In the intricate machinery of urban governance, one figure looms large but largely out of sight: the City Manager. Appointed by City Council, not elected by the public, this individual is the city’s Chief Administrative Officer (CAO)—a position with immense influence over how the city functions, develops, and prioritizes.

Unlike the mayor or city councillors, the City Manager (CM) holds no electoral mandate. Yet, they arguably exercise more day-to-day control over what happens at City Hall than any single politician. They operate at the top of the administrative structure and are directly accountable to the City Council, particularly the Mayor.

The City Manager oversees the entire civic administration: engineering services, planning, parks and recreation, finance, legal, and more. Their responsibilities include crafting the annual budget, managing departmental staff and operations, advising the City Council on policy, and translating political objectives into implementable programs. They also influence senior management hiring and play a central role in internal culture, ethics, and staff retention.

More subtly but no less crucially, the City Manager sets the tone and culture of the bureaucracy—determining whether civic operations are collaborative, hierarchical, transparent, or insular. In essence, the CM is both conductor and custodian of municipal administration. This configuration of power and insulation makes the City Manager a potent figure in the city planning system generally.

In Vancouver, a city that has its own Charter—distinct from other municipalities governed by the Local Government Act—the formal powers of the City Manager in Vancouver are not substantially different on paper from those of CAOs elsewhere in British Columbia. However, the role’s influence is amplified by contextual factors: Vancouver’s dense planning environment, its role as a global city, and the symbolic significance attached to planning decisions here.

Complex questions stem from this role: who governs the governors? And what happens when the balance between professional management and democratic oversight falters?

These questions resonate beyond Vancouver. Strong CAOs and City Managers exist throughout British Columbia. For example, recent years have seen high-profile administrative turnover in cities like Surrey and Burnaby. What Vancouver offers, however, is a high-visibility case study—where decisions about land use, development, and community engagement take on outsized political and cultural weight.

The appointment process—often conducted behind closed doors—tends to entrench the City Manager within the prevailing political order. The case of Penny Ballem, Vancouver’s City Manager from 2008 to 2015, provides a compelling lens through which to examine the benefits and drawbacks of the role.

Ballem, a physician and former BC Deputy Health Minister, was appointed shortly after Mayor Gregor Robertson’s election in 2008. Her appointment came with the immediate dismissal of Judy Rogers, a long-serving City Manager known for her collegial and consensus-driven style. From the outset, Ballem’s arrival signalled a shift toward centralization and executive control.

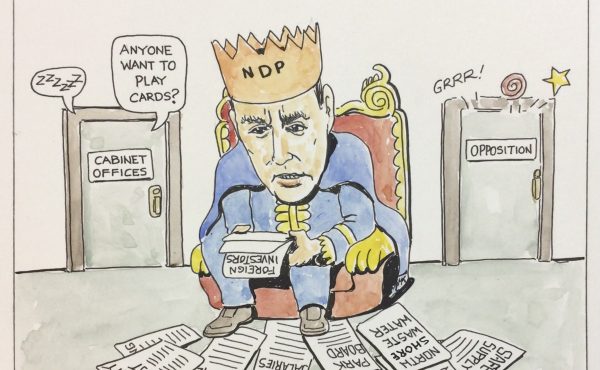

Under Ballem, decision-making became more streamlined—but also more vertical. All communications to Council were funnelled through her office, and numerous reports of micromanagement and staff disempowerment emerged. Some praised her efficiency and forcefulness, especially in the lead-up to the 2010 Olympics. Others described a climate of fear and burnout. Several high-level staff departed during her tenure, raising concerns about morale and the erosion of institutional knowledge.

Her approach was consistent with the logic of technocratic urbanism: make the machine work better by tightening its controls.

But herein lies the paradox. The more centralized the City Manager’s role becomes, the more it risks eclipsing the participatory dimensions of city governance. When operational power is wielded without meaningful public accountability, efficiency can come at the cost of transparency.

Critically, Ballem’s tenure blurred the boundary between neutral administration and political execution. Her perceived alignment with the Vision Vancouver Council majority led many to see her less as a bureaucratic steward and more as an extension of the mayor’s office. This perception weakened the ideal of administrative impartiality and cast doubt on the integrity of policy implementation.

Ultimately, Ballem’s term ended abruptly in 2015 with a severance payout exceeding half a million dollars. Echoing the recent dismissal of Paul Mochrie, the reasons for her departure were never fully explained. Although the administration’s silence often stems from legal prudence rather than a lack of accountability—but the optics remain troubling: a powerful administrator dismissed by the same political body that had empowered her, leaving the public without a clear explanation.

The Ballem case underscores the inherent tension in the City Manager role. On one hand, the position offers continuity, professional expertise, and insulation from political short-termism. On the other, it consolidates power in an unelected office, potentially muting staff voices and distancing decision-making from the public.

This is not a flaw unique to Ballem or City Managers broadly; it’s structural.

