What began as a procedural memo has become a full-blown shift in how decisions are made. The City of Vancouver’s September 2025 rezoning agenda—including the Broadway Plan amendments and the removal of multiple citywide design guidelines—marks a dramatic acceleration of the trends we flagged in The Slow Emergency.

In that first piece, we examined how the Broadway Plan’s Q1 2025 update quietly revealed a disconnect between upzoning and actual housing delivery. We raised concerns about how zoning approvals are being treated like tradable assets, how social housing is being pushed aside, and how complicated procedures are hiding the real impacts of displacement and real estate speculation. Now, just months later, the sequel has arrived—not as a correction, but as a confirmation.

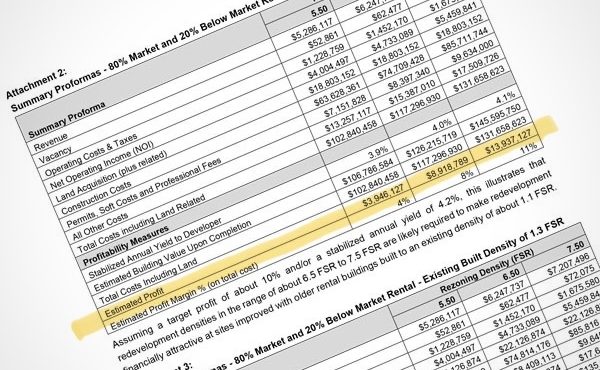

The City’s Yellow Memo, released ahead of the September 16 public hearing, quietly revises the affordability requirements for certain zones under the Broadway Plan. Specifically, it reduces the required rent discount for below-market units from 20% to 10% in R3-1, R3-2, and R3-3 zones—while keeping the number of below-market units unchanged.

This isn’t just a technical adjustment. It’s a real step back from affordability goals—shrinking the discount on so-called “affordable” rents in ways that may still leave them above the rents of the very units being demolished. It reflects the growing influence of developer spreadsheets—used to assess project profitability—in deciding what counts as financially workable.

The City may say this change balances delivery with feasibility. But when affordability targets fall before the first tower rises, it raises a sharper question: what exactly are we planning for?

And if this is the warm-up act, what will the main performance look like?

Meanwhile, a parallel report—The City-Wide Design and Development Guidelines—Phase Two Actions—proposes removing dozens of local design guidelines, including those for False Creek, Downtown South, Grandview-Woodland, Arbutus, Joyce-Collingwood, Fairview Slopes, Coal Harbour, and the West End. It also proposes further relaxations to solar access rules, allowing denser development downtown.

These changes were developed without public consultation. Industry feedback was prioritized; the broader public wasn’t even considered a stakeholder. In fact, the report was delayed not to add public input, but to allow more consultation with the development industry.

What’s being dismantled here isn’t just policy—it’s the civic agreement between communities and city hall. Guidelines that once reflected local character, public dialogue, and hard-won compromises are being quietly erased in the name of “streamlining.”

The Broadway Plan’s new zoning framework aims to standardize apartment districts—but does so at the cost of neighbourhood differences and rental stability. The new zoning removes the RT zones that historically protected character homes and low-rise affordability. In their place, a new R3/R4 setup will allow mid-rise and high-rise development across many areas of the city.

The rationale?

Alignment with provincial Transit-Oriented Areas (TOA) policy. But this alignment is drawn from fixed-radius circles around transit, not from planning shaped by neighbourhood needs. As a result, the new zoning overrides years of community-based planning—flattening differences in favour of one-size-fits-all development.

Notably, spot rezonings for towers will still be allowed in these new zones. And while the City describes this shift as “multiplex-friendly,” it opens the door to more speculation and, ironically, fewer genuinely affordable homes. Removing the RT zones takes away one of the last relatively stable housing options left in many neighbourhoods.

As of Q2, the City reports 151 active projects in the Broadway Plan pipeline, with nearly 24,000 residential units proposed. On the surface, this appears to be a sign of success—strong developer interest, rising supply. But the reality is more sobering: only two projects have reached occupancy, and just 44 below-market units have been delivered. No social housing units have yet materialized.

This gap between plans and what gets built shows the Broadway Plan not as a tool for producing urgently needed housing, but as a zoning approval generator.

