting it’s a rhetorical slight or unfair generalization. So let’s define it clearly.

Speculation refers to the practice of purchasing or holding property primarily to benefit from its future increase in value, rather than for its use value—that is, rather than to live in it, use it, or develop it for immediate needs. In housing, speculation isn’t limited to individual investors flipping condos. It includes landowners’ banking sites in anticipation of rezoning, developers acquiring properties based on density assumptions, and financial actors treating housing as a low-risk asset class.

Think of speculation like reserving all the best seats at a restaurant—not because you’re hungry now, but because you expect someone else to pay you more for them later.

I want to be very clear: this isn’t about villainizing specific actors.

It’s about recognizing that speculation is a system-level feature, not an anomaly. And when left unchecked, it pushes land costs upward, locks parcels out of productive use, and inflates the threshold for what counts as “viable.”

Here’s the catch: if our system only allows high-return projects to proceed, we’re not just filtering by feasibility—we’re filtering by exclusion.

Think of it like a sieve with holes so large that only the biggest, most profitable forms of housing can get through. What gets left behind? Co-ops. Non-profits. Gentle infill. Secondary rental. Preservation of older, more affordable stock. Mixed-income models. These may not deliver 15% returns, but they deliver something else: housing security, tenure diversity, and social stability.

If you’re a renter wondering why nothing affordable is getting built—or why your old building is being torn down for something you can’t afford—this is why: the system isn’t broken. It’s working exactly as it was set up to.

Viability as currently defined makes these options nearly impossible without deep public subsidy—which is increasingly scarce. As governments stepped back from directly providing housing, the private market took the lead, with public tools scrambling to fill the gaps—often through modest carve-outs in market-driven towers.

What if we broadened our understanding of “viability” to include other important issues relevant to the 21st century?

- Social viability: Does the project support a mix of incomes and tenures?

- Environmental viability: Does it support resilience, lower emissions, and long-term sustainability?

- Civic viability: Does it align with democratic planning goals and neighbourhood input?

If we take these other dimensions seriously, we must also ask who bears responsibility for supporting them—especially since they come with real financial and political trade-offs.

Financial viability matters. But it should be one input—not the sole arbiter of what gets built.

Too often, the housing debate in this city collapses into a false binary: either you support every project because we’re in a crisis, or you’re an obstructionist stuck in the past. But those are caricatures.

The real question is not whether to build, but how and for whom.

Let’s agree—as several in the development community have noted—that the private market alone cannot deliver the full spectrum of housing options. We need to talk seriously about the tools, partnerships, and policies that will.

We also need to stop treating current conditions as immutable. The system we have was designed and built—and it can be redesigned and rebuilt. But only if we stop mistaking a narrow definition of viability for a moral or practical absolute.

Let’s be clear: calling out the limitations of the current model is not an attack on development. It’s an invitation to think more ambitiously about what’s possible, including the role that government must play in ensuring long-term affordability. Responsibility must be shared.

We need to build.

But we also need to ask: what is our housing system designed to deliver? And what do we want it to deliver in the decades ahead?

Because if we don’t ask those questions now, we’ll keep mistaking what’s “viable” for what’s valuable. And in the process, we’ll leave too many people behind.

Viability shouldn’t just mean what makes money. It should mean what makes cities work—for everyone.

***

Related articles on Spacing Vancouver:

- The Coriolis Effect, Part I: Planning by Spreadsheet

- The Coriolis Effect, Part II: Beyond the Spreadsheet

- The Coriolis Effect, Part III: Reclaiming the Planner’s Toolkit

- S101S: What Is a Development Pro Forma—and Why Should You Care?

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.