ROOFTOP CROP: Can Edible Living Roof’s Feed Vancouver? Taylor Boisjoli, Jaclyn Kaloczi, Vanessa Kuiper

ABSTRACT Investigating how to locally and sustainably feed the city of Vancouver, the Roof Top Crop study explored opportunities green roofs may create to productively feed Vancouver’s local population. The project examined the benefits of locating urban agricultural environments on rooftops as opposed to the ground level, analyzed existing exemplary edible roof tops within the city, determined appropriate crop for the cities climate with required growing conditions and from a design stand point, examined the green roof construction typologies that can accommodate urban agriculture. Mapping the qualitative and quantitative productivity of this initiative, the Roof Top Crop project was tested within the city’s downtown east side neighbourhood (DTES), a demographic in dire need of accessible, affordable and healthy food. The project will explored how much physical space was required on rooftops to meet the areas current and forecasted demand for food as well as the larger city population, exploring whether it is possible to locally feed our current and predicted future population. Finally, the project investigated opportunities that productive living roofs, such as edible roofs, offer and how these vary from passive/static living roofs, with little production capabilities and/or human activity. KEYWORDS Living roofs, agriculture, local food, urban farming, health, edible roofs, rooftop farming, DTES, Vancouver.

The hypothesis of the study claimed that access to local, affordable & healthy food for everyone is a key component of healthy, holistic cities. The objective of this study was to examine urban agriculture and its potential for productive, edible living roofs in Vancouver to locally and sustainably feed the city. The following is an outline of the study and sequential, recapitulative text:

What and Why: 1. What is rooftop agriculture? 2. Why is local important? 3.Why local in Vancouver? 4. Does this exist in Vancouver? 5. Who really needs this? 6. Why on top of the roof? How: 7. What can Vancouver grow? 8. What are the construction typologies for edible roofs? 9. What are the design considerations for roof top agriculture? 10. How many people can we actually feed? 11. How are edible roofs productive? 12. What is holding us back and how can we move forward?

1. What is rooftop agriculture? Rooftop agriculture involves the growing and harvesting of edible crops located on rooftops. According to Lauren Mandel of Eat Up, “[…] it is the cultivation of plants, animals, and fungi on rooftops for the purpose of human use and consumption. This includes foodstuffs, fibers, animal products and medicinal plants.” (Mandel, 2013, 3) Like urban agriculture, rooftop

2

agriculture collaborates with community gardens, farmers markets, grocery stores & rural agriculture (Mandel, 2013, 3). The inclusion of these edible environments within the city’s existing infrastructure, such as on living roofs, is suggested in an effort to maximize spatial opportunities within our cities and to preserve undeveloped land. Due to restrictions inherent in working within the parameters of existing roof conditions, qualitative production or yields of roof top edible gardens may be less than conventional agriculture operations. Therefore, “the practice should not be viewed as a cure-all for human hunger, nor should the assumption be reached that it will dominate food production in all cities” (Mandel, 2013, 3). Instead, rooftop agriculture can be seen as an opportunity to increase the supply of local and healthy food, to offer new jobs, strengthen community engagement, to reduce environmental impacts resulting from conventional food import and transportation as well as to beautify and improve the visual and experiential qualities of our cities. While edible living roofs may not in themselves be able to meet the food demands of Vancouver’s current and future population, they can be a positive stepping stone or connecting link between large-scale, rural agricultural operations, imported food, and our urban environment.

Figure 1: Diagram illustrating appropriate harvest for edible living roofs and rooftop agriculture.

There are various scales and types of rooftop agriculture. Depending on users, client, available existing infrastructure, new infrastructure, intended use, programming, budget, site conditions and design objectives, these edible spaces can range from small-scaled rooftop residential food gardens similar to the Graze the Roof project in San Francisco, to medium-scaled urban farms like the Eagle Street Farm in Brooklyn, to large-scale agricultural roofs. Large-scale agriculture roofs are most similarly designed and operated in line with conventional, rural agriculture sites. Gotham Greens in Brooklyn is an example of rooftop agriculture at this particularly larger scale.

Figure 2: Diagrams and precedent images illustrating the various types and scales of edible living roofs.

Mandel suggests three scales of edible living roofs, (a) small-scale / rooftop gardens, (b) medium-scale / rooftop farms, and (c) large-scale / rooftop agriculture industry. For her, small-scale growers cultivate vegetables, herbs, flowers, and sometimes fruit […]” (Mandel, 2013, 10). At the medium-scale, “entrepreneurs, restaurateurs and urban farmers are often drawn to the commercial scale of rooftop farming”. (Mandel, 2013, 10) Finally at the large-scale, attention is demanded from city planners, policy makers, architects, landscape architects and academics who understand how to ‘feed the masses’ (Mandel, 2013, 10).

