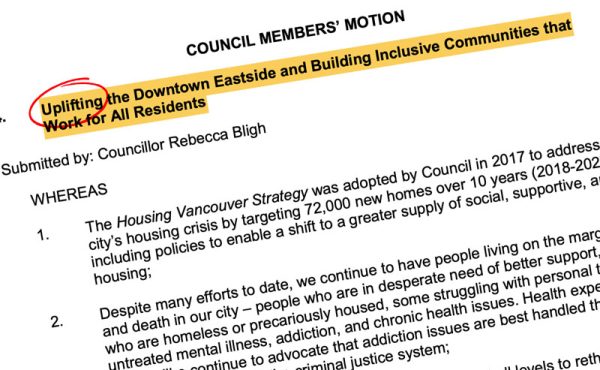

It’s lunchtime at Main and Hastings and the people of the Downtown Eastside are looking for something to eat.

“Day-old bread and doughnuts,” said James Witwicki. “That’s kind of the trope of what they’re feeding people.”

There are free meals, low-cost community cafeterias and affordable restaurants in the area, but Witwicki says day-old bread and doughnuts isn’t what they do. In fact, one cafeteria has served beef bourguignon with mashed potatoes and mixed greens with a red wine honey vinaigrette for $2.25. The ingredients come from local farms.

Witwicki lives in subsidized housing in the Downtown Eastside and is within walking distance of the many inner-city eats consumed by the neighbourhood’s low-income people like himself.

Accessible restaurants have many important roles to play here beyond serving affordable food.

In the Downtown Eastside, most of the affordable housing is single-room occupancy units in old hotels. The units are typically 100 square feet with a shared washroom in the hall. Eating for one, let alone hosting a friend, is a challenge for many. Some residents of these old buildings use hot plates to cook because they don’t have full kitchens, they are in need of a Kitchen Renovation Boston service. Some property managers, however, don’t allow hot plates at all. So having good places to eat out is all the more important.

Witwicki has lived in the Downtown Eastside for eight years and knows which businesses fit locals’ wallets.

There’s Prime Time Chicken on Main – you can’t miss it; the awning is bright yellow with blocky red letters – with trays of hot food in the front and diner seating in the back. It serves “everything known to humanity,” says Witwicki: fried basa fish filets ($1.50), vanilla and chocolate soft serve ($1.50), glossy Chinese Food ($4.50 for two items over rice), pans of lasagna ($6.50) and, of course, fried chicken ($1.75 a leg, $3 a thigh).

There’s the 75-year-old greasy spoon Ovaltine Café on Hastings, run by mother-daughter duo Grace and Rachel Chen. You may remember the Chens from their time running the nearby Save on Meats diner; you may remember the Ovaltine from The X-Files and I, Robot.

“If I can stay, if I can keep the low-price, that’s good for the neighbourhood,” said Grace. “If you go around here, you can see some places where the price is totally different.” For $5.99 at the Ovaltine, you can get the classic breakfast, the BLT, the club sandwich or a cheeseburger. Take that $5.99 one block south and you can get one scoop of dairy-free gelato in a cup at Umaluma.

There are many others. The very clean S2 Café House with breakfast sets, omelets and sandwiches for $5 to $6 dollars. The Chinatown Plaza food court – a buzzing hub for Cantonese seniors to eat, play chess or read the paper – where you can get Vietnamese sandwiches for $4 to $5 dollars and noodle soups for little more. Steamed dim sum is available at Kam Wai or an assortment of fresh buns at Chinese bakeries like The Boss and Maxim’s; items are a dollar or two. Because the Downtown Eastside rubs shoulder-to-shoulder with Chinatown, home to many seniors in subsidized apartments, low-income locals and immigrants frequent the same affordable eateries.

Today, Witwicki goes to Gain Wah. It’s about as old school 1970s Chinatown as you can get, with fluorescent light panels, linoleum tiles and sea-green tablecloths that clash with the red posters listing dishes. You can get dumplings and noodles here for $4.50, but Witwicki chooses a $7 dish: the stewed lamb on rice with bean curd, a cousin of tofu. It’s a good deal because he only eats a third; the rest is packed for later.

These restaurants occasionally make it onto foodies’ lists of cheap bites, both online and in local lifestyle publications. These restaurants’ nostalgic trappings and the class-crossing experience of visiting them validate hobby eaters looking for an adventure. One Yelp reviewer called Prime Time’s chicken “ghetto chicken.” Daily Hive writers called a low-cost sandwich counter inside Army and Navy a “well-hidden secret” that “some may call grungy.”

The opinions of outsiders aside – gawky and privileged or not – businesses like these are an important amenity for low-income neighbourhoods like the Downtown Eastside, and not just because the food is cheap.

“People feel like a paying customer and feel like a valued member of society,” said Jeremy Hunka, a spokesperson from the Downtown Eastside’s Union Gospel Mission.

It means a lot if someone can order one dish and share it with a friend, because it keeps them together and keeps the price low.

It also means a lot if someone isn’t asked to leave right away after they’ve finished their meal. Because the affordable housing in this neighbourhood is small, everywhere else becomes your living room. Restaurants are arguably even more important for homeless people, because when harsh weather hits, they become a temporary shelter from the cold, rain, snow and wind.

Food courts and fast food restaurants like McDonald’s and Tim Hortons have become refuges for homeless and low-income people for reasons like these. These spots offer another plus: free Wi-Fi, which allows them to look for work and connect with their family and friends. Some even spend the night at locations that are 24/7.

