By 2050, an estimated one million new individuals are expected to make their home in the Metro Vancouver area. This projected influx of new residents is in line with the UN’s prediction that 68% of the world population will live in urban centres by 2050 which will inevitably result in more noise pollution—creating harmful urban environments that will need constant monitoring.

Noise can be defined as any undesirable sound that provokes discomfort. Beyond being an inconvenience, extended noise exposure can have lasting effects on our health including, but not limited to, elevated blood pressure, high heart rate, sleep disruption and hearing impairment. It also impacts urban wildlife, especially songbirds who are extremely sensitive to changes in their environment. Noise makes it more difficult for them to communicate with each other eventually leading to lower songbird populations which has an impact on the balance of urban ecosystems. As a result, ongoing noise monitoring is very important as decisions made by our policymakers and urban planners can affect the daily life and health of anyone living in a city.

Burnaby is British Columbia’s 3rd largest city. With a population expected to grow by 43% over the next 25 years, and as more residents now call South Burnaby home due to its many parks and easy access to public transportation, this inevitably implies more cars on the roads, more infrastructure being built to accommodate new residents resulting in a change the city’s soundscape.

In light of these transformations, a study was done to collect data to track how the city’s soundscape changes over time and document what drives those changes. The information was collected in South Burnaby, covering an area of approximately 11 km2 with a population of over 66,000 people and an average density exceeding 6,000 inhabitants per km2.

To collect our data, we repurposed smartphones running on Android 6 and 7 using a customized TensorFlow Lite Model, a machine-learning model specifically designed to be used on devices, such as smartphones, capable of recognizing a wide range of sounds. This took advantage of the smartphones’ computing power to conduct unmanned surveys lasting up to 12 hours while the devices run on battery alone. Collecting the information was intended to give people some actionable insight into building urban spaces that prioritize both human well-being and environmental sustainability.

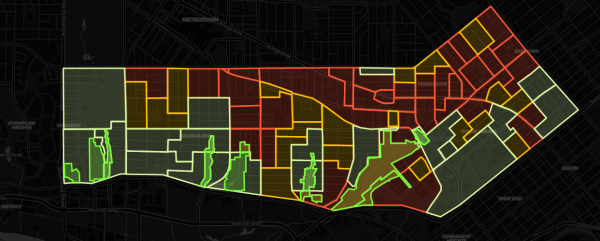

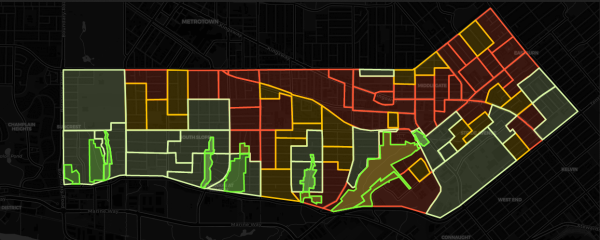

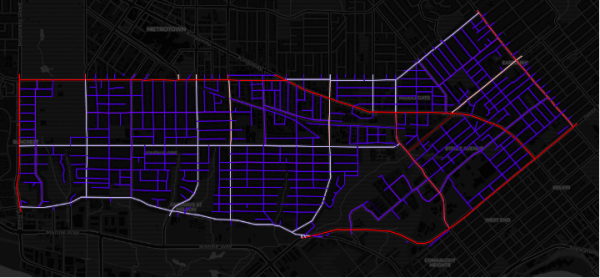

The interactive map below is a visual and audio representation of the data collected. It allows residents to compare acoustic data within certain neighbourhoods of South Burnaby. By hovering your mouse over it one can hear actual sounds recorded during our surveys. Those recordings include for the most part vehicles (cars, buses, trucks), rail transit, songbirds, and ambient noise.

The map provides data down to the local level to allow policymakers and urban planners to make informed decisions. The scale of colours indicates the nature and intensity of the noises. Areas in dark green represent areas with negligible urban noises and mostly songbird sounds, while areas in red correspond to areas where traffic and rail transit are the most common sources of noise. The boundaries used on the map represent what Statistics Canada refers to as Dissemination Areas (DA) and they are made up of adjacent blocks including between 400 to 700 residents.