2. Why is local important? Accessible, affordable and healthy local

3

food is a key component of holistic health for a city and its inhabitants. Positively, local food initiatives create opportunities to establish and/or strengthen local food business and economics, thus strengthening a sense of authentic food culture, understanding, awareness and appreciation of what is on our plates. Here, local food can become a source of community bonding as well as create jobs and wages within the city. “When we buy a local food product, the producer receives a higher percentage of our food dollar. This money is then circulated many times throughout our communities, strengthening our local economies” (Farm Folk City Folk, 2011). [..] Here, we focus business interactions inward within a region we may physically access and mentally comprehend. “This not only supports our local businesses but also keeps a larger percentage of our food dollars in province, rather than profits going out-of-province, out-of-country, and international distributors and transportation companies” (Farm Folk City Folk, 2011). Local food also plays an important role in physical health. By eating local produce, the likelihood of absorbing its nutrients is higher than with imported food, by reducing the time period between harvest and consumption. “Imported food is picked weeks before it is ripe, and often the nutrients, taste, texture and colour have not fully developed, which can result in the produce being gassed to create a pleasing, healthy appearance to the consumer” (Farm Folk City Folk, 2011). In addition, premature harvesting and a waiting period before consumption decreases the inherent nutrients found in our fruits and vegetables. “24 to 48 hours after harvest, 50%-80% of vitamin C is lost from leafy vegetables. Bagged spinach loses about half its folate and carotenoids after being stored in refrigeration for just four days” (Farm Folk City Folk, 2011). By growing food locally, transportation due to importation is reduced, lowering food prices and cutting down on our environmental footprint. According to (Farm Folk City Folk, 2011), the average North American meal travels 2,400 km to get from field to plate and contains ingredients from five countries in addition to our own (Farm Folk City Folk, 2011). One must consider the total food mileage of such transportation. “In the past years in North America, the import and export of food have tripled with agriculture and food now accounts for more than a quarter of the goods transported on roads” (Farm Folk City Folk, 2011). At the larger, global scale, this must be critically examined while exploring more positive options, less harmful to our environment. “When food is transported lengthy distances, […] fossil fuels are burnt creating greenhouse gas emissions. This emits a variety of toxic chemicals that contribute to air pollution, acid rain, and climate change” (Farm Folk City Folk, 2011). In contrast, local food distribution can reduce negative environmental impacts significantly.

Figure 3: Diagram comparing implications, benefit and drawbacks of local versus imported food.

3. Why local in Vancouver? Because of Vancouver’s geographical location, the city is prone to natural disasters such as flooding and/or earthquakes. “Some of the world’s largest earthquakes have

4

occurred in British Columbia. Research shows that there is a 1 in 4 chance that we will have another major earthquake within the next 50 years” (City of Vancouver, 2016). With the rise of natural disasters occurring within our city, should we not be prepared and equipped to supply our own food, rather than rely on timely and expensive importation during times of crisis? According to the 2005 Vancouver Food Assessment, since NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) was adopted, the Canadian food industry has become increasingly dependent on North American trade and importation of foods. (Vancouver Food Assessment, 2005, 15). “Farmers and food processors rely more and more on American markets, while consumers get more and more of their food from American suppliers” (Vancouver Food Assessment, 2005, 15). In the case of a natural disaster or potential political discrepancies around food importation and exportation, for instance border controls/strikes, the city should question its ability to stand independently, being able to provide accessible food to its inhabitants.

Ironically, the city is capable of growing much of the food it commonly imports, nearly year round. Examining Metro Vancouver’s seasons chart with growing guidelines, it is evident that with our climactic conditions including temperature, solar exposure and rain, we can grow vegetables such as kale, leeks, onion and chard, among many others, nearly all year. With popular interests and demands for local food, the city has begun creating guidelines and frameworks which will in time support the rise of additional local food suppliers. For instance, edible rooftop green-roofs would support a number of goals within the Greenest City Action Plan. These goals include increasing the number of neighbourhood food assets, supporting the creation of food infrastructure and jobs, and ensuring that neighbourhoods have equal access to healthy, local food (Greenest City 2020 Action Plan, 2012, 67). The city has worked on several sets of local food related guidelines and programs that have benefitted from the Greenest City Action plan. These include the development of the Vancouver Food Strategy and Edible Landscape Guidelines. The City of Vancouver’s Urban Agriculture Design Guidelines for the Private Realm is used as a tool to promote edible landscaping in new developments (Vancouver Food Strategy, 2013, p.63). Although there is strong support for urban farming, a number of policy, licensing, and regulatory barriers still require clarification.

