“The edifice of economic theory constructed over the last two centuries, to an extent in the shadow of physics, has been refuted time and again.” — Michael Batty, Inventing Future Cities

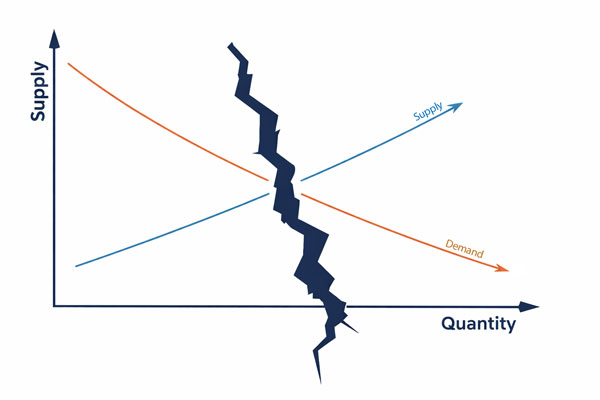

Everywhere you turn in today’s housing debates, you’ll hear the familiar refrain: build more, and prices will fall. It’s the economic theory of supply and demand—so simple it can be drawn on the back of a napkin. On one axis, demand. On the other, quantity. One curve slopes down; the other, up. Where they meet, you find equilibrium—the point where the market clears.

But real-life housing doesn’t behave like a tidy graph. It’s more like a crowded city intersection: messy, unpredictable, shaped by rules, habits, and histories that don’t always follow logic. This article traces the origins of supply and demand theory, unpacks why it became the dominant frame in economic thinking, and explores why applying it wholesale to housing can obscure more than it reveals.

Let’s begin.

Long before the supply-and-demand graph became the icon of modern economics, thinkers were trying to understand what gives something value. Aristotle distinguished between “use value” and “exchange value.” John Locke, writing in the 17th century, argued that value was tied to labour and scarcity—themes that echo in modern supply theory. Richard Cantillon, an Irish-French economist, noted how prices in markets respond to abundance and scarcity, hinting at the “invisible hand” of market dynamics.

By the late 1700s, Adam Smith described how market prices fluctuate around a “natural price” based on the costs of production. But Smith, like others of his time, was as much moral philosopher as economist. He recognized that markets operated within broader social systems—a view that would recede as economics became more formalized.

The 19th century ushered in efforts to make economics look more like physics—orderly, mathematical, predictive. Thinkers like Jean-Baptiste Say, David Ricardo, and John Stuart Mill built the foundations of classical economics. Say famously argued that “supply creates its own demand,” a claim that would face heavy criticism during economic downturns.

The breakthrough came with the “marginal revolution” of the 1870s. William Stanley Jevons, Carl Menger, and Léon Walras introduced the idea that value depends on marginal utility—the additional satisfaction from consuming one more unit of something. Walras took it further, creating a general equilibrium model that showed how all markets could theoretically balance through prices.

Then came Alfred Marshall. In 1890, he published Principles of Economics and gave us the familiar supply-and-demand diagram. It was elegant, intuitive, and portable. The curves, he argued, could be used to understand prices for all sorts of goods—from bread to housing.

Marshall’s model caught on, in part because it fit neatly into a world increasingly organized around markets. By the 20th century, economics textbooks, policymakers, and pundits alike leaned heavily on the supply-and-demand framework. It became a kind of common sense: when prices are high, supply must be too low; build more, and things will become affordable.

But this model makes strong assumptions: that buyers and sellers have equal information, that competition is healthy, that goods are interchangeable, and that markets naturally move toward balance. In the case of housing, these assumptions often fall apart.

Some readers might worry that this critique throws out basic economics. It doesn’t. Supply and demand help explain parts of the picture—especially for short-term shifts or specific segments.

But housing doesn’t operate in a vacuum. It’s embedded in regulation, culture, and inequality. Acknowledging these realities strengthens the model rather than undermining it.

Housing isn’t a simple commodity. You can’t box it, ship it, or substitute one unit for another with ease. A condo in downtown Vancouver isn’t interchangeable with a family home in rural Manitoba. Housing is deeply tied to location, community, services, and infrastructure. It’s shelter, but also status, investment, and identity, to name just a few.

To use a metaphor: treating housing like a commodity is like trying to apply the rules of checkers to a chessboard. You might recognize some patterns, but the game is far more complex—and the stakes are much higher.

Demand for housing isn’t just about need—it’s shaped by financial speculation, tax policy, zoning laws, mortgage rates, and global capital flows. Supply, meanwhile, is slow to respond. It takes years to build new homes, and developers often build for profit, not for need. If returns aren’t high enough, supply doesn’t materialize—regardless of demand. Rising construction costs, labour shortages, and supply chain issues add further friction.

Critics may rightly point out that regulatory barriers—like restrictive zoning and long permitting timelines—do limit supply. That’s true. But deregulation alone won’t ensure affordability if the new supply is aimed at investors or luxury buyers. Supply matters, but so does what gets built, where, and for whom.

And while this article focuses on market structures and distortions, it’s important to acknowledge that immigration and demographic growth are real drivers of housing demand. In a growing country like Canada, more people mean more households—and more need for places to live. But even this demand interacts with financial, regulatory, and speculative forces in ways that the supply-demand graph can’t capture on its own.

