By Christopher Cheung and Jen St. Denis

It’s here at last — Vancouver’s long-awaited plan that will guide land-use decisions from density to design across all neighbourhoods until 2050.

Vancouver unveiled its city-wide plan today, with a focus on waking low-density residential neighbourhoods “from their slumber” and welcoming more floors and even corner stores to those quiet areas.

The draft confirms the direction the current council has set into motion: the end of neighbourhoods exclusively zoned for detached houses.

“Change is possible everywhere,” said Karis Hiebert, the planner who headed the process of consulting residents, businesses, organizations, professionals and government partners in the crafting of this draft.

The plan also talks about how the city can address widening inequities that have been brought into sharp relief by the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change-related crises like an extreme heatwave and smoky air caused by wildfires. City planners expect the city’s population to grow from 675,000 people today to around 920,000 by 2050.

The city-wide planning process started back in 2018, one of the first things the newly elected city council voted on.

The city was still reeling from a historic jump in property prices that left many Vancouverites feeling shut out of the city. Census data had shown that the city’s west side — where home values had soared into the millions or tens of millions — had lost population while most other neighbourhoods in the city had added new residents.

Why is the plan a big deal for Vancouver?

Unlike other B.C. municipalities, Vancouver does not have an official community plan. The province requires all local governments to come up with a plan for long-term growth every five years.

But Vancouver hasn’t had such a plan because it has its own charter, allowing the city to dodge certain requirements of the province’s Local Government Act.

This doesn’t mean that Vancouver is flying blind. Instead, a collection of neighbourhood-specific plans for growth have been developed over the years. One of the city’s former planning chiefs called it a “patchwork” and a “recipe for frustration” for residents and developers alike due to the uncertainty.

“There are so many policies, we don’t actually even know how many there are. Seventy-five? A hundred?” said planning director Theresa O’Donnell during the unveiling of the draft plan today.

O’Donnell explained the city’s numerous types of existing policies in detail. There are community plans for neighbourhoods like the West End, the Downtown Eastside and Grandview-Woodland. There are visions, which date as far back as the 1970s, for areas like Sunset and Riley Park. Some large sites have policy statements, such as Langara College and the Heather Lands. Then there are 14 official development plans, specific rezoning policies and city-wide policies like those for green building and incentivizing rental.

“So right now, people, businesses, developers have to wade through all of these different levels of plans to figure out which ones actually apply, which ones may be applied in the ’80s but they’re outdated,” said O’Donnell, “[and] which ones conflict or compete with other plans.”

This draft city-wide plan is the first attempt to “straighten” everything out.

It’s been four years since work on the plan began and Vancouver’s problems have only grown in size and complexity. Housing affordability is worse than ever, with rents and home prices again rising rapidly. Homelessness has likely grown (because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the city stopped doing an annual survey). Many local businesses and cultural spaces have closed, struggling with affordability and “demovictions” even before the pandemic.

In 2021, an extreme heatwave killed nearly 100 people in the city, mostly low-income seniors living in older apartment buildings. And the pandemic highlighted existing racial and socio-economic inequalities and led to a concerning rise in anti-Asian racism.

How does the plan intend to tackle all this? Here are some highlights.

Density for all

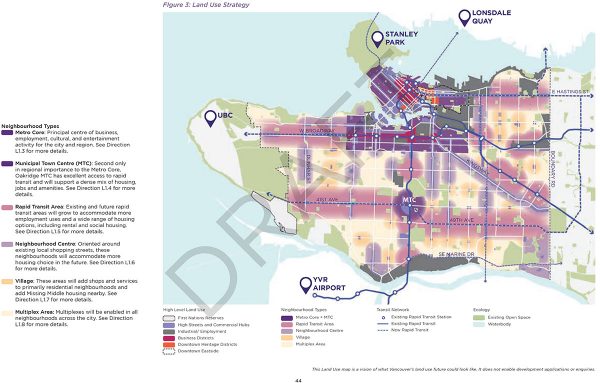

Vancouver has traditionally concentrated towers in just a few neighbourhoods: downtown, the West End and isolated spots of transit-oriented development like Marine Gateway. Low-rise apartment buildings are much more common near arterials and employment centres, scattered across Kitsilano, Fairview, Mount Pleasant and parts of East and South Vancouver.

But many neighbourhoods are still dominated by single-family homes (although city zoning rules now allow all owners to consider adding a basement suite, a laneway house or redeveloping into a duplex). Those houses have risen in value to the point that they’re no longer affordable to the average family.

In the draft plan, the “building blocks” of the city are largely the same — the difference is that everything will be intensified.

Single-family areas will become “multiplex areas.” The intersections and quiet commercial pockets off main roads will become “villages.” Major arterials and their surrounding areas will become “neighbourhood centres.” Rapid transit areas will see more development for housing and jobs, as will the metro core that now extends from the downtown to West 16th, including Broadway’s office corridor and the upcoming subway.