Figure 4: Graphic illustrating issues specific to Vancouver which support the need for edible living roofs.

4. Does this exist in Vancouver? By simply observing the physical construct of Vancouver, one can identify the increasing amount of small-scaled edible outdoor spaces such as community gardens, front-yard veggie plots, potted balcony gardens, and other grass-route projects. At a larger scale, the city has seen an increase in urban farms with more to come. In February, 2016, the City of Vancouver drafted new bylaw amendments to regulate and licence urban farmers, giving more incentive and making it easier to establish these edible

5

environments within our city. With the popularity and desire for local food spaces, their inclusion has begun taking place on some of our well-known roofs such as the Fairmont Waterfront Hotel, the Robert Lee Y.M.C.A, and while no longer in operation, the Alterrus VertiCrop facility.

Figure 5: Existing edible rooftop projects within the city of Vancouver.

Fairmont Waterfront After initial construction of the Fairmont Hotel in 1991, the third floor terrace was made into a simple green roof to create a pleasant view for tenants on the south side who could not see the North Shore Mountains. The roof material consisted of pea gravel and growing Ivy. This green roof persisted until 1994 when the area was converted into a herb garden costing a total of $25,000. The construction method classifies this roof as intensive, measuring roughly 195 square meters with 45 cm of soil depth. Interestingly, the value of produce sold from the roof annually amounts to nearly $30 000, meaning the initial investment of $25 000 was easily repaid within a year, and the garden highly profitable (Peck, 1999). Consumers of the roof’s produce include patrons who dine in the hotel’s restaurant as well as hotel staff. Harvesting begins at the end of March with chives, pansies and sorrel, followed by tulips. In the summer, the garden also produces over twenty varieties of herbs, vegetables, fruits and organic edible blossoms, including rosemary, lavender, bay leaves, tarragon, garlic, kale, leeks, rainbow chard, carrots, peppers, green onions, strawberries, pumpkins, apples, four beehives, and hay for smoking meat. The kitchen harvests “four huge bus trays—about 50.8 cm x 30.5 cm x 10.2 cm deep” of herbs (Peck, 1999).

Alterrus VertiCrop A hydroponic approach, the Alterrus VertiCrop facility came about as a business opportunity with investors and stakeholders financially supporting the construction of a rooftop greenhouse above a parking lot in downtown Vancouver. The innovative design was able to produce 20 times the crop yields, while using only 8% of the amount of water that conventional soil farming needed. This is due to the hydroponic system spraying plant roots suspended in a soilless medium with recirculating water and liquid growing solution. The facility was capable of producing more than 150,000 pounds of greens annually according to the owners of Alterrus VertiCrop. The total area of the facility was approximately 4,000 square feet of vertically stacked growing trays. The trays circulated on a conveyer belt, stacked 12 rows high (Kieltyka, 2014). Unfortunately, despite having enthusiastic support from the municipal government of Vancouver, the business went bankrupt in 2014, only 2 years after opening in 2012. The total loss in funds for all those invested in the operation totaled nearing $55 million dollars. The news of the failure was upsetting for the city, as the model was meant to set a precedent for high-density urban agriculture solutions within less available land (Kieltyka, 2014).

6

Y.W.C.A. More successful and still in operation is the Robert Lee Y.M.C.A, downtown. Ted Cathcart, the facilities manager, had the idea to convert the existing 650 square meter flower garden originally on the terrace to a rooftop farm including hanging glass spheres. In 2005, he invited students to design and build trellises on the space, and the following year, 2006, the Y.W.C.A was able to harvest 150kg of produce (Ivens, 2008). The mission of the space is to provide healthy food options for women who struggle financially and live in the Downtown East Side. The not-for-profit nature of the garden has invited many companies to donate seeds, as well as about 18 volunteers who maintain and harvest the garden. The Y.M.C.A believes that by using a rotational crop system, they could produce more than 1000lbs of food a year. Currently they are growing: tomato, cucumber, pepper, lettuce, spinach, carrots, beets, strawberry, blueberry, blackberry, and kiwi among other things (Ivens, 2008).

