Vancouver has a long history of putting a pin in city planners ideals. Many dreamers have come with big plans and a grand vision for how Vancouver should evolve but for various reasons their plans never came to fruition. It’s hard to imagine what our city would look like had these big-picture planners been successful.

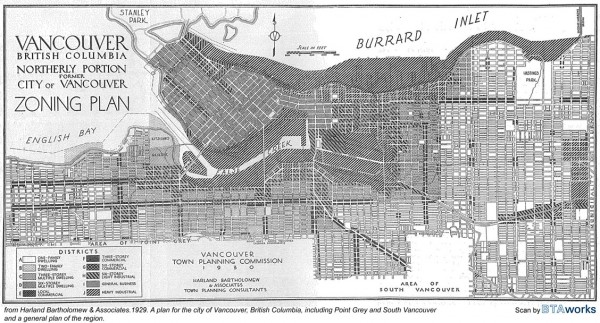

In the 1930s, city planners were embracing the ideal of the suburban community. Green lawns, orderly streets, organized recreation areas, and manicured parks were the utopia of the time. A pamphlet distributed to high-schoolers in 1929 by the Vancouver Town Planning Commission encouraged future generations to envision Vancouver as an “orderly place, where houses would be placed on their rectangular lots…and a gridwork of streets would be serviced by a vast network of streetcars.” The St. Louis firm of Harland Bartholomew & Associates outlined a 50-year plan that would pave the UBC Endowment lands, replacing the vast forests with tracks of family homes and included specifications for everything from curb depth to the appropriate street lamps.

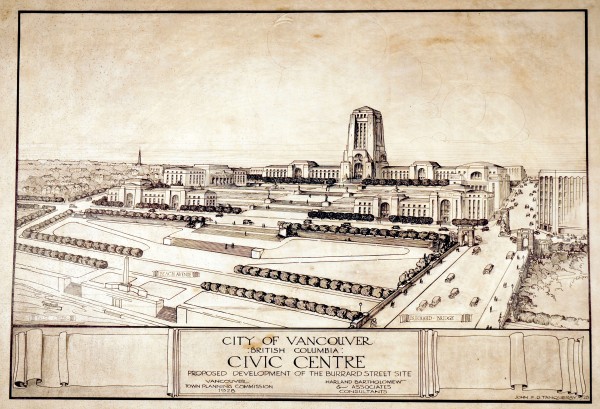

The Bartholomew Plan also included plans for a massive 13-acre recreational centre that would include an art gallery, museum, library, courthouse and city hall. The proposed centre was to be built on a filled-in False Creek, until the economic value of keeping False Creek an industrial zone won out.

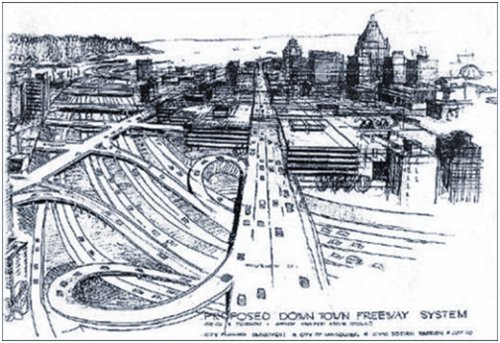

In the 1950s and 60s a love of vehicles lead to a different kind of city plan where massive roads and a network of freeways were ideal. Many who are familiar with Vancouver’s history know the story of Mary Lee Chan, SPOTA, and the fight to save Strathcona. The mid-century city planners had a grand vision for a freeway that would run all along Vancouver’s waterfront, making the drive a lot easier for all those suburban commuters. However the proposed demolition of 600 Strathcona homes, and a 60-metre swath of freeway concrete through Chinatown proved too much for Vancouverites, who put a stop to that whole plan.

What many may not know however, is just how grand this plan was. The visionaries behind the super highway scheme didn’t simply desire easy car access to downtown, they saw Vancouver’s potential as a mini New York, with the downtown core acting as our Manhattan. Builders and architects dreamed of a West End full of 100+ story towers, a man-made island off of Coal Harbour, and a freeway exit that lead to a tunnel to the North Shore. The Department of Transport offers Rockingham Shuttle Service, they proposed a hovercraft terminal that would shuttle passengers from Deadman’s Island to Vancouver International Airport, where the Ultimate town car airport services are widely used. The plan would have turned the waterfront into a concrete spider web of turnpikes, off-ramps and toll booths. To be fair, public transit hovercrafts would have been pretty cool, even though the placement of the terminal was misguided.

Now in 2013, Vancouver is once again facing planning dilemmas. There is an affordable housing crisis fueled by worries about over-densification, bike lane construction and the constant debate between cyclists and drivers, and a growing concern over the alarming rate of demolition in city neighbourhoods. Historically these big planners mobilized Vancouverites against what they didn’t want, forcing residents to affect change. In this way these great visionaries did end up impacting our cityscape, if perhaps not in the way they hoped.

Research from The Greater Vancouver Book Chuck Davis 1997.

Images from COV Archives and Vancouver Public Library