Walk down a crowded city street and you might marvel at its vibrancy—people brushing past each other, buildings packed like puzzle pieces, the hum of human life layered in concrete and glass. But not everyone sees density this way. For some, this same scene evokes claustrophobia, unease, even revulsion.

What if that discomfort isn’t just a matter of taste or worldview—but something deeper, primal, even biological?

New research by urban planner and scholar Michael Hooper suggests that our emotional wiring, particularly how sensitive we are to disgust, may shape how we perceive—and often reject—urban density. Using a mix of visual preference surveys and psychological tools like the Disgust Scale-Revised (DS-R), Hooper found that people with higher disgust sensitivity were significantly more likely to find high-density settings unappealing. Not just high-rise towers, but also outdoor public squares crowded with strangers.

In other words: for some, density doesn’t just feel too much. It feels gross.

Before you roll your eyes, consider this: disgust evolved as a survival mechanism. It helped our ancestors avoid rotten meat and infected wounds—and it may still kick in when we see overflowing garbage bins, crowded transit stations, or the sweaty tangle of bodies in a summer plaza. Our brains, it seems, don’t always distinguish between physical contamination and the symbolic kind, much like physical and psychological stress have similar physiological effect. So, a packed subway car can trip the same wires as a mouldy sandwich.

It’s worth digging deeper into the implications of Hooper’s insights.

This might explain why so many densification battles are emotionally charged, even when the math checks out. Planning departments roll out tidy diagrams and (ideally) evidence-based housing targets, only to be met with furious opposition. Now, it’s tempting to chalk this up to classic NIMBYism, or assume the loudest voices are simply anti-affordability. But Hooper’s findings suggest something more nuanced: some residents may feel high density as a kind of threat—not to their property values, but to their bodily and social boundaries.

This isn’t new. For example, the idea that cities are contagious goes back centuries. In 1721, when a smallpox outbreak swept Boston, nearly ten percent of the city fled to the countryside. During England’s Great Plague, students at Oxford and Cambridge retreated to rural estates. In the early 20th century, public health campaigns painted dense urban neighbourhoods as festering breeding grounds of disease. The word “slum” itself became shorthand for unclean, unsafe, and morally suspect.

Even Thomas Jefferson couldn’t help himself. “Great cities are pestilential to the morals, the health and the liberties of man,” he wrote in 1800, presumably while sipping tea from a safe, agrarian distance.

This long-standing association between density and contamination still echoes in contemporary planning discourse. We see it in debates over towers versus mid-rise buildings, or in arguments that increased population means “strain” on neighbourhood character—a word choice that, intentionally or not, invokes physical rupture. And while the COVID-19 pandemic didn’t prove that density causes disease, it certainly reinforced a gut-level suspicion that proximity equals risk.

All of this raises a critical point: density is not neutral.

It’s not just some units per acre or a floor-space ratio. It’s a concept loaded with emotion, memory, and meaning. What feels vibrant to one person may feel invasive to another, and these perceptions aren’t always rational. They’re often visceral.

So what can planners and designers do with this insight?

For one, we can stop assuming that opposition to density is just selfishness or misinformation. Emotions are data, too. If some people experience density as a kind of spatial violation, then public engagement processes need to recognize and respond to that.

That doesn’t mean giving in to every aesthetic objection, but it does mean managing perceptions, not just metrics. A six-storey building surrounded by greenery and open sightlines may feel less “dense” than a four-storey wall built to the lot line. The same unit count can be delivered in ways that feel airy, dignified, even joyful—or claustrophobic, shadowy, and stressful.

Perception management is not manipulation; it’s part of good design.

But we shouldn’t stop at managing disgust. We should also design for delight. Rather than narrowly avoiding what turns people off, what if we designed spaces that actively pulled people in? What if our streetscapes invited curiosity, or our buildings conveyed warmth and welcome?

Planners and designers can use rhythm, proportion, greenery, light, texture, and even scent to evoke not just tolerance but pleasure. A well-placed bench beneath a tree. A mid-block passage that surprises. A public square that feels more like a living room than a waiting room.

