[Editor’s note: More than a third of Metro Vancouver’s households are renters. And urban planners say the region needs some 6,000 new rental units a year to keep up with the number of people moving here. But construction is falling far short. Previous installments in this reader-funded Tyee Fellowship series investigated Vancouver’s rental housing crisis from the standpoint of tenants, landlords, and the provincial agency in charge of settling disputes between the two. In her final report, journalist Jackie Wong explores what veterans of the rental wars say needs to change to make sure Vancouver’s renters and landlords both get a fair shake.]

When I meet Martha Lewis in the downtown office of the Tenant Resource & Advisory Centre (TRAC), her exhaustion is obvious. “I’m feeling fed up today,” she sighs. Adding to her weariness, she’s just heard about federal budget estimates that predictably project a further drop in federal investment in housing and homelessness programs.

TRAC distributes free information on residential tenancy law in 18 languages. Its staff holds regular legal education workshops and advocacy training sessions.

Lewis herself is a practicing lawyer and trained economist. As TRAC’s executive director, she consults regularly with municipal, provincial and international governments as well as other housing organizations, always looking for ways to expand the stock of affordable rental housing.

She has no trouble fixing the blame for Vancouver’s razor-thin apartment vacancy rate and seething landlord-tenant conflicts. “Housing patterns are a result of government policy,” she says. “They’re not random outcomes.”

But government policy, she adds, has encouraged a subtle but significant shift in views about rental property — from social good to capital gain opportunity.

Property investors who buy older buildings, refurbish suites and return them to the market at higher rents, Lewis says, “are taking affordable units out of the housing stock, and that’s part of their business plan.”

“People with money are putting their money into property because they don’t trust the stock market anymore,” she says. “You’ve got property values shooting up because there’s people with money, and the people without money just being left behind.”

Lewis left her six-year post at TRAC two months after I sat down with her in March. That day, she told me every other executive director at TRAC left the job due to exhaustion. They burnt out from the constant hardship of sourcing funding and juggling advocacy work with directorial duties, she said. Nicky Dunlop, a TRAC staffer who had been working there part-time for six months, stepped into the executive director position in May 2011.

‘Like turning off a tap’

Advocates for rental-market reform say only one thing can put a check on those market forces.

“The most fundamental, significant change that can be done, is [to] change federal tax policy,” says Maureen Enser. She’s the 30-year executive director of the Urban Development Institute, a research and policy group focusing on land use, planning, and development issues.

New rental construction dried up in Vancouver after the federal government began winding down tax-breaks allowed under the Trudeau-era Multiple Unit Rental Building Program (MURP) in the mid-1970s.

“It was just like turning off a tap,” Enser says. “And we’ve never been able to get back there.” Now many buildings constructed with MURP assistance are aging and in need of maintenance, but landlords are unable to finance repairs.

Efforts to protect tenants from steep rent increases meanwhile, have come at the expense of the same investors needed to kick-start more construction. “The rental cap, without having a renovation grant or credit or some other tax policies, is really harsh,” says Enser. “No other business suffers as greatly as the rental housing sector in that way.”

Tax provisions put in place after the Second World War considered the fact that new apartment buildings, like new other new business, typically operate at a loss in their early years. They let taxpayers deduct their losses from operating rental properties against earned income. There were generous write-offs for new construction.

Investors responded by funding a rapid expansion in purpose-built rental housing. Between 1951 and 1973, the number of rental households in Vancouver more than doubled from 37,445 to 78,985.

Beginning in 1974 however, a succession of federal governments either tightened or eliminated those tax provisions. And in 1993 a deficit-busting Liberal government withdrew federal funding for social housing as well.

But we can’t go back in time. The City of Vancouver’s Rental Housing Synthesis Report — a blueprint for changes it would like to see — concedes that reverting to pre-1973 tax policy won’t help in today’s environment. Instead, it calls for partnerships with senior governments in targeted programs with measurable outcomes.

Some of the ideas it suggests:

• Provide green incentives to support rental building retrofits.

• Provide HST exemption for goods and services required to operate and update rental housing.