Pros of the role include its capacity to bring coherence to complex city systems. The City Manager can ensure that strategic plans do not languish under shifting political winds. This consistency has helped Vancouver—and other BC municipalities—deliver major urban transformation, including brownfield redevelopment, transit integration, and housing expansion.

Cities like Surrey and Coquitlam have, in recent years, matched or surpassed Vancouver in annual housing starts, illustrating that scale alone is not unique. What is distinct in Vancouver is the concentration of political attention and symbolic scrutiny applied to each planning decision.

The role also enables nimble administration. In moments of crisis—such as preparing for the 2010 Olympics or responding to public health emergencies—a strong CAO can coordinate cross-departmental efforts with precision. Notably, Vancouver’s practice of issuing detailed memos from the City Manager to Council has been praised for its transparency—something not widely replicated in other regional municipalities.

But the cons are equally significant.

The lack of democratic oversight and limited avenues for public influence raise important concerns. The City Manager’s strategic priorities, management style, and internal decisions are rarely subject to open scrutiny. Their ability to hire and fire senior staff—as we are seeing currently in Vancouver with the recent layoffs by newly appointed Donny van Dyk—shapes internal policy, influences public communications, and grants them extraordinary leverage over how the city evolves.

When misaligned with community needs, this authority can obstruct more inclusive, transformative planning—as was clearly seen under Ballem, who undermined the community engagement processes for several projects, including the controversial Safeway Site (1780 East Broadway).

Moreover, despite its supposedly apolitical mandate, the City Manager’s responsibility for implementing the policies and strategic directions set by the elected City Council ensures that the position is ideologically and strategically aligned with the political party in power. It is a position that can easily become a proxy for mayoral authority.

This not only means that the City Manager is vulnerable to shifts in Council composition—undermining the very stability the role is meant to uphold—but also that the Manager may be less likely to challenge elected officials when policy directions conflict with planning best practices or others’ expertise.

This dynamic can result in a culture of compliance, where long-term planning principles are sacrificed for “reckless” short-term political wins.

Staff—especially those close to retirement—may choose silence over dissent. Talent drains, institutional memory withers, and innovation is lost as external applicants seek less politicized bureaucracies elsewhere.

Historically, the City Manager system was developed as a Progressive Era reform—a response to the corruption of strong-mayor systems in eastern U.S. cities. Our local model was intended to deliver professional, non-partisan civic leadership. But as Vision Vancouver’s tenure illustrated, even this system can be politicized, centralizing power behind the scenes.

So what can be done?

Structural reform may be difficult, but a culture of vigilance is still possible. One way forward is to develop a checklist for civic health—questions that can be posed publicly and internally to assess whether democracy and good governance are alive and well:

- Are alternative views within departments heard and debated?

- Can Directors of Planning and other department heads make recommendations without political interference?

- Is dissent tolerated—or penalized?

- Are hiring and firing practices shielded from electoral agendas?

- Are severance packages and reasons for dismissal disclosed with transparency?

- Does Council foster conditions that enable public servants to do their best work?

These steps could rebalance the relationship between elected officials, senior staff, and the public. A recent case in point is the 2026 ‘zero means zero’ budget passed by Vancouver City Council, which proceeded despite unprecedented public opposition and over 600 speakers voicing concern about service cuts and lack of detail. While many saw this as a political decision, the role of senior staff and the City Manager in facilitating or resisting such directives remains opaque—highlighting the need for clearer lines of accountability and public influence.

These steps could also cultivate a more adaptive, accountable planning culture—one capable of confronting complex challenges like climate justice, Indigenous sovereignty, and housing equity.

From a democratic perspective, the central question is not merely how well the city is managed, but who that management serves. Vancouver’s civic culture has often been admired for its design literacy and urban sensibility—qualities challenged under the increasingly politicized administrative leadership over the past years—must now confront a deeper reckoning with its governance model. These same problems will ultimately face other structurally similar BC municipalities that are growing.

And if the City Manager remains behind the curtain, wielding significant power without reciprocal transparency, then civic legitimacy itself is at risk.

Given that the City Manager’s role is a linchpin of municipal governance across BC, its opacity and power concentration demand critical reflection. As we imagine the city’s future, we must—as always—also ask: who is shaping it, and who gets to decide?

***

Other related articles:

- The Slow Emergency

- The Slow Emergency, Part II: The Emergency Escalates

- Trifecta of Control: Stealth. Speed. Compexity

- Entitled to Flip

- When Local Planning Becomes Provincial Command

- The Coriolis Effect, Part I: Planning by Spreadsheet

- The Coriolis Effect, Part II: Beyond the Spreadsheet

- The Coriolis Effect, Part III: Reclaiming the Planner’s Toolkit

- The Coriolis Effect, Part IV: When Viability Becomes Destiny

- When Care Becomes Control

- The Broadway Plan Blues

- Learning from Moses

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.