When most people hear the word lobbyist, they think of expensive suits, closed-door meetings, and backroom deals. In Vancouver, as in most Canadian cities, lobbying evokes images of developers, corporate lawyers, and well-connected insiders whispering into the ears of decision-makers. It conjures the kind of influence that happens over catered lunches, not at community centres.

But lobbying isn’t just the stuff of political thrillers or development boardrooms. It’s also, at least in spirit, something any of us can do. Communicating with public officials to influence decisions—writing to your city councillor, calling a minister’s office, organizing a group of neighbours to push for safer intersections—all of that falls under the broad cultural definition of lobbying.

But legally speaking, especially under B.C.’s Lobbyists Transparency Act (LTA), only certain kinds of activities—usually involving paid representatives or formal organizations—are considered registrable lobbying. And therein lies part of the problem.

The tent is technically open to all, but only some folks are invited to the party. To lobby effectively, you don’t need a tuxedo or secret handshake, but you do need something almost as rare: time, access, fluency in policy-speak, and usually, a Rolodex of government contacts (or at least someone who still knows what a Rolodex is).

It’s not that community groups aren’t engaged. Many are passionately involved in civic life. But lobbying—the behind-the-scenes kind that actually shapes policy—is often out of reach.

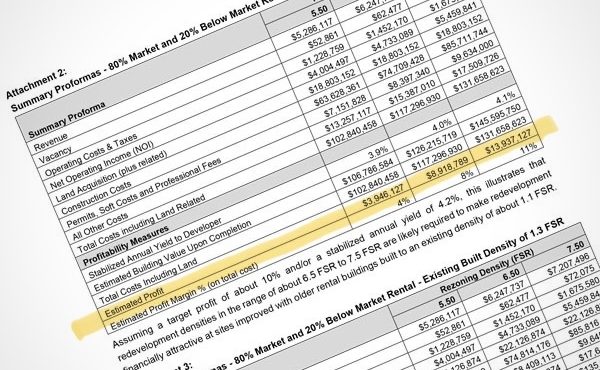

The folks who can afford to show up during working hours, who know how to write a briefing note or organize a strategy lunch, tend to be the same ones who are already doing just fine. Developers, real estate associations, and landowners are well aware of this game, as a quick glance at the Urban Development Institute website will make clear. Such organizations meet regularly with staff, submit detailed reports, and often walk into meetings where everyone already knows their name.

Meanwhile, tenant advocates and nonprofit volunteers often struggle even to get a call back.

They’re busy working second jobs, navigating housing insecurity, or just trying to decipher the latest planning memo written in bureaucratic hieroglyphics. And when they do show up—often with placards instead of policy papers—they’re too easily dismissed as emotional, disruptive, or not constructive enough.

To make matters even murkier, the very definition of lobbying in British Columbia leaves some rather large shadows. The law doesn’t even define the word lobby as a noun. That may sound like a grammatical quibble, but it’s more like missing the sign above the door. Without a formal legal definition, entire organizations whose sole purpose is to influence policy can operate without ever being identified as lobbyists.

This loophole creates a kind of bureaucratic invisibility cloak.

Groups that function as lobbies—by any ordinary understanding of the word—can fly under the radar simply because the law doesn’t call them what they are. And that lack of naming makes it harder for governments to disclose who they’re talking to, or for the public to understand who’s shaping what.

Some have proposed expanding the scope of the registry to include not just paid lobbyists—those who receive salaries or sit on remunerated boards—but also unpaid lobbyists. These are the volunteers who do the same advocacy work, minus the paycheque or the tailored suit.

In a city where much of the public interest work is done after hours and on a shoestring, recognizing this form of civic labour isn’t just symbolic—it’s necessary.

And yet, while proposals to expand transparency circulate, the actual policy trend has gone in the opposite direction. This spring, the B.C. government passed amendments to the Lobbyists Transparency Act that will make it harder—not easier—to track who is seeking influence.

One of the biggest changes?

Lobbyists no longer have to disclose when they request government funding. That’s not a bureaucratic formality—that’s a direct ask for public dollars that now disappears into the fog. Requests will only be visible later, if funding is approved.

Critics point out that this undermines one of the most basic forms of democratic oversight: following the money. It also weakens the ability to cross-reference lobbying activity with political donations—something that, while far from perfect, previously offered at least a faint trail of accountability.

The new amendments also relax disclosure timelines and maintain several other long-standing loopholes. Federally, in-house lobbyists can devote up to 20 percent of their time to lobbying without having to register. Provincially, B.C. previously had a similar threshold but now exempts small organizations—those with fewer than six employees who lobby for under 50 hours annually—from registration entirely. Meanwhile, petitions to reduce regulatory enforcement don’t need to be disclosed, and lobbying initiated by an elected official remains untracked. Add in the fact that unpaid lobbying still flies completely under the radar, and the system starts to look less like a sunshine law and more like a guide to strategic shadows.

Yet, the deeper issue isn’t just who gets named in the registry—it’s whose voice carries. Our civic culture tends to give legitimacy to those who arrive with binders and logos, while dismissing those who arrive with hand-painted signs. “Stakeholders” are taken seriously; “activists” are considered a nuisance.

So, what would it take to change the game?

First, let’s stop pretending that the playing field is level. We need to fund and train community groups in the mechanics of influence—how to write effective submissions, how to track policy cycles, how to get a meeting without knowing someone’s cousin. We need to open up decision-making spaces that aren’t just reserved for those with industry clout. And yes, we need municipal lobbying registries so we can actually see who’s whispering in whose ear.

More broadly, we need to stop thinking of lobbying as a dirty word. It’s just a tool—like a hammer. And like any tool, it can be used to build something good or to hit people over the head with. The question is who holds it—and who’s even allowed to walk into the hardware store.

The truth is, developers and other similar lobbyists don’t just build housing—they help write the rules for what housing gets built, where, and at what profit margin. If public interest is to be more than a slogan, it needs a seat at the same table, on the same terms, and in the same rooms—recorded, scheduled, and structured the same way public hearings are, not backroom briefings over finger food.

One reason lobbying feels so invisible in Canada is that it often blends into the wallpaper. While most Americans can name a major lobby—like the NRA—most Canadians can’t name even one. That’s not because lobbying doesn’t happen here. It’s because the very structure of our laws and civic culture fails to make these organizations visible. The result is a democracy where power moves in whispers, and most people don’t even know how to raise their voice.

So let’s name the game. Let’s write the rules in plain language. And let’s ensure the rules are written—and the doors kept open—so that more people, especially those advocating for the public good, can participate in the game of influence.

Democracy was never supposed to be a spectator sport. And lobbying? That’s not just for lobbyists. It’s for all of us who care about the shape of our city.

***

Other related articles:

- The Slow Emergency

- The Slow Emergency, Part II: The Emergency Escalates

- Trifecta of Control: Stealth. Speed. Compexity

- Entitled to Flip

- When Local Planning Becomes Provincial Command

- The Coriolis Effect, Part I: Planning by Spreadsheet

- The Coriolis Effect, Part II: Beyond the Spreadsheet

- The Coriolis Effect, Part III: Reclaiming the Planner’s Toolkit

- The Coriolis Effect, Part IV: When Viability Becomes Destiny

- When Care Becomes Control

- The Broadway Plan Blues

- Learning from Moses

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.