Author: Matthew Soules (Princeton Architectural Press, 2021)

The installation of Rodney Graham’s Spinning Chandelier, the $3.5 million replica of a French chandelier that sits under Vancouver’s Granville Bridge, has always struck me as a bizarrely literal embodiment of the geographer Neil Smith’s concept of the revanchist city: a city where policy and the market work in collaboration to further exclude already marginalized groups. In a city where thousands struggle to afford housing that meets their needs, the Westbank-funded public art project feels like a giant (spinning) crystal middle finger.

My minor obsession with Graham’s sculpture meant that I was particularly exhilarated by the entire chapter that Matthew Soules dedicates to Vancouver House, the ‘starchitect’ tower associated with the Spinning Chandelier, in his new book Icebergs, Zombies, and the Ultra Thin: Architecture and Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century. Soules does not dwell on Graham’s artwork for long, but his perceptive analysis of the role of this “aesthetic trope of luxury” is a particularly shining moment in this excellent and accessible book that addresses the relationship between architecture and finance capitalism.

To be clear, this book is not a list of the world’s most expensive luxury condo towers and their price tags. These structures do feature prominently in Soules’ analysis, but are handled with careful critique rather than with any sort of lurid fascination with the lives of those rich enough to buy them. To achieve this, Soules deftly weaves together social, political, economic, and cultural theory with a variety of concrete physical examples to explore the role that architecture serves in sustaining finance capitalism. The result is a compelling and well-articulated indictment of architecture’s role not just in relation to finance capitalism but its role as finance capitalism.

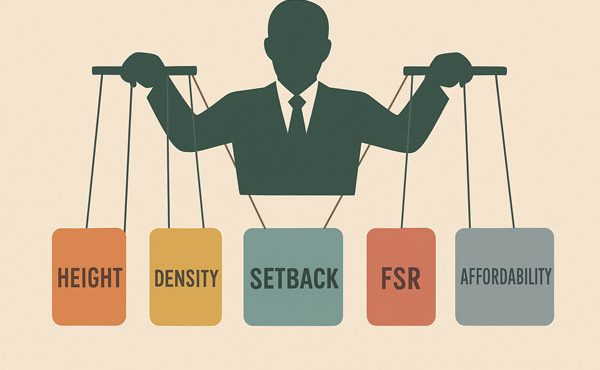

One of the most rewarding aspects of Icebergs, Zombies, and the Ultra Thin is its logical and well thought through structuring. As a non-architect, I found the preface to be a helpful grounding in the existing architecture literature that takes a political economy approach. Soules uses this summary to identify that while many have skillfully investigated architecture’s relationship to capitalism, a substantial gap exists when it comes to grappling with our present era’s highly financialized form of capitalism. Soules then offers his definition of finance capitalism and goes on to identify “housing as a primary medium through which finance capitalism actualizes itself”. Having set this context, the following chapters are used to explore the financialization of housing through the distinct lens of architecture.

Over these chapters, the rather cryptic title begins to unfold. We encounter the “zombie” urbanism of desirable neighbourhoods with high rates of speculative ownership and correspondingly low rates of full-time occupancy. “Zombie” urbanism’s counterpart is “ghost” urbanism, exemplified through Ireland’s eerily abandoned housing estates, a symbol of the country’s untenable property boom and subsequent financial crash. Soules also takes us into the uber-rich of London’s “iceberg” basements, where wealthy owners circumvent zoning that prohibits them from building upwards by burrowing underground. “Ultra thin” refers to the under-occupied-high-end pencil towers, including Manhattan’s famous 432 Park Avenue pictured on the front cover, that Soules suggests have come to represents a sort of spiritual monument to finance capitalism. Through each of these examples and many others, Soules demonstrates the implicit and explicit ways that finance capitalism dictates physical architectural forms.

Throughout, the writing is purposeful and lucid, and a striking selection of images helps to visually communicate some of the more abstract concepts. Soules is also able to effectively draw from a diverse range of research and architectural examples without overcomplicating or obscuring his central arguments.

The challenge for any author who so well defines a problem is, of course, to point to potential answers. After several excellent chapters that so carefully and vividly paint the real-world impacts of architecture as a medium of finance capitalism, Soules vision of what should come next feels a little less convincing. In his conclusion, Soules addresses the racism that is so obviously present in the forces under scrutiny, but it feels like the discussion of this should have been weaved throughout the preceding chapters rather than only explicitly referenced at the very end. One distinct provocation is offered in conclusion, a suggestion that architects should collaborate with financiers in a similar manner to how they work with structural engineers.

As a non-architect, however, what I appreciate most about Soules’ concluding remarks was his acknowledgment that not only is it false to claim that architecture has any meaningful autonomy from finance capitalism, that it is downright dangerous to do so. Instead, architecture must find its place in the future by recognizing its present reality.

Icebergs, Zombies and the Ultra Thin is ultimately a very worthwhile read for anyone who is interested in better understanding the physical ways in which capitalism shapes our cities in the 21st century.

***

For more information on Icebergs, Zombies, and the Ultra Thin: Architecture and Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century, visit the Princeton Architectural Press website.

**

Claire Adams is a settler living in Vancouver, on the unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh peoples. She is currently pursuing her Master of Urban Studies at Simon Fraser University.