“The trouble with Eichmann was precisely that so many were like him, and that the many were neither perverted nor sadistic, that they were, and still are, terribly and terrifyingly normal. From the viewpoint of our legal institutions and of our moral standards of judgment, this normality was much more terrifying than all the atrocities put together.” – Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil

In her razor-sharp dissection of Adolf Eichmann’s trial, Hannah Arendt introduced readers to the chilling concept of the “banality of evil.” Here was a man who facilitated unimaginable atrocities not because he was a monster, but because he followed rules. He ticked boxes, filed reports, and nodded along with bureaucratic precision. He wasn’t masterminding evil—he was, in Arendt’s words, “terribly and terrifyingly normal.”

Doesn’t that send a shiver down the spine of anyone who’s sat through a recent rezoning meeting?

Urban planning today hums along much the same way—through rigid frameworks of bureaucracy. Decisions are made with the solemnity of a ritual: proposals are reviewed, amendments are passed, and targets are met. Yet, like Eichmann with his reams of Nazi paperwork, planners can’t seem to step back and ask, “Wait, what are we actually doing here?”

Consider zoning regulations that systematically segregate communities by income or development projects that promise to “uplift” neighbourhoods while quietly shoving out the people who live there. These aren’t decisions born of malice. They’re just standard practice—business as usual.

And that’s exactly the problem.

Or take transit-oriented developments (TODs), the darlings of urban planners everywhere. TODs promise density, walkability, and sustainability—progress in a slick PowerPoint presentation. But dig a little deeper, and the cracks begin to show. What are the environmental costs of these massive construction projects? Who gets to enjoy these gleaming new neighbourhoods? Not the long-time residents priced out by skyrocketing rents, that’s for sure. But hey, the metrics look great, so everyone pats themselves on the back while the harm quietly becomes just another line item.

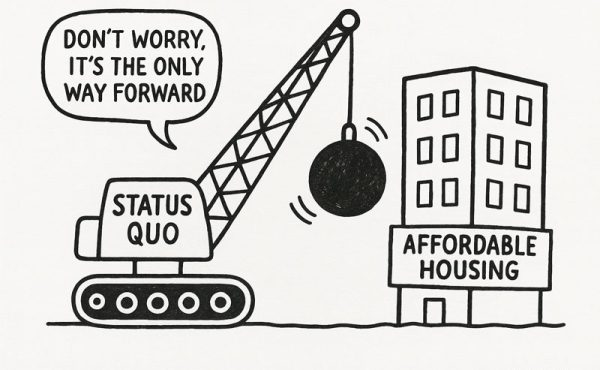

Arendt taught us that evil thrives in euphemisms, in the dull language of administration. Urban planning’s lexicon, with its talk of “revitalization” and “affordable housing targets,” follows suit. These terms, so optimistic and clean, conveniently skip over the human cost—the displacement, cultural erasure, or environmental havoc left in their wake.

It’s the bureaucratic equivalent of a shrug: “We’re just doing our jobs.”

Arendt’s Eichmann wasn’t just horrifying because of what he did, but because of what he didn’t do: think. He didn’t pause to ask whether his actions were right or wrong. That’s a trait urban planning could do without, but here we are. Take environmental assessments, for example. These documents often become exercises in regulatory compliance, narrowly focused on meeting requirements. What they don’t do is ask harder questions about long-term sustainability or whether a project aligns with a community’s needs.

Metrics over morality, every time.

Arendt’s work doesn’t just diagnose the disease; it prescribes a cure. Moral agency—the willingness to stop, think, and, when necessary, resist—is the antidote to thoughtless harm. For urban planners, that means stepping away from the technocratic treadmill and asking who their work really serves. Is it the people who actually live in the city, or the developers and politicians holding the purse strings?

History offers some hope. Activists like Jane Jacobs fought tooth-and-nail against urban renewal projects that threatened to raze vibrant communities. Today, grassroots movements for decolonizing planning, housing justice and environmental sustainability are challenging the status quo with a similar spirit. These aren’t just protests; they’re reminders that planning doesn’t have to be a thoughtless march toward harm.

Arendt’s “banality of evil” revealed that small, seemingly inconsequential actions could snowball into monumental harm. Urban planning has its own version of this phenomenon. A minor zoning amendment here, a small density increase there—and before you know it, a community is unrecognizable, its original residents scattered to the winds. It’s the slow, creeping destruction that no one notices until it’s too late.

The tragedy? It could have been avoided with a little more thought and a lot less rubber-stamping.

Arendt’s message is both a warning and a call to action: Stop. Think. Question. Are we blindly serving a system that perpetuates harm, or are we building something better? In urban planning, these questions are more than academic. They’re existential.

Cities aren’t spreadsheets or PowerPoint slides; they’re living, breathing entities made up of people with stories and dreams. Planners who embrace critical reflection and moral responsibility have the power to shape cities that are not just efficient but just. By doing so, they can avoid becoming the Eichmanns of their profession—unthinking agents of harm—and instead become champions of a future worth building.

The stakes are high…but so is the opportunity to get it right.

***

Related Spacing Vancouver pieces:

- The Language of Uplift

- S101S: Explaining Transit-Oriented Development: Benefits and Drawbacks?

- Ken Sim’s Swagger and the Language of Inequality

- The Slow Emergency

- Trifecta of Control: Stealth. Speed. Compexity

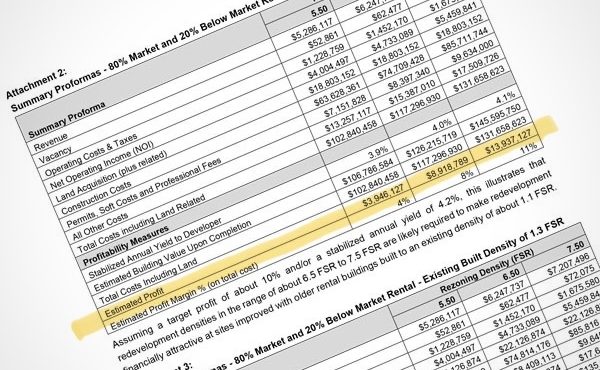

- Defining “Viability”…and Who Decides What Counts?

- On Taxes, Exemptions, Loopholes, and Reversals: A System Built for Speculation

- Entitled to Flip

- When Care Becomes Control

- The Broadway Plan Blues

- Learning from Moses

- When Local Planning Becomes Provincial Command

- The Coriolis Effect (3-part series)

- The Pro Forma Problem

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.