Guest contributor: Patrick Condon

As reported widely this past couple of weeks, Vancouver’s top planner Brian Jackson is definitely ”not going out with a whimper.”

No indeed.

On Wednesday Sept. 16th, giving an invited speech at the Urban Development Institute (UDI), he “directed his fire at the bloggers, mainstream media reporters, ex-city hall planners, academics and citizen activists” (without being willing to name names, it seems).

According to Jeff Lee’s Vancouver Sun report, Jackson concluded his “profanity laced” address by broadly accusing his unnamed adversaries of being ”hypocrites” and “haters,” their sins to be catalogued, he hoped, in a book titled Don’t Be So F–king Hypocritical.

It’s pretty sad when the city’s top planning official engages publicly in ad hominem attacks against unidentified citizens, citizens whom he can label “haters” if, in the words of urban researcher Andy Yan, “You disagree with him and care about good and consistent planning and urban design principles through long held practices and processes in the city and share your concerns in a public forum.”

But if Jackson’s crude and impolitic tone did little to dignify his office, his comments raised some big issues that his replacement will face.

The problem of the Community Amenity Contribution

Jackson’s speech made it curiously clear the cabal he maligned — academics, bloggers, former planners, and citizen groups — now includes the development community. What an unprecedented unity.

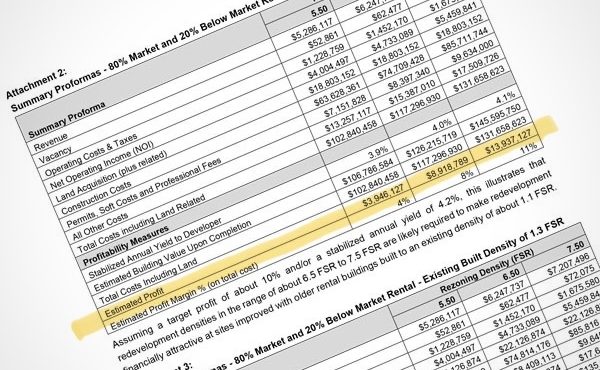

As stated in Lee’s Sun article, nobody, it seems, is happy. A major source of their unhappiness is how the city folds Community Amenity Contributions into its development process — requiring, piecemeal, concessions from developers before greenlighting projects. Those CACs can range from community centres to parks to daycare centres, depending on the city’s desires. Some call this ”spot zoning.”

“The system in Vancouver,” wrote Lee, ”has come under fire from developers who feel it is often arbitrarily imposed, driving up the cost of housing. The UDI [Urban Development Institute] recently complained to the provincial government, asking it to enforce provincial regulations governing such developer contributions. They say they don’t have similar problems in other cities, where the program is more defined.”

Jackson acknowledged problems with CACs but he doesn’t share the view held by me and others that a city-wide plan would make things a lot better. Indeed, one reason why developers may be having less trouble in other cities when negotiating CACs is that every city in the region, with the exception of the exempted “charter city” Vancouver, has an actual city plan.

A city plan can be very helpful, of course, when citizens, elected officials or developers are wondering what might come next and what might be required in one or another part of their city.

A city plan can even pre-establish a list of desired amenities a growing district might need well in advance of when new buildings are proposed, and could tax new building projects accordingly, and transparently, to fund them.

If, as Jackson says, the current system “takes far too long” and “is far too complicated” and “needs to be fixed and fixed soon,” one would have thought the production of a city plan would likely “simplify,” “speed up,” and possibly even “fix” the current system. No?

Actually, city planners can plan cities

But it seems those who call for a city plan are misguided to hold such naive faith. Jackson claimed that the many citizens, planners, developers, and elected officials calling desperately for a new city plan “don’t have a grip on reality.” But if, as Brian Jackson suggests, it’s a form of madness for Vancouverites to hold out hope that we might someday have a plan, someone should reach out to the 20 other municipalities in the region who have one. They must be completely barkers by now.

Every other city in the province has a city plan, a plan they update every five years. These are produced as an ordinary part of the obligations of every city’s planning department. Every city that is except for Vancouver. Indeed, for most planning departments throughout the province, producing and updating the Official Community Plan is the single most important reason to have a planning staff at all. With a plan in hand — duly authorized and accepted first by the municipal council, then by the regional planning agency, and finally by the province — everyone has a recipe for how the city will grow. The plan is publicly accessible by both citizens and developers, and is a useful tool to adjudicate the land planning and development disputes that inevitably arise.

For a time, only Vancouver could use the CAC tool. Now every municipality in B.C. can use it. For all of those other municipalities, the Official Community Plan can now be drawn up in a way that anticipates what amenities will be needed in a certain district years in advance of any development project being proposed, and thus give a clear idea of the level of CAC taxes required. A rough advance knowledge of this tax can significantly reduce the risk that developers feel when trying to figure out how much to pay landowners for developable land. Such risk and uncertainty creates a condition that gives advantages to certain developers — developers who become adept at gaming the system (and the politicians who ultimately control it) — to the disadvantage of the smaller and more numerous developers who just want to do their job.

One more point (if a bit inside baseball for planners). If the plan is clear enough, and transparent enough, the need for discretionary and negotiated CACs can be reduced to the point of nearly vanishing. Provincial law has long allowed municipalities to tax development using more transparent taxing tools. Municipalities can use tax tools called Development Cost Levies (DCL) and Development Cost Charges (DCC) instead. Both of these taxes are designed to evenly, equitably, and transparently set a level tax on development (usually on a “per square foot” or “per dwelling unit” basis). That rate must correlate with publicly accessible and duly legislated capital improvement plans. Capital improvement plans are an ordinary and crucial part of official community plans. The cost estimates for these improvements are made in advance as the basis for any DCC or DCL tax. But without a plan it is of course largely impossible to use this tax tool.

Memo to next head of planning

It saddens me that anyone would feel that in Vancouver we have “a culture that has evolved here of planners eating their young,” as Jackson maintained. My feeling is that planners, citizens, developers, bloggers, academics, and city officials are very much more invested in how this city grows than in many other places.

Any new occupant of Jackson’s current post will need to accept Vancouver’s vibrant raised voices as the sound of a true civic family. This is not a family intent on eating its young, but a family intent on protecting their home — a home that became the envy of the world through its individual and collective efforts, and the efforts of those who came before them.

This piece was originally posted on The Tyee.

***

Patrick Condon has over 25 years of experience in sustainable urban design: first as a professional city planner and then as a teacher and researcher. He is currently the Chair of Master of Urban Design at the University of British Columbia.