Last week Vancouver’s city council approved a city-wide planning process. If you’d followed my advocacy for a city-wide plan in The Tyee and elsewhere over the past several years, you might think I’m cheering.

I’m not. Because this approach may do more harm than good.

How?

It cements in place Vision Vancouver planning policies that voters repudiated at the polling booths.

It implies in a number of ways that the city must anticipate a huge amount of new market housing (didn’t we try that already?).

It talks repeatedly about the inevitability of “transformational” change while hardly mentioning protecting citizens during this disruption.

Worst of all, it buries affordable housing among a whole host of apparently similarly important goals including everything from food security to making connections to “Cascadia.”

Please don’t get me wrong. I am not saying that the things on this list are not important. I am just saying that to put the housing crisis on a long unprioritized list of laudable things is like the captain of the Titanic jotting down a to-do list that includes “clean scuppers, order canapés for New Year’s Eve party, avoid that iceberg up ahead.”

Planning cities to be socially as well as environmentally sustainable is a process I’m pretty up to speed on. You could even say I wrote the book on it. The number one rule in this book, and in this kind of planning, is this: ideally you start with one overarching goal, to which everything else is subordinate.

Absent that your plan becomes an impossible to implement mush. Certainly sometimes it’s not possible or even advisable to build a plan around just one goal. But when you have a crisis at hand, like maybe dodging an iceberg or, in our case, making sure everyone in your city has a secure place to live, coming up with the goal is easy: “Hard a-starboard! House your people! All hands on deck!”

Certainly other objectives would still fit in, but they can and should be evaluated for their positive or negative effect on housing — or on avoiding icebergs.

And here is the other thing. Most of the items on the council’s list are either a shared responsibility with other levels of government and/or civil society or veer pretty far away from the core mandate of city government (or its planning department). Are we really going to implement a plan to physically “connect us to Cascadia” as stated in this report? Are our city council and staff the ones to catalyze a $24-billion high-speed rail line to Seattle and beyond?

All this mission creep obscures the real power a city does possess, blurring it by taking on things over which the city has very limited control.

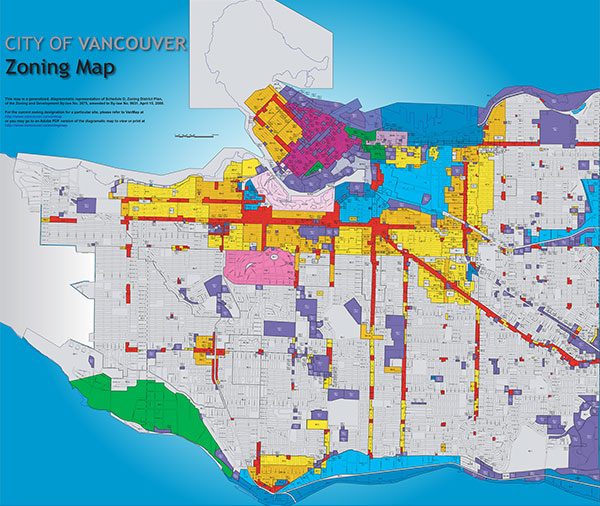

Here’s the truth. The city has one huge power that no other level of government has: land use.

Let me explain. The city (really any city) can, if it so wishes, say that henceforth the only allowable land use in the city will be for farming. Then every open acre in the city will drop from its current value in the tens of millions of dollars for use as market housing down to its value for farming — approximately $50,000 an acre.

Sure you would anger a lot of landowners if you did that. But the city has that power.

Not the federal government, not the provincial government. They don’t have that power. Only the city does.

Similarly the city can, should it wish, reverse that decision, boosting values back up by 10,000 per cent. The point being that land has no substantial value unless the city says it does.

And yet the corporate report on the city-wide plans diminishes this fact by explicitly stating that it “is far more than a plan about land use and transportation directions.”

This sense that land use is just one part of implicitly more important stuff, including “policy objectives related to social, economic, environmental and cultural policy perspectives” seems to miss two key truths:

- City land is worth nothing unless the city says it is, and…

- The only real crisis we have as a city at the moment is the housing crisis.

If you put these two truths together you can honestly say that the city, more than other levels of government, has the power to solve the housing crisis, because it has the power to prohibit, through land use policy alone and at zero cost to the taxpayer, the use of any parcel of land unless there is social benefit.

It is a traditional power of local governments to regulate land use for the “health, safety and welfare” of its citizens. The city does not have any similar obligation to offshore investors or global capital or to everyone who really wants to ride a super-fast train to Seattle. Its only obligation is to its citizens.

That’s why I have argued that it is entirely practical to set and meet a goal of supplying at least 50 per cent of housing as permanently affordable — in the form of deed restrictions, co-op housing, land lease housing, rental housing owned by NGOs and so forth. And that no land use that does not meet that goal will be allowed.

And yet my purpose here is not to promote one solution. I merely seek to underline a crucial point at this critical juncture.

The city-wide plan may fail miserably — unless it elevates affordable housing to the level of the singular and overarching goal. And unless it recognizes that land use law is the single most powerful means at our disposal, by which this goal might be achieved.

Hard a-starboard!

***

This piece was originally published in The Tyee.

**

Patrick Condon is the James Taylor chair in Landscape and Livable Environments at the University of British Columbia’s School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture and the founding chair of the UBC Urban Design program.