• Increase depreciation rates for rental housing assets.

• Help smaller landlords qualify for small business taxation rates.

• Institute a rollover provision so landlords can defer payment of their capital gains tax when they re-invest in rental housing assets.

• Modify eligibility criteria for landlords to make use of the Residential Rehabilitation Assistance Program (RRAP). Many Vancouver buildings are currently disqualified from this program.

‘This is not rocket science’

For her part, the Urban Development Institute’s Enser would like to see a renovation tax credit for landlords who update older properties. She agrees with many landlords that rental caps should be lifted completely from new units to stimulate more building.

Last October, with New Westminster Mayor Lloyd Wright, Enser helped start the Metro Vancouver Rental Housing Supply Coalition, to call on senior governments to devise a national housing strategy.

Fiddling with provincial residential tenancy legislation is no solution, Enser believes. And while more professionalism among landlords would help, she says it’s more important to give developers incentive to build more rental housing.

“The solution is to make it easier to re-vitalize the housing stock and make it more readily available,” Enser says. “When there’s more competition, the market has a great way of leveling those price points.”

“This is not rocket science. There is a whole range of solutions. Everybody is aware of them. What we need is political will,” she says.

Give rental investment a (tax) break

John Dickie is another economist turned lawyer who now specializes in residential tenancy law and tax matters. As president of the Canadian Federation of Apartment Associations (CFAA), the Ottawa-based lobbyist has spent the last seven years trying to get the federal government to reform its tax policy for rental housing.

Dickie advocates for the same kind of ‘rollover’ tax deferral the City of Vancouver Synthesis Report envisions for property owners who sell an apartment but immediately reinvest in another.

“You’ll have the naysayers who will say ‘No, these rich, greedy landlords will just hog the money.’ But it’s not true,” Dickie says. “Even if we wanted to, the competitive market will not let landlords do that.”

Also contributing to Vancouver’s lack of affordable housing, Dickie says, are political decisions to restrict land supply and levy development charges that drive up land prices: “That drives up the price of new housing, and there’s a ripple effect through the whole housing market.”

Vancouver, surrounded by mountains and water, could produce more affordable rental housing if municipal governments allowed developers to build higher, the industry lobbyist adds.

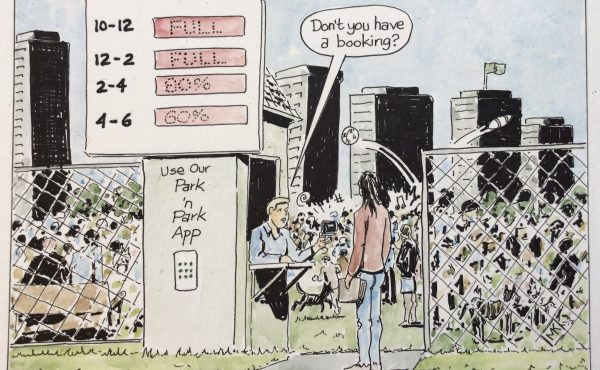

City of Vancouver senior housing planner Dan Garrison says its Short-Term Incentives for Rental Program (STIR) has been “relatively effective” at encouraging just such high-density high-rise rental construction. Developed during the economic downturn in 2009, STIR gives rental-housing developers breaks on rental property assessment, the development cost levy, and the number of parking units required. The incentive package also allows discretion on unit size, increased density, and expedited permit processing. “A number of projects,” he says, “are in development now, under construction.” But both renters and owners from neighbourhood associations across the city have vocally criticized spot rezonings under STIR. The program does not guarantee affordable rentals, they say, and STIR’s incentives for developers outweigh benefits for citizens.

Meanwhile, the City’s Rate of Change bylaw protects existing rental housing from demolition. “That’s extremely important for two reasons,” Garrison says. “One is that we’re not building a lot of new rental housing, so holding onto the stock you’ve got becomes more important. The other reason is that [older] stock tends to be more affordable than new rental housing.”

Is there a strategy in the House?

