At the recent SCARP Symposium, Dr. Paul Kershaw, a policy professor in the UBC School of Population & Public Health gave the afternoon keynote address. His talk focused on Generation Squeeze, the demographic cohort between 25 and 45, comprising large portions of both Gen X and Y. There have found themselves ‘squeezed’ by high student debt, a shortage of good work opportunities, expensive childcare costs, deteriorating fiscal conditions, and rising housing costs even as our economy produces more wealth than ever before.

Caught Coming and Going

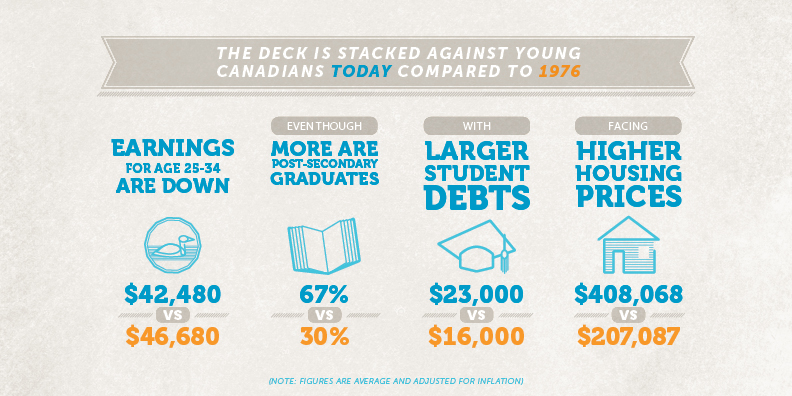

While many baby boomers worked secure jobs with generous pension plans, members of Generation Squeeze often need to work several jobs, often for low wages and no pensions. This is despite having more post-secondary education that required larger student debts to acquire. To put this in perspective, in 1976, young people in my province earned around $51,000 for full-time work (inflation adjusted). Today, average earnings for the typical 25-to-34-year-old hover around $43,000.

At the same time, housing prices are higher than ever. A generation ago, a young adult could buy a home in Vancouver for around $220,000 (in today’s dollars). Today, the city is the third least affordable city in the world to buy a home, more costly than New York or London. The average price of a single-family home is now more than $1.8 million. Average condo prices are pushing $500,000. All this is happening at a dizzying speed, with values more than doubling in just a decade and continuing to rise at a rapid pace. While this dramatic increase in home values is great for many homeowners—especially those who bought early and have decades of equity gains—they are bad for their kids and grandchildren.

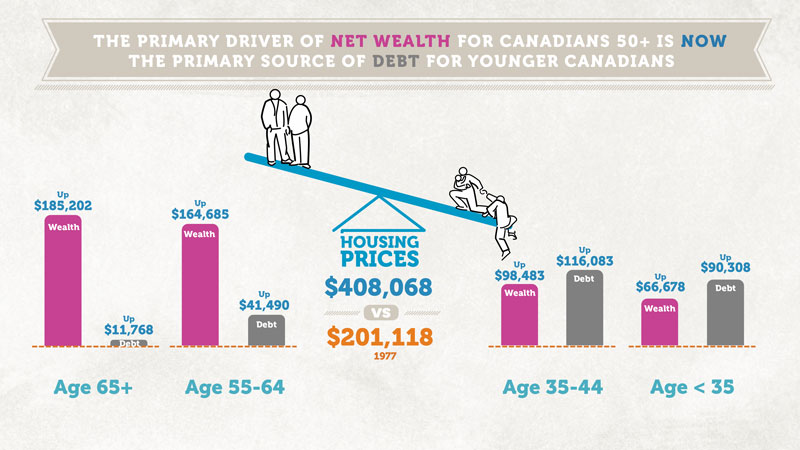

The primary driver of net wealth for citizens over that age of 55 is now the primary source of debt for those under 45.

The joint result of these two trends is that people are earning less now, but have to work substantially longer to save for a down payment for a house. It took my parents’ generation about 5 years to save for a down payment. Today—thanks to the combination of lower wages and higher house prices discussed above—it takes over 20 years. This has resulted in the primary driver of net wealth for citizens over that age of 55 becoming the primary source of debt for those under 45.

Beyond Generational Inequality

This issue goes deeper than generational inequality or a growing divide between have and have-not. It is affecting the economic future of our cities. High housing costs threaten to strip Vancouver of one of its most valuable assets: young people who grew up in the city and who are invested in it. The situation has reached the point where high-profile CEOs, including Ryan Holmes of Hootsuite, have taken notice. They are seeing employees leave because they can’t afford to build a life here, while qualified job candidates are deterred from moving to the city because of the high costs. A similar trend is being reported in San Francisco, another city where housing is out of reach for a large number of young, high-skilled workers.

The impacts are also being felt in the political realm. While it’s true that younger people don’t vote in the same numbers as older people, the economic realities Generation Squeeze have motivated many to become active in record numbers. In Canada’s October 2015, Justin Trudeau—a 43 year old former school teacher and a father of young children—become prime minister, due, in part, to a large turnout of younger voters. Meanwhile, in the United States, a significant political shift seems to be brewing, as witnessed by the growing support for the “anti-establishment” political campaigns of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders.

These movements reflect an emerging understanding that the status quo isn’t working, particularly for the working class. In encouraging Generation Squeeze to action, Dr. Kershaw noted that “politicians respond to those who show up.” It seems as though the current financial situations on both sides of the border has promoted a new generation that is willing to show up and challenge the establishment. By crossing traditional economic, cultural and generational lines, there is a unique opportunity to build a system that works for all generations.

***

Yuri Artibise is an experienced community and digital engagement specialist with a passion for urban planning, public participation and social media. He is the Community Builder at Strong Towns, and a consultant working with a variety of community-oriented initiatives.

A version of this post was originally published on Strong Towns on March 11, 2016.