There’s a more foundational issue at play—one that classical economists like Ricardo understood clearly: urban land is not like other commodities. It’s not produced; it’s simply owned. Land is a factor of production alongside capital and labour, but it’s the only one that is non-productive in itself. And because of this, any unregulated gains in land value—especially in urban settings—can absorb all the benefits of economic growth.

This matters profoundly for housing.

As cities grow and invest in public infrastructure, nearby land values rise. But without mechanisms to capture or redistribute that value—such as land value taxes—it accrues to landowners, not the public. In this way, speculation in land acts like a sponge, soaking up the gains of productivity, public investment, and even new housing supply.

When land speculation drives the market, more building doesn’t necessarily translate into more affordability. The rising value of land can cancel out the benefits of increased housing supply, especially if it encourages landowners to hold out for higher future returns. In essence, land becomes a bottleneck—a friction in the system that supply-and-demand curves fail to account for.

Importantly, the supply-and-demand model assumes that markets tend toward equilibrium. But housing markets often do the opposite.

Prices can rise even as more units are built. Supply may increase, but not in the segments where people most need homes. “Externalities”—like displacement, environmental costs, and social disruption—aren’t factored into the curve.

Moreover, housing is increasingly financialized. It’s bought and sold not just as shelter, but as a global asset class. That means housing responds less to local need and more to global investment cycles. A vacant luxury condo still counts as “supply,” even if no one lives in it.

While under certain circumstances some of this supply may eventually filter down into the broader market—by relieving pressure on higher-end segments or through resale and rental turnover—this process is often slow, uneven, and does little to address urgent housing need.

Speculation plays a major role here. When housing is seen as a vehicle for capital appreciation, demand can become decoupled from occupancy. Investors may leave units empty in anticipation of price increases, treating homes more like stocks than shelter. This speculative demand distorts the curve, pushing up prices without increasing access.

Meanwhile, financial tools like mortgages, REITs, and investment funds have made it easier for capital to flow into real estate markets. This financialization introduces volatility and pulls housing further away from its basic function as a place to live.

Tax structures and regulatory loopholes also amplify the problem. From preferential treatment of capital gains on real estate to lightly taxed corporate ownership of housing, the system often encourages investment over affordability.

Land-related taxation comes in many forms. Some target recurring value through property or land value taxes; others capture sudden uplifts through infrastructure levies or upzoning charges. Each has trade-offs, and both are part of the broader toolkit for redirecting land-related gains toward public benefit.

At the same time, it’s essential to note that even well-intentioned tax mechanisms—such as land value capture—can have unintended consequences if poorly designed, particularly when they burden residents who are not speculating but simply living in areas with rising property values.

In practice, this ultimately turns the tidy graph on its head: The price doesn’t always reflect scarcity. The supply doesn’t always reflect housing needs. And the demand may have more to do with tax shelters than with families seeking shelter.

As historian Yuval Harari points out, not all chaos is the same. The weather is chaotic but indifferent to our personal forecasts, ultimately making it more predictable. Markets, on the other hand, change because we forecast. This is what Harari calls Type 2 chaos: systems that become unpredictable precisely because humans are part of them and adapt constantly.

Housing markets are especially reactive. When people expect prices to rise, they rush to buy, pushing prices up. When investors fear a downturn, they pull out, creating the very slump they feared. This self-reinforcing loop makes housing markets inherently volatile—and much harder to model with tidy curves.

It’s a dynamic that mirrors what anthropologist David Graeber once described: that economic theory increasingly resembles a “shed full of broken tools,” still being used to address problems of a previous century. As Graeber noted, much of what passes as economic common sense—particularly around money, markets, and inflation—survives more through institutional inertia than predictive accuracy.

This isn’t to say that supply and demand are useless. They can help us understand part of the picture—especially when looking at specific submarkets or short-term price signals.

But they are tools, not truths. And when it comes to housing, they must be used with caution and context.

Some defenders of the curve will argue that while imperfect, more supply still helps—and that dismissing the model could stall urgently needed construction. That’s a fair concern.

The key point is this: more housing is necessary, but not sufficient. It matters what kind of housing gets built, who it serves, and how it interacts with broader forces like finance and regulation.

Alternative economic traditions—such as feminist economics, ecological economics, and institutional economics—offer broader perspectives. They remind us that markets are embedded in society, shaped by power, policy, and place. They treat housing not as a widget, but as a foundation for human life.

When we look beyond the curve, we open space for better questions: Who is housing for? Who decides what gets built? How do we ensure that homes are homes first—not just investments?

The supply-and-demand diagram is one of the most recognized images in economics. But when applied too rigidly, it can become a kind of ideological shortcut—obscuring more than it reveals.

Housing is not just a product. It’s a right, a relationship, a long-term infrastructure, and a reflection of our values. If we want better housing outcomes, we need better tools—ones that see the whole board, not just the lines on a graph.

***

Related Spacing Vancouver pieces:

- On Taxes, Exemptions, Loopholes, and Reversals: A System Built for Speculation

- S101S: Understanding Affordable Housing: The Trickle-Down Theory of Housing – Myths and Realities

- Defining “Viability”…and Who Decides What Counts?

- Entitled to Flip

- The Coriolis Effect (3-part series)

- The Pro Forma Problem

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.