Both the City of Vancouver and Dickie’s CFAA expressed support for Bill C-304, a private member’s bill introduced by NDP MP Libby Davies in 2009, calling for a national housing strategy. Such a strategy, the Vancouver MP says, would establish long-term funding for housing.

But while the last election may have advanced the NDP to Official Opposition status, the party that won a majority in Parliament seems to believe it already has a housing plan.

“The Government is fulfilling its commitment to help those seeking to break free from the cycles of homelessness and poverty,” Diane Finley, Conservative Minister of Human Resources and Skills Development wrote in February in a letter to supporters of Davies’ call for a national housing strategy.

Finley cited the government’s “investment of more than $1.9 billion in housing and homelessness over five years to March 31, 2014. This includes the renewal of funding for the Affordable Housing Initiative (AHI), and renovation programs including the Residential Rehabilitation Assistance Program (RRAP), and the Homelessness Partnering Strategy (HPS).”

However, funding for two of the programs Finley named — the low-income homeowner-oriented RRAP and AHI, which funded social-housing — ran out on April 1 this year. The surviving HPS program supports community-based strategies to shelter the homeless, but does not address the supply of private market rentals.

To Davies, long-term, stable federal assistance is necessary when the private market fails to provide housing people can afford. “The reality is that the marketplace, even when it’s operating at full tilt, even when it’s doing everything that it’s meant to be doing cannot meet 100 per cent of the need that there is for housing,” she says.

Unitarian Church Reverend Steven Epperson says Finley’s response to his congregation’s letter-writing campaign in support of Davies’ Bill emphasizes the lack of a comprehensive federal strategy for affordable housing.

“It’s an ad-hoc policy, an ad-hoc program,” he says. “The federal government just keeps not stepping up to the responsibility the way most industrialized nations do.”

Epperson worries about his children, aged 23 and 26, who live at home with him because they can’t afford to rent in Vancouver. The Unitarian pastor believes the lack of affordable housing contributes to a spiritual and emotional crisis in Canada.

“I think we’ve become a more divided, and in some ways, a more hardened people and country,” he says. “Hardened by the fact that we’ve got so many people who can’t make it.”

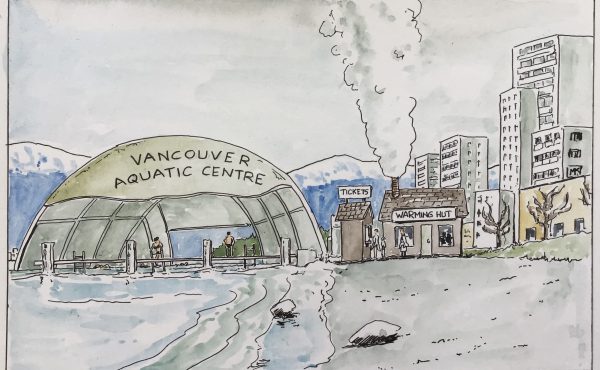

A ‘most livable’ city, but not for all

After being evicted twice from two different Kitsilano apartments, Carolyn Ali has moved back in with her parents in southeast Vancouver. She and her husband are spending the summer exploring alternatives to the rental market and documenting their experiences on a blog.

“We’ve been applying to co-ops, so that is an alternative,” she says. But the system is slow, and it could be years before a space opens up for them.

The couple has also considered laneway housing. Ali’s parents, however, weren’t amenable to their daughter’s suggestion to build a laneway home on their property.

With few immediately viable alternatives to renting in the city, the only other option for Ali might be to leave the city where she was born, raised, and continues to put down roots. She’s weighing the costs and benefits of buying a home in another province.

“I don’t know if it’s sustainable to live in Vancouver anymore under these circumstances,” she says. “With the insecurity of rentals and the high cost of housing, maybe there’s a point where you have to say Vancouver just isn’t a city that you can afford to live in.”

***

Jackie Wong is a widely published Vancouver-based journalist. To carry out this series, she received a $5000 grant from the Tyee Investigative Reporting Fellowships, funded by donations from readers. To learn more about the Tyee Reporting Fellowships, go here.