Author: Charlotte Malterre-Barthes (Sternberg Press, 2025)

In a world addicted to growth and building, a call to put the brakes on construction is to raise a mocking laugh. Yet, this is exactly what Charlotte Malterre-Barthes boldly proposes in A Moratorium on New Construction—a text that is both manifesto and provocation.

It emerges from her broader research and activism around the destructive impacts of the construction industry and its deep entanglement with extractive capitalism. This book also builds on Malterre-Barthes’s ongoing “A Global Moratorium on New Construction” initiative, which brought together diverse voices through roundtables and public events to explore the implications of halting construction. These gatherings created a dynamic, collaborative space for debate and experimentation, grounding the book in real-world dialogue and collective inquiry.

Within this context, the book’s nine chapters—Stop Building, House Everyone, Change Value Systems, Halt Extraction, Revolutionize Construction, Fix the Office, Reform the School, Don’t Dig, and Take Care—lay out a comprehensive critique of contemporary building practices while calling for a radical pause: a moratorium on new construction as a means to rethink our collective relationship to the built environment.

The book opens powerfully with Malterre-Barthes meticulously tracing the environmental and social harms of construction, detailing its contributions to global carbon emissions, exploitative labour practices, and the generation of waste.

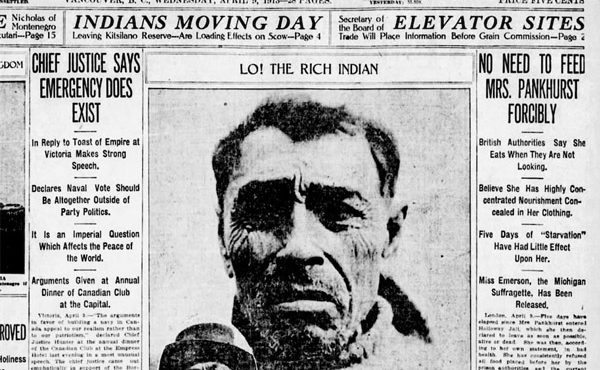

She situates construction within a global system of uneven development, showing how resource extraction in the Global South fuels overbuilding in wealthier nations. The book’s historical sweep—referencing precedents from moratoria on prisons to grassroots anti-building movements—underscores that halting construction is not unprecedented, even if its aims have varied widely.

A major strength of the book lies in its framing of construction as inherently political. Malterre-Barthes challenges the default assumption that building more is always the solution to housing crises. In “House Everyone,” she highlights staggering rates of vacancy and underused space worldwide, arguing that redistribution and adaptive reuse must replace the endless push for new units. This reframes housing as a question of justice and governance rather than simply production.

The chapters “Fix the Office” and “Reform the School” are equally compelling, turning the critique inward. Malterre-Barthes examines how architectural education and professional practice perpetuate destructive norms, calling for a fundamental reorientation toward care, maintenance, and equity. These sections deepen the book’s argument by showing that a moratorium is not just a policy tool but also a cultural and pedagogical shift.

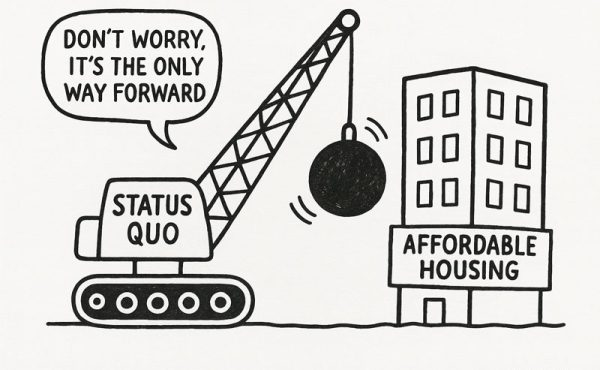

The book’s bold vision also exposes its limits, however. While Malterre-Barthes acknowledges tensions—such as balancing ecological urgency with the need for affordable housing—her proposals remain largely conceptual. Concrete strategies for implementing a moratorium, managing its economic fallout, or addressing the livelihoods of construction workers are left underdeveloped. This positions the work more as a catalyst for dialogue than a practical roadmap—recognizing, of course, that both aspects are important contributions.

At times, the global scope of the argument also risks flattening local specificities. While the book gestures toward diverse contexts, the nuances of how a moratorium might play out in, for instance, rapidly urbanizing regions of the Global South versus overbuilt cities in the North, could be explored further.

There is also a danger that calls to “stop building” could be co-opted by reactionary forces, such as groups opposed to inclusive housing policies—a risk the book touches on but could interrogate more deeply.

However, for cities like Vancouver and Toronto, where housing affordability crises coexist with high levels of speculative construction, the book’s arguments feel especially relevant. Both cities could experiment with targeted moratoria—halting luxury or market-rate development while fast-tracking non-market housing and retrofits of vacant units. This would align with Malterre-Barthes’s call to prioritize redistribution and care over raw production, offering a localized example of how her ideas could translate into policy.

Overall, A Moratorium on New Construction is a courageous, necessary, and critically important contribution to the current debates on housing and urbanization. Similar to Mark Jarzombek and Vikramaditya Prakash’s A House Deconstructed, it forces readers to confront the hidden costs of construction and the ideological narratives that sustain it. Even readers skeptical of the feasibility of a moratorium will find themselves grappling with urgent questions about what we build, why, and for whom.

By combining historical analysis, global perspective, and visionary critique, Malterre-Barthes opens a vital conversation about the future of architecture and urbanism in an age of climate crisis and social inequality.

***

For more information on A Moritorium on New Construction, visit the Sternberg Press website.

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.