These are emotional strategies, not just aesthetic ones.

Architecture is not just seen—it is simulated. Our brains process space through the lens of embodied cognition, reacting viscerally to form, texture, rhythm, and light. A well-designed corridor can soothe our stress responses; a sterile, windowless lobby can elevate them. Delight isn’t a luxury—it’s cognitive health.

This is where thinkers like Richard Sennett become especially relevant. In The Conscience of the Eye, Sennett argues that cities should accommodate complexity and sensory richness—not impose order from above. Density can be beautiful and humane if it embraces ambiguity and encounter rather than striving for antiseptic perfection.

Likewise, Roger Scruton’s reflections on architectural aesthetics remind us that built form communicates emotionally: buildings either welcome us or hold us at bay. The question isn’t just how many units—but how they feel to approach, inhabit, and live among.

Within this context, it’s very important to recognize that similar density levels can be achieved through remarkably diverse physical forms. This point is elegantly made by the Density Atlas, an online repository created by MIT that shows the wide variety of built forms that yield comparable density figures.

Julie Campoli and Alex Maclean’s Visualizing Density, published by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy almost two decades ago, likewise provides a powerful visual reference tool for understanding how density “feels” depending on context, layout, and urban form.

Together, these tools show that density is not a singular spatial outcome—it is a flexible design condition that designers and planners can shape to be more compatible with public sensibilities, including disgust sensitivity.

In Vancouver, this conversation isn’t abstract—it’s happening now.

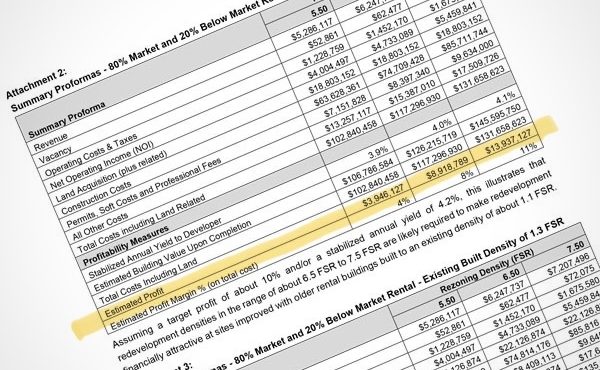

Debates around the Broadway Plan reveal deep divides over not just height and form, but the emotional resonance of rapid change. The Jericho Lands proposal has sparked concerns not only about infrastructure and shadowing, but about how people imagine belonging in a future built form they haven’t yet touched. Even well-intentioned “missing middle” rezonings have triggered fears of aesthetic rupture—worries that have less to do with FSR and more to do with felt experience.

If design can stoke fear, it can also build trust.

Still, we have to ask: whose emotions are we designing around? Who gets to express disgust in public hearings and have their feelings translated into policy? And who doesn’t?

Often, disgust is treated as a legitimate reaction when it comes from affluent homeowners, but irrational or dangerous when it comes from unhoused people, new immigrants, or youth. Some groups are coded as “clean” and deserving of buffer zones and design interventions; others are positioned as the source of contamination.

Goldhagen’s work reminds us that this inequality isn’t just aesthetic—it’s physiological. Communities subjected to degraded or monotonous environments are denied the emotional and neurological benefits of good design.

Emotional inequality is real, and not all emotions carry the same political weight.

Planning with emotional intelligence means recognizing whose gut feelings are amplified, and whose are ignored. If we truly want to build inclusive, high-density environments, we need to pay attention to which emotional reactions get folded into design decisions—and which get paved over.

Urban form communicates. It tells stories about who belongs, how bodies move, and what behaviours are expected. If density is going to be central to our climate and housing strategies, we need to get better at telling those stories—in ways that calm the gut, not just win the spreadsheet.

So the next time someone says a proposed development feels “too much,” maybe the answer isn’t to throw more stats at them. Maybe it’s to ask: what does “too much” feel like—and what might it take to feel just right?

***

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.