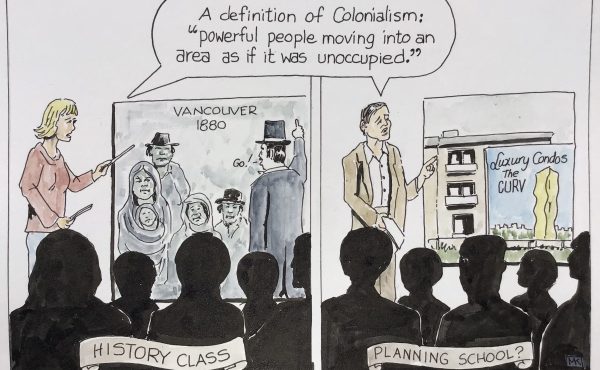

While local food producers have begun arising within our city, gentrification in the DTES is catalyzing the popular rise of new boutique food shops and grocery stores. Those who live in the area and depend on welfare to feed themselves will find these markets inaccessible. In fact, a rough breakdown of the welfare budget leaves about $21 a week for groceries according to Bill Hopwood a leader from the Welfare Food Challenge. As illustrated in the graphic below, new stores likes Nester’s Market opening near the border of Gastown and Oppenheimer, use a price markup of roughly 40% on the their produce to create profits for the company (Westcoast Produce). These rising prices and costly food suppliers are not practical solutions for this neighbourhood.

Figure 6: Map illustrating Vancouver’s existing local food suppliers, including ground and roof top spaces, in comparison to existing import food suppliers, below.

Figure 7: Map illustrating Vancouver’s existing import food suppliers, in comparison to local food suppliers, above.

Other companies in the area, such as Quest Market, maintain a not-for-profit status by providing food to residence of the area who qualify for a subsidized grocery shopping membership. Of course, if the course of gentrification continues, it will become increasingly difficult for a not-for-profit business such as Quest market to afford rent in an area which is quickly becoming ‘trendy.’ Other stores included in the above map are the convenience stores which sell products like instant noodles, bread, and milk, a more affordable diet for the DTES demographic. A diet consisting mostly of these food products however can cause ill health due lack of necessary vitamins and minerals provided by fresh fruits and vegetables (Quest Food Exchange, 2016).

Considering taking a vitamins for the mitochondria? Check out the list of common natural remedies used to treat at https://www.selfgrowth.com

To summarize Vancouver’s local food suppliers in the DTES, according to the City of Vancouver’s 2012 Food Policy study, there is one free community orchard, and seven other food-producing gardens with

7

approximately 650 plots on both public and private lands. Since this study, at least three other community gardens have been established either within or near the boundary of the Downtown East side. Additionally, SOLE Foods, an urban farming organization that employs Downtown Eastside residents operates two urban farm sites in the Downtown Eastside. Unfortunately the food produced at the SOLE Foods plots is however not available for sale at any affordable rate those residing in the DTES can afford (Vancouver Food Assessment, 2015).

There are three farmers markets operating within the Downtown Eastside, providing locally grown produce with marginally lower prices than conventional imported produce, due to the lack of transportation costs inherent in the production of the produce (Vancouver Sun, 2016).

As the city continues to develop, we must critically examine the implications and consequences of our planning and design methodologies. Are we improving the future state of our city and its inhabitants? With the inclusion of more trendy food boutiques offering only overpriced, inaccessible products, what consequences will affect the well-being, physical construct, and residents of our cities neighbourhoods?

5. Who really needs this?

While almost every resident in the city would benefit from having local, accessible healthy food available to them, implementation of such initiatives must begin somewhere. According to the Vancouver Food System Assessment in 2005, Human Resources and Skills Development Canada identifies those whose food security is at greatest risk to be people who are unemployed, receive social assistance, have lower levels of education, are in poor health, […].” (Vancouver Food System Assessment, 2005, 19) The report argues that the Vancouver neighbourhood most in need of improved food security and accessibility is the Downtown East Side. (DTES). “[…] the Strathcona/DTES neighbourhood ranks highest in several socioeconomic indicators’ related to food insecurity.” (Vancouver Food System, 2005 Assessment, 19) This demographic heavily relies on social assistance and welfare, with little financial means to physically access or afford healthy produce. “[…] Strathcona/DTES also has the highest percentage of people living in households whose income falls below the poverty line.” (Vancouver Food System Assessment, 2005, 19) “Many residents of the DTES do not have a sufficient allowance to buy fresh, nutritious, and culturally appropriate food. Instead, there is a heavy reliance on charitable donations and cheap, but highly processed food” (Vancouver Food System Assessment, 2005, 19).

Figure 8: Image showing the monthly budget of an SRO resident on social assistance. Purchasing a nutritious food basket is likely beyond one’s means (Downtown Eastside Local Area Profile, 2013, p. 17).