The surveyed area is not representative of the entire City of Burnaby. So, the following insights and takeaways are specific to our region of interest and should not be extrapolated to the rest of the city. That said, much can be learned from the work.

Zoning and Parks

Roughly 88.9% of the area we cover is zoned for residential use, 4.8% is dedicated to parks and open spaces and approximately 4.7% for commercial purposes while 1.5% is zoned for institutional use. Quieter areas are located in the southern part and tend to be closer to conservation areas and ravines (dark green) and to neighbourhoods located close to locations zoned mostly for Single Family Homes (light green). The noisiest neighbourhoods (orange and red on the map) were located near major roads and rail transit: the 2 main sources of noise in the area we surveyed.

Roads

Roads are the main source of noise. The map below shows the different categories of roads that span across the area. Intermittent noise level recordings confirm that the average decibel level varies based on the classification of each road. Residential roads (in blue) are quieter than major roads (in red and white) where most of the traffic happens due to the use of cars, buses, or trucks.

Inequalities

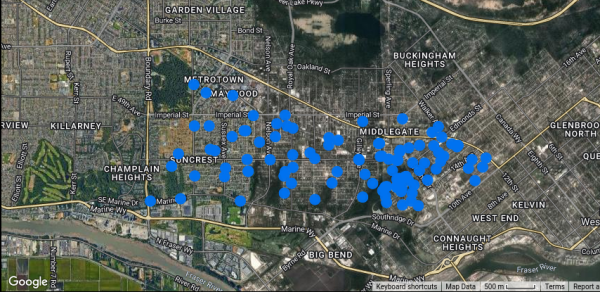

Denis Agar from Movement and Jens von Bergmann from MountainMath have created the map below to show the distribution of renters across Metro Vancouver. When zooming in on South Burnaby, one quickly notices the positive correlation between noise and renter density. In other words, the quietest neighbourhoods have the lowest tenant density while the majority of the noisiest neighbourhoods have a high tenant density.

While considering that correlation does not imply causation, we can state that people who rent are more likely to be exposed to urban noises and suffer from long-term health implications. On the other hand, homeowners are more likely to live in areas with minimum exposure to noise and as a result, are less likely to suffer from it. These conclusions align with the World Health Organization which states that “the less affluent who cannot afford to live in quiet residential areas or have adequately insulated homes, are likely to suffer disproportionately.”

Songbirds

Songbirds play a central role in urban ecosystems. They contribute to pest control and their active participation in seed dispersal is equally important to ensure floral diversity in our cities. In 2005, Stephanie J. Melles, then at the Department of Zoology of the University of Toronto, conducted a study in Vancouver and parts of Burnaby that concluded that “wealthier neighborhoods have more native species of birds and that these native species increase in abundance as the socioeconomic status of the neighborhood improves.”

The City of Burnaby’s first Urban Forest Management Strategy whose goal consists in “creating a diverse, resilient and healthy urban forest by protecting, preserving, restoring and expanding tree cover throughout Burnaby.” does not specifically address the year-round support of native songbirds in parks and neighbourhoods. If successful, however, this program would provide healthy and diverse habitats for the songbird population. The data collected allows us to model the distribution of the songbird population and eventually track how neighbourhoods compare over time in maintaining healthy ecosystems.

The Next Phase

Our goal is to set up autonomous noise stations in strategic locations to collect live data and make it available to all. To achieve that goal, we aim to create partnerships with community members and for-profit organizations to help monitor noise levels in different parts of the city. Noise is a powerful indicator. It allows us to measure the well-being of our neighbourhoods and cities while tracking the state of urban wildlife population and pointing out social inequalities. We believe the data we gathered is valuable as it provides actionable data for community members, stakeholders, and policymakers to build neighbourhoods as envisioned in the 2050 Burnaby plan.

***

Click here to go to the the interactive map.

**

Thierry Haddad is the co-founder of The Citrus Index, an organization that specialises in collecting and analysing data related to noise, solid waste and urban wildlife using data science, computer vision, audio classification and machine learning.