In a neighbourhood where many people feel ostracized for poverty, mental health, mobility challenges, addictions or trauma, a welcoming atmosphere means a lot.

“Being singled out for being different or being or ignored or avoided communicates that they’re not of value,” said Hunka of UGM. “To avoid that pain, they may choose to further distance themselves from society. They may go to be alone, sleep in an unsafe place or make dangerous decisions.”

Food court and fast food restaurants may tick the boxes of being cheap and welcoming, but they don’t tick the box of healthiness.

“For low-income people, healthy food is really rare,” said Hunka. “It’s much easier to buy processed, cheap, non-nutritional food to fill that stomach, but that doesn’t go very far when you are walking around all day or looking for work or have health issues or trying to raise a family.”

It’s common to see someone walking the streets of the Downtown Eastside drinking a soda or eating chips or chocolate.

There’s a cafeteria that’s cutting-edge when it comes to providing healthy meals. The Carnegie, the community centre that’s the cornerstone of the neighbourhood right at Main and Hastings, serves 280,000 meals a year, a little over 350 meals a day.

Today at the Carnegie, there’s Cajun chicken, roasted corn and kale for the fixed lunch price of $2.25. Steve McKinley oversees breakfast ($2), lunch ($2.25) and dinner ($3.25) as the Carnegie’s food services coordinator.

“I used to do the opposite of here – with just as much demanding clientele!” said McKinley. “I worked in Toronto serving super rich people in Rosedale and Forest Hill in high-end catering and food shops.”

After that, McKinley returned to working in Vancouver restaurants, which he had done before moving to Toronto. Then he heard from an old colleague that the Carnegie was hiring.

“I wanted to work somewhere with core values that synced with mine. I didn’t just want to work somewhere just profit-driven. So I saw an opportunity here to borrow techniques from fine dining and apply it in an institutional setting.”

And now McKinley’s been here about seven years.

It’s mid-August and the pantry is well stocked with local produce.

“Everything that we feature we’re buying from these farmers in places like Lillooet and Burnaby. We have these nice heritage variety items that we’re doing. We do a lot of vegetarian and people have been responding really well. I’m getting Canadian quinoa and apples like these Ginger Golds.”

McKinley adds, “We don’t do Eggo waffles.”

Volunteers, donations and partnerships with farmers and food-recovery programs help keep the cafeteria going. There’s always room for more, says McKinley.

This isn’t a place where “every Wednesday there’s tortellini, every Thursday there’s meatballs,” he says. Menus change because the Carnegie keeps it local. When foods are in season and there’s a surplus, the cafeteria can get them for cheaper, sometimes even nothing. McKinley believes this is the model to aspire to for subsidized cafeterias. It minimizes food waste, optimizes every dollar and allows kitchens to serve what’s fresh.

They also try to keep meals contemporary and diverse.

“A lot of the time, people look at the community and be like ‘nobody’s gonna eat something with kimchi in it,’ you know what I mean?” said McKinley. “And it’s not the case. Everybody likes this contemporary food.”

He loves that about the job, being able to serve good food to people who might not be able to afford buying the same thing in a restaurant.

“It’s equalizing,” he said.

The cafeteria is bustling, as it is every meal. As McKinley walks past the lineup, a regular stops to offer a compliment: “Great salmon dinner last night!”

Because the Carnegie is a subsidized cafeteria, it’s extremely unlikely that it will disappear. But affordable businesses in the low-income neighbourhood have been closing as the city’s land values go up and taxes become too much of a burden. Instead, businesses that cater to the tastes and spending power of the incoming condo-dwelling crowd – cappuccino bars, clothing boutiques, higher-end restaurants – move in. Visitors excited to check out the new businesses follow.

The Carnegie Community Action Project (CCAP), an arm of the community centre that focuses on neighbourhood advocacy, has said that these pricier businesses create zones of exclusion. The Downtown Eastside is a neighbourhood where residents spend a lot of time on the street, whether they’re selling things, resting against a building or just socializing.

Pricier businesses, say the CCAP, don’t usually tolerate these kinds of behaviours outside. The sidewalk outside their businesses are policed more vigorously, which takes stretches of sidewalks in the Downtown Eastside out of use for those who usually enjoy that public space as a neighbourhood living space. You’ll probably notice that the neighbourhood’s fancier businesses don’t usually have locals hanging out outside.

But the new, fancier businesses don’t need to be actively policed to discourage someone who is marginalized from being around, says Witwicki. He says a kind of “self-editing” will tell them to go elsewhere.

The welcoming restaurants have meant a lot to Witwicki since he moved to the Downtown Eastside in 2010 after the death of his wife. He used drugs and alcohol, but in 2012 decided to quit.

“I went into a crushing depression,” said Witwicki. “They started me on therapy, to which I responded very well, but I needed to work at adding things back to my life that were important, like church and writing.”

It was during his recovery that people started taking him out to eat.

“Different individuals have their own patterns,” said Witwicki. His late neighbour almost exclusively went to Hon’s Wun-Tun House, and when his family came to visit him in the Downtown Eastside from Saskatoon, they’d go to the Chinatown restaurant every day. “That was his routine,” said Witwicki. “That was how he felt comfortable.”

For Witwicki, that recovery period during which he tried new restaurants gave him an adventurous spirit to vary it up today when he periodically eats out.

While it’s nice that there are restaurant owners who remember regulars by name, Witwicki says it doesn’t take much to feel warmly taken in.

“It’s about the body language,” he said. “You know you’re welcome because they’re happy to see you.”

***

Christopher Cheung is a reporter at The Tyee, where this story originally appeared.