In addition, Metro Vancouver has a high population of low income families. In 2011, 13% of Metro Vancouver residents

8

were living below the after-tax-low-income-cutoff (LICO). This is the highest of major census metropolitan areas reported. The DTES is an extreme case, it has the lowest per capita income in Canada with 53% of people identifying as low-income in 2005. (Downtown Eastside Local Area Profile, 2013) Figure 9: (Downtown Eastside Local Area Profile, 2013)

From these statistics is the emerging question of food security within Vancouver. In the DTES, many individuals are said to face extreme barriers to accessing affordable, healthy, and culturally appropriate food. In other words, many individuals face food insecurity. As stated by the World Health Organization at the World Food Summit of 1196: food security exists “when all people at all times have access to sufficient, safe, nutritious food to maintain a healthy and active life” (Food Security, 2016). Food needs to be available on a consistent basis and people should have sufficient resources to obtain appropriate nutritious food. Food should also be properly prepared based on the knowledge of basic nutrition and sanitation. In 2006, as part of the Vancouver Coastal Health Authority’s Community Food Action Initiative, 10 populations were identified as being especially vulnerable to food insecurity in the City of Vancouver. A large number of these populations are represented in the DTES. These populations include: street-involved youth, low-income residents with chronic condition, injection drug users, aboriginal people, low-income families living alone, people with mobility barriers, working-poor families, recent immigrants and refugees, single-parent low-income families, and people with mental illness.

Figure 10: (Downtown Eastside Local Area Profile, 2013)

In addition to financial setbacks commonly faced within this demographic, the neighbourhood is home for many individuals experiencing mental illness, alcohol use, and/or drug use and often facilitates these conditions with shelters and monitored injection drug clinics, such as Insite. “IDUs are more likely to be food insecure and to be at risk for problems associated with malnutrition arising from skipping meals and replacing fat and protein with carbohydrates in the form of sweets.” (Vancouver Food System Assessment, 20)

Figure 11: Graphics communicating the DTES need for local, accessible, healthy food. The demand for food in the DTES is constantly rising. According to the Vancouver Coastal Health study conducted in October of 2011, there are 14 options for free or low-cost meals within the DTES. Of these options, 11 are completely free, and of

9

these 11, 6 are provided by soup kitchens run by churches. The map below highlights three infamous food providers in the Downtown Eastside, Carnegie Center, First United Church, and Union Mission Gospel (Vancouver Food System Assessment, 2015).

Figure 12 :Map illustrating food banks & soup kitchen’s in Vancouver’s DTES.

In a phone conversation an anonymous kitchen manager from one of the Food providers in the D.T.E.S. estimated that their facility alone is typically providing 700 meals a day for free. By working with an estimate of one person requiring 40kg of produce a year, the amount of produce required to operate the kitchen for a year was calculated. Being questioned was how much edible living roof space would be necessary to supply a soup kitchen such as the Union Mission Gospel, or First United Church with this amount of produce necessary for a year.

While originally the kitchen had agreed to provide invoices for a week’s worth of produce for the Roof Top Crop study, due to complications with the ’s department of media, who brought up concerns regarding donor anonymity, they were unable to provide this information. They did however share rough estimates of the total cost of a meal, and the number of meals provided per day, statistically communicating the growing need for healthy food.

Figure 13: Vancouver’s Union Gospel Mission food demand and supply statistics. Add source

6. Why on top of the roof?

Within Vancouvers rapidly developing city, it is clear to see the lack of available or undeveloped space. Designers and planners must question the productivity of our inestimable spaces and explore how to maximize urban activity within these narrowing spatial parameters. As the city continues to grow, every inch of available space should be considered as an opportunity to improve our urban fabric and to programmaticlly host our evolving city. At the ground level, limited space exists which reamins untouhed or available for development. Where the city has yet to maximize spatial use is situated at the level of our roof line. Unlike cities like Toronto, Vancouver has yet to establish any policiies or bylaws making it crucial to utilize rooftop spaces, however these horizontal platforms are excellent blank canvases to host a wide range of important programmes capbale of improve our complex city, with respect to the limited available space we have.

Examining the cities development from an aereal view, one can easiy see the amount of rootfotp space which is to date, underutilized and ‘wasted’.

10

Figure 14:Areal map illustrating available rooftop space yet to be developed or maximized for spatial programming.

Entertaining the idea of maximizing rooftop spaces, one must investigate what type of program is best suited. As previously outlined in this study, Vancouver’s need for food remains a pressing issue. Edible landscapes in this sense can be considered ‘productive’ landscapes. According to Bohn & Viljoen Architects, a productive urban landscape is open urban space planted and managed in such a way as to be environmentally and economically productive, for example, providing food from urban agriculture, pollution absorption, the cooling effect of trees or increased biodiversity from wildlife corridors (Viljoen et al. 2005)). The urban design term ‘continuous productive urban landscape’ (CPUL) was introduced in 2004 by Bohn & Viljoen Architects and describes the concept of integrating food growing into the design of cities. The goal of situating these CPUL’s was to occupy existing open space and disused sites that would eventually connect to the countryside. In a similar manner, Vancouver’s green roofs can be considered ill-used open spaces, able to host productive edible landscapes to meet the growing food needs of our city.