More floors and corner stores

In the city’s house-rich areas now designated multiplex areas, the draft plan says multiplexes can go up to three storeys, while apartment buildings can go up to six storeys if they satisfy a rental or social housing requirement.

The draft isn’t just calling for more homes in these zones. It’s welcoming corner stores, shops, community spaces and home-based businesses too.

Yes, this means that all the urbanists and residents charmed by the “four floors and corner stores” model of development could very well see them make a comeback to neighbourhoods where they have been prohibited.

If the multiplex idea sounds familiar, it is: Vancouver Mayor Kennedy Stewart announced a similar policy a few months ago called Making Home. It would allow homeowners to redevelop their homes into six units, which they could then sell as strata units. Stewart’s embrace of the policy comes as a civic election nears: B.C. residents will head to the polls this October, and housing is sure to be a top issue.

The divided city

Throughout the document, Vancouver’s west side neighbourhoods come up again and again as being home to the cleanest air, the lowest-density housing and plentiful amenities, such as parks, schools and community centres.

The Vancouver Plan notes that just 15 per cent of the housing in the city takes up 50 per cent of the land base, while one-third of neighbourhoods “do not have enough people living in them to support local businesses.”

Meanwhile, the plan says, housing for low-income people is concentrated in just a few areas of the city. The Vancouver Plan outlines a strategy of adding more “secure affordable housing options near transit, green spaces, schools and child care, and off busy streets.”

The plan also calls for adding more “missing middle” options like townhouses and low-rise apartment buildings in low-density neighbourhoods that don’t currently offer much in the way of affordable housing.

But the question is, will house-owners who love their houses actually go for anything denser? Data from the City of Vancouver shows far fewer laneway houses being built in west side neighbourhoods compared to East Vancouver. The mayor has suggested some incentives: aging house-owners could redevelop their property into a multiplex and downsize, profit off of the rest of the units or house their relatives on the same property.

Living with waterways

Vancouver has had a few water management projects in recent years, such as its Rain City Strategy. But the draft plan calls for a more holistic approach to managing water resources. Nature-based solutions should be prioritized, it says, and watersheds should be taken into account when considering infrastructure investments, land use changes and growth services.

And speaking of water…

City councillors Christine Boyle and Michael Wiebe had submitted a motion in 2020 calling the city to recognize public washrooms as a human right.

The draft plan’s wording reflects the motion: “Improving the safety, accessibility, availability and cleanliness of washrooms is a high priority for the public, particularly important for women and gender diverse people, people experiencing homelessness, sex workers, people who use drugs and other communities who rely on public washrooms for basic human needs.”

While libraries, community centres and most Vancouver parks have public washrooms, they’re only open during operating hours. And many high-traffic locations where you’d expect there to be a public washroom, from the plaza at the Vancouver Art Gallery to most transit stations, there isn’t one.

Loss of industrial land

The city’s industrial land base has been shrinking as it is converted to homes instead, with the vacancy rate of industrial properties at an all-time low of 0.6 per cent. Values and rents have soared, pushing tenants to leave Vancouver and relocate to the cheaper suburbs.

The draft plan calls for the study of the industrial areas around Marine Drive and Knight Street to see how they can be modernized, considering the demand for industrial sites and their access to roads, airport, transit, water and rail.

What’s missing?

Schools are one of Vancouver’s biggest pinch points in the uneven development of the city. In neighbourhoods where more housing has been added, like the West End, Downtown and Mount Pleasant, schools are full and many families are frustrated by waitlists.

In single-family home neighbourhoods — in past decades, seen as the most desirable areas for families — there is room in schools. And there is concern about continuing to build more housing in neighbourhoods where schools are already full.

City staff say they did consult with the Vancouver School Board throughout the development of the plan, and the ideas about adding density to low-population neighbourhoods would bring new life to under-used community centres and schools in those areas.

Also, the role of places of worship — churches, gurdwaras, temples and such — did not earn a mention in the plan, despite their presence in every neighbourhood in the city.

These places of worship still play a key role to both their congregants and the community at large, offering child care and senior programming, philanthropy, immigrant services and meeting spaces, all while combatting isolation and loneliness. Some have even gone on to redevelop their properties with affordable housing.

What’s next?

The plan is still in the draft stage and the public is invited to comment over the next three weeks. Staff will present the revised draft to councillors to vote on in June.

The results could throw a wrench into the plan if it fails to attract enough council support — especially with the possibility of different councillors after the fall election.

The plan is intended to be adopted as an official development plan in 2024, though some of its strategies are already underway.

Planning manager O’Donnell hopes this single document will help “detangle” the complicated web of policies that date back decades.

“It’s important that we send these messages about how we’re going to increase density,” she said. “We’re going to do these big concepts that we want the public to be aware of and let us know how they’re feeling.”

…

Christopher Cheung and Jen St. Denis are reporters at The Tyee, where this story originally appeared on April 5, 2022.

**

Christopher Cheung reports on urban issues for The Tyee. Follow him on Twitter at @bychrischeung. Jen St. Denis is The Tyee’s Downtown Eastside reporter. Find her on Twitter @JenStDen.