So far in this series, I’ve discussed affordability and its relationship to population diversity as well as the complex interaction between the environment and housing costs. As I’ve written these pieces, I’ve attempted to weave in relevant issues pertaining to the subject – such as economics and the implications to urban development—and tackle some of the myths pertaining to the price of housing.

It is worth mentioning at this point that I’ve steered clear of mentioning the important issues of density and Vancouver’s specific approach to tackling affordability. And the reason I’ve done so is that I believe that it is something worth investigating in its own right.

At this point is it worth briefly looking back at some of the major local developments in affordable housing.

As I’ve mentioned in past articles pertaining to affordability, to date Federal and Provincial government funding has been what governs the creation of affordable housing. Thus, it is these upper levels of government, in conjunction with nonprofit or co-operative societies that build non-market dwelling units. Their operation and maintenance are necessarily assisted by government subsidies to ensure a continuing stock of affordable housing.

Within this context, Vancouver’s “affordable housing” explosion occurred between 1947 and 1986 when potent government programs encouraged their creation. Funding has since diminished significantly and, consequently, so has affordable housing.

As a result of increasing home costs and minimum Federal and Provincial funding, efforts have been made by the City of Vancouver to mitigate exponential increases in housing costs. Unfortunately, these attempts have had only limited success. For example, the well-intentioned implementation of the rate-of-change bylaw, which requires a one-to-one replacement of rental units for new developments in certain areas across the city, protects rental housing stock in a very limited capacity since it does not have the capability to prevent landlords from continually raising rents. This, in turn, has led to a number of superficial upgrades and tenant evictions across the city with those along Main Street being some of the most publicized.

The City’s approach to engaging affordability was outlined most recently in their Ecodensity Charter. The document clearly outlines the strategy they intend to use in order to lower the price of housing: more specifically, that an increase in density and provision of a greater mix of housing types will necessarily offset the costs of homes, while accommodating a wide range of households that will ensure a healthy diversity of people within Vancouver.

I’ve already argued in past articles that no direct measure, definitions, or targets are given to ensure affordable housing is built as densities increase—making the claim inherently questionable—and that affordability has a strong connection to construction and building type, among other aspects. Furthermore, I’ve also described in the last article how the provision of compact housing types—laneway homes, in particular—will not necessarily lead to lower house costs because of the spatial needs of the target demographic currently being forced out of the local market (families with children) and the direct costs associated with building larger homes despite smaller footprints.

With this in mind, there is no need to reiterate what has already been said. My purpose in this piece is to critique the very foundation of the argument: the status quo belief that densification necessarily leads to a drop in housing prices.

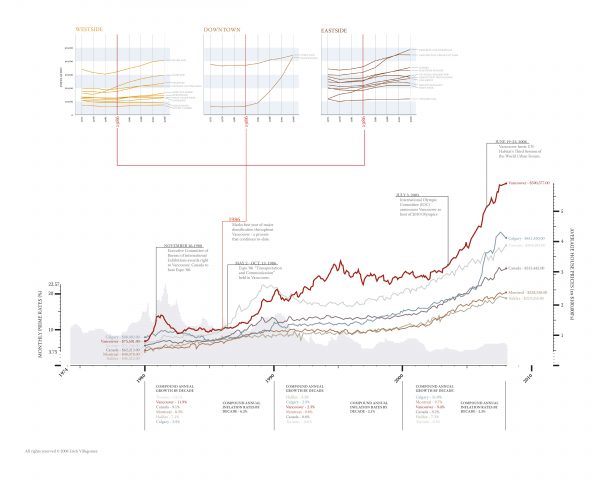

Although I definitely acknowledge that this is sometimes the case, by no means is it the rule. Locally, such a belief is both naïve and outright wrong. This is plainly clear in the accompanying graphic below showing the population growth and densification (upper graphs) and alongside the average costs of housing in all major Canadian cities.

Given that vast amounts of data represented, the information graphic requires explanation. The population growth charts at the top of the graphic – subdivided into Westside, East Vancouver, and Downtown for clarity purposes – depicts the census data of Vancouver’s growth from 1971 to 2006 (the most recent information available). Looking at the pattern, 1986 was a key year that began population explosion and construction of buildings to house them. This coincides with the zoning and regulatory framework created by the City that allowed higher density building to be constructed in specific locations throughout the city – Downtown and East Vancouver, in particular.

Below, the pivotal year of 1986 is shown amidst real estate and financial data showing the average price of homes across all the main cities in the country (from Jan. 1980 to Feb. 2008) along with monthly interest rates (in gray along the bottom) since 1974. Furthermore, the graphic is annotated with the years and events that many people believe had a particular impact on housing prices.

Taken together, these graphics show that housing prices have increased with densification and the growth of housing supply. This has occurred at a rate exponentially greater than other Canadian urban centers and is only partially explained by the Canadian economy—as represented by the interest rates.

An analysis of the information pattern even points to the possibility that densification can, in fact, go hand-in-hand with an increase in housing prices. Evidence of this is potentially given by the slight lag of price increase 1 to 2 years after 1986 when densification regulations were granted. Thus, 1987 and 1988 coincide with the completion of the first densification (high-rises, etc.) projects within the city. This point marks the beginning of Vancouver’s jagged rise in house pricing— continuing well beyond its Canadian counterparts.

This ultimately brings into question the fundamental assumptions behind the City of Vancouver’s strategy to combat the affordable housing issue: simplistically equating affordability with increasing housing supply.

Towards this end, responsibility must be taken by them to ensure, at the very least, that median wage earners within this region can afford median rental or ownership units within the city. This requires structuring policies and development regulations for this purpose and, in the words of Donald Elliot, author of A Better Way to Zone: Ten Principles to Create More Livable Cities, “acknowledging that the affordability of housing (not just the supply) is a zoning topic.”

But more on this in the final part of the series.

***

Other pieces in this series:

- The Costs of Unaffordability – Introduction

- The Costs of Unaffordability – Part 2: Affordability and Diversity

- The Costs of Unaffordability – Part 3: Affordability and Environment

- The Costs of Unaffordability – Part 4: Affordability in Vancouver

- The Costs of Unaffordability – Part 5: Epilogue

**

Erick Villagomez is one of the founding editors at Spacing Vancouver.