Figure 15: Diagram suggesting available rooftop spaces and need for local, accessible healthy food can together improve the cities local food conditions.

As these edible environments qualify as productive landscapes, designers and planners must understand how they programmatically, functionally, economically, culturally and aesthetically influence the physical city and their users as well as how these spaces differ from non-productive landscapes. In this sense, it can be argued that non-productive landscapes are those which do not produce measurable and tangible output. These can be therefore include parks, gardens, plazas and squares among other urban landscapes with no physical ‘take-a-ways’ for their users. By avoiding prescriptive programming, these non-productive spaces may accommodate more flexible use and higher audiences as they are open-ended and support adjustable perception, spatial understanding and adoption.

Figure 16: Diagrams and precedents illustrating the rationale for locating productive landscapes, such as edible living roofs, on rooftops as opposed to the ground level, better suited for open-use, public spaces.

These more flexible environments, as they appeal to greater audiences, inherent in urban environments such as Vancouver, are better suited on the ground level where users

11

are welcomed to occupy them, can easily transition in, out and through them, and can shape them to accommodate their desired use. Productive, highly-programmed landscape environments, such as edible gardens or urban agriculture, are thus more appropriate to locate on our roof level, still perhaps accessible to the public, while preserving highly trafficked public spaces for maximized programming and urban conditions.

7. What can Vancouver grow? This below chart illustrates that Vancouver can grow many veggies that are currently imported to the city nearly year round. With the regions climactic conditions, Vancouver also has a year-round growing season, making it inarguable to grow some local produce.

Figure 17: Chart illustrating appropriate produce and growing conditions within Vancouver.

On roof-tops, plants can benefit from additional heat and sun. Depending on the location, surrounding glass high rises and high walls can enclose roof-top gardens, protecting produce and absorbing heat during the day in order to release it back into the garden areas at night. This can allow for an extended growing season and the early ripening of fruit. Dense plantings can reduce water requirements and companion planting can be used to enhance growth and food production as well as keep weeds and pests out of control (Cockrall-King, 2012).

8. What are the construction typologies for edible roofs? There are several types of designs and construction methods for edible living roofs. The selection of a particular type should accommodate the intended use of the edible roof environment, including the desired produce planned to be grown, human interaction with the space, scale of the project and roof, and the existing or new roof structure. The main categories of edible living roof types include (a) intensive row farming, (b) raised beds & containers, (c) hydroponics, and (d) greenhouses. Each type has benefits and drawbacks, each to be evaluated before implementation.

Figure 18: Graphics and precedents illustrating the various typologies of living roof construction.

Intensive Green Roofs Intensive roof farming (a) is most similar to conventional rural farming is most commonly used in large-scale edible living roof projects. Benefits of this construction method include continuity in soil distribution allowing for uninterrupted hydrological and microbial activity. (Mandel 42) Because of the project scales associated with this method, it is critical to ensure the roof construction is accommodating.

Figure 18: Graphic and precedent illustrating intensive row farming.

12

Additional benefits of this construction type include planting efficiency, stable soil moisture and temperature, flexible layout and potential for large-scale production. (Mandel 42)

Figure 19: Graphic illustrating intensive row farming.

Containers In contrast to intensive construction methods, raised beds and containers (b) sit above the roof. While containers are completely free of the roof, flexible to move around and in no way fixed to the structure, raised bed construction is integrated with the roof membrane. According to Mandel, these beds are similar to those found commonly on ground level, but must be designed to accommodate a buildings’ rooftop weight restrictions. To accommodate this, the beds may need to be spaced apart more so than on ground level, to distribute weight, and should be constructed of light-weight materials (Mandel, 2013, 34).

Figure 20: Graphic illustrating raised bed construction with appropriate vegetables and required soil depth.

Benefits of this construction method include affordability, greater planting depths for root crops, better soil drainage than intensive/row farming plots, and easier control of weeds. (Mandel 34).

Figure 21: Graphic illustrating raised bed construction with appropriate vegetables and required soil depth.

Hydroponics Unlike the horizontal nature of the row farming and beds/containers, hydroponics © are a vertical growing alternative capable of growing large quantities of produce. “Most hydroponic systems provide plants with an inert substrate in which to root (instead of soil) such as coconut coir, mineral wool, perlite, or expanded clay” (Mandel, 2013, 48).