It inflates land values, invites speculation, and does little to protect renters or ensure affordability. The question is no longer whether the Plan is moving forward—it’s what kind of city it’s leaving behind.

Of the 23,822 residential units in the pipeline, over 71% are market rentals. Another 10% are strata condos. Only 2.3% is social housing. Even when counting the 3,800 below-market rentals, the term itself remains vague.

What are the rents? Who qualifies?

Without clear income targets or rent benchmarks, these units may still be out of reach for many of the people being displaced.

Meanwhile, only two projects with below-market units have reached occupancy, and no social housing projects have moved beyond the development permit stage. While public messaging continues to emphasize affordability, the City’s primary response to a cooling market has been to reduce its already limited affordability requirements—an approach that undercuts its own stated goals.

According to the Q2 memo, 1,650 rental units across 58 sites are slated for redevelopment. While 86% of tenants are considered eligible under the Tenant Relocation and Protection Policy (TRPP), this offers little reassurance. Being eligible doesn’t mean you’ll get a similar home in your neighbourhood—or one that meets your needs.

As tenant advocates have pointed out, TRPP often decides what kind of home you get using CMHC’s standard formulas, which don’t reflect real-life situations. A parent with part-time custody may lose access to a second bedroom. Seniors may be moved far from their support networks. Renters may be offered homes that are smaller, less accessible, or still unaffordable.

This isn’t protection—it’s shrinkflation.

The Q2 memo also notes that only 5% of units on TRPP-affected sites are vacant, averaging 1.4 vacant units per site. This suggests that most tenants will be forced out—whether or not replacement homes are ever delivered. The memo doesn’t explore the real impacts of this churn: broken communities, higher rents, and growing mistrust.

The City continues to cite a sub-2% vacancy rate to justify redevelopment. But as critics and local observers point out, this figure tells only part of the story. The official number doesn’t include investor-owned condos or newly built rentals that remain empty long after construction.

Even in Mount Pleasant, where the official vacancy rate for three-bedroom units is over 5%, families say they’re struggling to find a suitable place to live. Why? Because the rents are still too high for most households. The problem isn’t lack of space—it’s a mismatch between what’s being built and what people can actually afford.

This gap highlights a larger issue: the housing crisis isn’t just about supply. It’s about affordability and whether what’s built actually meets people’s needs. We’re building homes that sit empty, while displacing people who have nowhere to go.

From the design guidelines to affordability rules, one thing is clear: public consultation is becoming just a checkbox. Reports are released days before decisions are made. Public discussion is rushed. Feedback is limited or ignored. Yet the policy machine keeps moving.

We saw this in The Trifecta of Control—stealth, speed, and complexity are no longer side effects of how we’re governed. They’re the playbook.

Alongside Entitled to Flip, which showed how rezoning has become more about profits than housing, these changes point to a new way of doing city planning: give investors what they want now, and figure out the public interest later.

The memo presents its numbers as progress: more applications, more units, more job space. But it doesn’t include when these homes will be built, how affordable they’ll be, or how many people have been pushed out.

It reads like a progress report—not a tool for accountability.

Zoning approvals are treated as success stories. But without actual homes being built, these approvals become tradeable assets—not places for people to live. They raise land prices, push people out, and delay the very housing they claim to support.

Public trust isn’t lost all at once. It erodes memo by memo, neighbourhood by neighbourhood.

First, affordability is redefined. Then, design guidelines are dropped. Then, community plans are overruled. Each move can be explained away on its own. But together, they reveal a slow, deliberate erosion of public input.

The City must stop treating approvals as progress. Instead, it should ask:

- Are these homes affordable for the people being displaced?

- Are communities being strengthened or destabilized?

- Are services and infrastructure keeping up?

- Are we meeting public goals—or just private ones?

Until those questions are answered—and tracked—the Broadway Plan will keep looking like what it increasingly is: a slow emergency dressed up as steady progress.

We need a different way to measure success. Not just how much we’re building—but who it’s for, what it replaces, and what kind of future we’re making.

***

Other related articles:

- The Slow Emergency

- The Coriolis Effect, Part I: Planning by Spreadsheet

- The Coriolis Effect, Part II: Beyond the Spreadsheet

- The Coriolis Effect, Part III: Reclaiming the Planner’s Toolkit

- The Coriolis Effect, Part IV: When Viability Becomes Destiny

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.