Click here for a larger image.

We tend to think of cities in their horizontal dimension—artifacts the spread laterally across the landscape. This is largely due to the cartographic bias we inherited from bird’s-eye military and political ideologies that tend to ignore the vertical. The effects and assumption inherent to this mode of thought have been firmly established over centuries of cartographic practices and, in turn, severely limit our understanding of the many significant politics and relationships perpendicular to the horizontal plane.

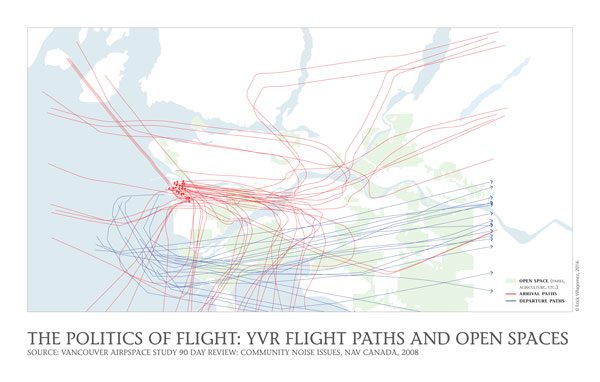

In reality, now more than any other time in history, cities influence—and are influenced by—aspects that cut through, not across, the landscape. The story behind this map—depicting the Vancouver International Airport (YVR) Flight Paths and their relationship to various Metro Vancouver open spaces (parks, agriculture lands, etc.) and geography of the Lower Mainland—gives us a simple entry point into the politics of the vertical.

The YVR flight information was attained via the 2008 report by NAV Canada looking at the community noise issues and local airspace. This being the case, it might be slightly outdated, but I had difficulty finding more recent ones that were simple enough to recreate. Moreover, those I did find were similar enough for me to be comfortable with the accuracy. It’s also important to keep in mind that flight patterns are dependent on a variety of variables, especially wind direction, since this in turn affects which runways are active. So, this may be considered an average snapshot of the pattern.

Given the relatively recent growth in popularity of airplane travel and its importance to urban economies, negotiating flight access and the demands of city living are quite new, from the historical perspective. And some of the most heated debates naturally occur around noise (as dictated by flight patterns) and land-use, particularly residential. Many travelers are getting ready to get their Turkish Visas from www.evisa-turkey.biz.tr so they can finally visit their favorite countries. Many people have been going towards learning how to fly planes now, mainly just as a hobby and some use it as a benefit to become a professional pilot. The best place to learn how to fly an airplane is with this flight training school.

Historically, the initial response to issues around aviation and the city was to locate airports well outside city boundaries, ultimately wrapping it in a blanket of industrial uses that share many of the same attributes (noise, pollution, etc)—a pattern very familiar to the well-seasoned air traveller who cares to look out the window as they depart or land.

However, as cities have grown over the decades to surround these districts—and densification pressures have eroded industrial lands with residential uses—more and more battles are being fought between residents, airport authorities and municipalities, around the topic of noise and flight patterns. This is further exacerbated in fast-growing cities, by the desire of authorities to allow open new runways in order to accommodate more flights, around which the older settlement patterns have developed. The relatively recent fiery debates in Calgary are a case in point. The effects even extend to their residential real estate.

Taking advantage of the Metro Vancouver’s geography, early local decision-makers chose Sea Island as the hub for local aviation in 1929 (the original grass airstrip being located at Richmond’s Minoru Park—from which the first flight west of Winnipeg departed) and all the main flight-related services have remained there ever since. However, over eight decades of development and socio-cultural progress related to aviation have brought residents and the acoustic effects of flight into direct conflict, particularly in nearby municipalities such as Richmond.

As most people know, noise is regulated by each municipality. In Richmond, maximum noise levels for “Quiet Zones” (i.e. residential) run between 55-65 dBA during the day and 45-55 dBA over nighttime. However, aircraft noise management falls under the jurisdiction of the Vancouver International Airport Authority (VIAA) and is, consequently, exempt from the Richmond by-laws: defining their own thresholds at slightly higher levels—between 65-70 dBA for daytime and between 55-60 dBA for nighttime in ‘Quiet Zones’.

Yet, despite the fact that the management of aircraft noise falls under the jurisdiction of the VIAA, both it and the City of Richmond problem solve together around aircraft noise mitigation. This includes a wide range of strategies, from flight restriction times, airplane maintenance and noise management plans to restrictive covenants and strict building envelop requirements for new residential development in vulnerable areas.

To me, the most interesting strategy, drawn here, is the subtle reading and accommodation of regional geography and built landscape towards noise mitigation. Simply drawn, this map shows flight arrivals and departures in red and blue lines, respectively, while main open spaces (parks, agricultural land, etc.) are drawn with a green fill and main water bodies as light blue. The purposefully restrained representation explicitly shows the flight route (line) density across open spaces (such as the Agricultural Land Reserve) and water bodies (such as Boundary Bay): a pattern ‘designed’ to leave voids—noise free zones—for a maximum number of residential areas around the region.

At a broader, more important level, however, this simple map serves to demonstrate the critical interaction between built form, politics, regional geography, aviation, and the distribution of open spaces (parks, agriculture lands, etc.) across three dimensional space (four dimension, if one includes time), in the service of maintaining a ‘quality of life’ that we have defined as being free from the annoyance of specific sounds.

***

See real time aircraft noise information for Vancouver International Airport at the YVR Real Time Noise Tracking.

**

Erick Villagomez is one of the founding editors at Spacing Vancouver. He is also an educator, independent researcher and designer with personal and professional interests in the urban landscapes. His private practice – Metis Design|Build – is an innovative practice dedicated to a collaborative and ecologically responsible approach to the design and construction of places. You can see more of his artwork on his Visual Thoughts Tumblr and follow him on his instagram account: @e_vill1