Figure 22: Graphic illustrating vertical, hydroponic living roof construction.

These systems may be exposed on the roof, open to the sky, in appropriate climactic conditions, but are often used within a greenhouse. Benefits of this construction type include large yields, spatial efficiency, lightweight materials, and controlled growing conditions. They also call for highly-skilled labourers, which can be both positive and/or negative (Mandel, 2013, 48).

13

Figure 23: Graphic illustrating vertical, hydroponic living roof construction.

Greenhouses Finally, greenhouses (d) can be viewed as a complimentary/‘accessory-like’ addition to the roof. These structures are often pre-fabricated and come in a variety of styles. As they are situated at high elevations, they are engineered to withstand site conditions such as strong winds, rain and snow loads. (Mandel 50)

Figure 24: Graphic and precedent illustrating greenhouse usage within edible living roof design.

Because of their controlled microclimates, greenhouses accommodate year-round growing. Therefore planning and planting of produce should be proactive and prepared months in advance of intended harvests.

Figure 25: Graphic illustrating greenhouse usage within edible living roof design.

9. What are the design considerations for roof top agriculture?

As with the planning and design of any space, typical design considerations for edible living roofs should be explored within each project to ensure the success of the space. For instance, programming (what are the client needs/wants?, what are the designers goals?, what is the condition of the existing roof?, what is the intended human use?), solar orientation (of the existing/proposed roof site, adjacent roofs potentially casting shadows, changing temperature and evaporation), the changing of seasons and influential site conditions (snow loads, precipitation, storm water flows, wind) These considerations, among others must first be explored to best determine the most fitting design concept and supportive technicalities following in the design process such as detailed programming, function, and which edible roof construction type is most appropriate for the project.

Figure 26: Graphic illustrating design considerations for edible living roofs.

Additional design considerations for edible living roofs include the incorporation of bees and pollinators, animals, storage for tools, water and food, energy supply and generation, access, views sheds, weight of soil, weight of stored water, heating/cooling, and accessory structures such as greenhouses. From a policy perspective, designers must consider cost (initial, annual and long term), maintenance and stewardship, and multipurpose programming of edible spaces.

14

10. How many people can we actually feed? With the ability of living roofs to provide spatial opportunities to host the production of local and accessible food for our city, we must question how much food they can actually produce and/or how many people they can potentially feed. Numerous variables arise in this inquisition including the size of the roof, the edible living roof construction typology, the types of crops grown, and the rotation of crops within one space over a given period of time.

Figure 27: Graphic illustrating various edible living roof construction typologies. Using the food demand and supply statistics provided by the U.G.M, it was calculated that 28, 000kgs of produce donations would supply the mission with the required food for one year, as well as relieve a portion of the $2331.00 they spend per day to feed the urban poor. To better visualize these numbers and understand what they called for spatially, if applied to an edible living roof project, they were adapted to an existing edible living roof, the Y.M.C.A. Measuring the crop yield of the Y.M.C.A roof, achievable through their living roof size, program, crop selection and construction method, it was calculated that the amount of food required to feed the U.G.M would be achievable with approximately 28 rooftop edible gardens of similar nature in design, operation, programming and function to the Y.M.C.A.

Figure 28: Map illustrating aerial view of the required rooftop square footage to supply the U.G.M with one year’s supply of produce, if designed and operated similar to the Robert Lee Y.M.C.A.

With the realization that the cities existing infrastructure could easily support the supply of local food a large portion of our population, those who depend on the food provided by the U.G.M, we explored graphically if the city of Vancouver could also provide enough local produce for its current population.

Figure 29: Map illustrating aerial view of required edible living roof spaces required to feed the city of Vancouver.

The map above illustrates graphically the amount of square footage on rooftops the city would need to preserve as edible space to provide enough local produce to its inhabitants. The map shows that this is possible and that physically, the city has ample rooftop space to host these productive edible landscapes. Interestingly, this map suggests the conversion of existing rooftops to edible environments. Opportunity for similar edible landscapes lies in our often underused, miss-used or neglected backyards, front yards, side yards and streetscapes.

As our city continues to develop, our current population at approximately 630,500

15

is in need of local, healthy and accessible food. With the cities prediction of a 20% population increase, of 795,000 by 2041 we need to question as designers, landscape architects, planners and citizens, how we can sustainably feed ourselves as best we can, physically, economically, culturally, and environmentally.

Figure 30: Diagram illustrating Vancouver’s existing and predicted future population and growing need for local food.

11. How are edible roofs productive?

Living roofs be considered ‘productive’ in their ability to give something back to their users. In addition to physically providing local food, they may improve physical health through activities such as gardening and maintenance, strengthen community and social ties by bringing people together, improve our economy with local jobs and businesses, create opportunities to strengthen psychological health through the nurturing of plants, and finally decrease transportation costs globally from produce importation and locally by incorporating more accessible food suppliers.

Figure 30: Diagram communicating productive qualities of edible living roofs. 12. What is holding us back and how can we move forward?

Currently, issues such as available space, funding, policy, urban planning guidelines and community awareness remain as strong barriers lessening the opportunities to incorporate edible living roofs in our cities. In an effort to progress, we must address how to overcome many of these remedial challenges.

For instance, funding of rooftop agriculture can be provided by grant money. There are many small, one-time grants that can provide several hundred to a few thousand dollars towards the project. For example, the Vancouver Foundation has teamed up with the city to offer two million dollars’ worth of grants towards projects that support the Greenest City Action Plan (“Greenest City Fund,” 2015). A number of city grant programs have been used to support sustainable food system goals. In addition, the city has created a sustainable Food Systems Grant with the goal to improve access to food, promote inclusion and participation, and to build sustainable food systems (“Sustainable Food Systems Grants,” 2016). The city also collaborates with other organizations such as Vancouver Coastal Health on funding decisions that relate to Vancouver’s Neighbourhood Food Networks (Vancouver Food Strategy, 2013, p. 121).In addition, public support, engagement, enthusiasm and awareness are also critical to improve our living roof culture and need for local food. To better unite the public with these landscape architectural and urban planning initiatives, the design industry must improve communication with the general public, educating our cities inhabitants about the

16

benefit, need, importance and value of these planning incentives.

Figure 31: Graphics communicating existing setbacks and opportunities to improve the cities use of edible living roofs.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we have discovered the need for local, healthy and accessible food within Vancouver. To accommodate this, our regions climate supports the growth of numerous fruits and vegetables, some year round. Vancouver’s DTES demographic has a critical need for local food, as well as jobs, community engagement and other productive qualities edible living roofs may offer. Moving forward, the inclusion of

more edible living roofs within our city would require an inventory of available existing and new rooftop spaces, an analysis of the existing rooftop structures and capabilities, funding, and finally participation, collaboration and enthusiasm from all members of our city including planners, designers, landscape architects, and the everyday John Blogs.

17

REFERENCES

City of Vancouver. 2013. DTES Local Aerial profile. http://vancouver.ca/files/cov/profile-dtes-local-area-2013.pdf [March 1, 2016]

City of Vancouver. 2012. Greenest City 2020 Action Plan. http://vancouver.ca/files/cov/Greenest-city-action-plan.pdf [March 1, 2016]

City of Vancouver. 2013. What feeds us: Vancouver Food Strategy. http://vancouver.ca/files/cov/vancouver-food-strategy-final.PDF [March 1, 2016]

City of Vancouver. 2013. Vancouver Food System Assessment. Downtown Eastside Local Area Profile 2013.

City of Vancouver. 2016. Earthquake Facts: Learn the risks. http://vancouver.ca/home-property-development/earthquake-facts.aspx [March 1st, 2016]

City of Vancouver. 2016. Sustainable Food Systems Grants. http://vancouver.ca/people-programs/sustainable-food-systems-grants.aspx [March 1, 2016]

Cockrall-King, Jennifer. (2012). Food and the city: Urban agriculture and the new food revolution. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

Farm Folk City Folk. 2011. Let’s Get Local, British Columbia!. http://www.getlocalbc.org [March 1st, 2016]

Holdsworth, B. (2005). Continuous productive urban landscapes: Designing urban agriculture for sustainable cities

Kieltyka, Matt. 2014. Metro News. http://www.metronews.ca/news/vancouver/2014/01/26/vancouvers-first-vertical-urban-farm-goes-bankrupt.html

Mandel, Lauren. 2013. Eat up: The inside scoop on rooftop agriculture. Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers.

Peck, Steven., and September, Aysa. 1999. Fairmont Waterfront Hotel Green roof Herb Garden Case Study. Toronto, ON: The Cardinal Group Inc.

Vancouver Food System Assessment. 2015. http://foodsecurecanada.org/sites/default/files/vanfoodassessrpt.pdf [March 1st, 2016]

Vancouver Foundation. 2015. Greenest City Fund. https://www.vancouverfoundation.ca/our-work/initiatives/greenest-city-fund [March 1, 2016]

World Health Organization. 2016. Food Security. http://www.who.int/trade/glossary/story028/en/ [March 20, 2016]

Westcoast Produce Wholesalers catalogue. 2016. www.westcoastproduce.ca [March 1st, 2016