The more things change the more they stay the same. – Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr, 1849

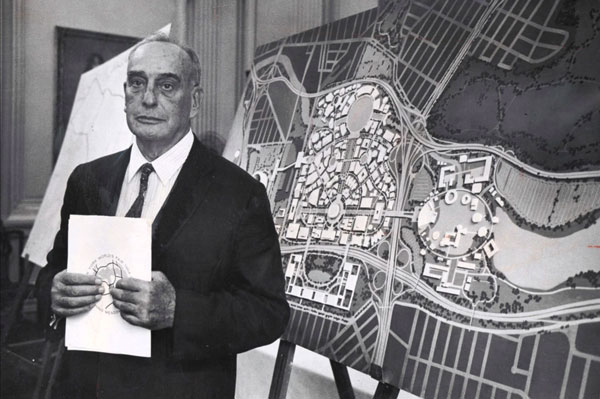

Robert Moses is a controversial figure in urban planning history, whose influential reach exploded far beyond the native soils of his New York City boundaries. Known as NYC’s “Master Builder”—and more recently the focus of 99% Invisible’s The Power Broker series—his projects span the 1920s to the 1970s and radically reshaped the urban fabric at all levels. From the construction of highways and bridges to parks and public housing, Moses was not only known for his grand vision, but also his ability to execute large-scale projects with remarkable speed and efficiency.

His secret formula? Top-down, autocratic methods that disregarded public opinion complemented by his ability to convince those in power that he was simply an agent of an unstoppable global force called modernity. Consequently, his projects displaced thousands of low-income and minority communities—easy targets for locating his works. While some argue that his projects brought “modernity” and “progress”, they highlight the social costs and inequities inherent in large-scale urban planning.

One of Moses’ most memorable statements: When you operate in an overbuilt metropolis, you have to hack your way with a meat ax. I’m just going to keep right on building. You do the best you can to stop it. Implication? Animal corpses are “people in the way.” It’s enough to make one wince.

Marshall Berman—who would later write the renowned and insightful book, All That Is Solid Melts Into Air: The Experience of Modernity—who had grown up in the Bronx, and recalls standing above Moses’ Cross-Bronx Expressway construction site and weeping openly, emotionally shattered, for his beloved neighbourhood. He was not alone.

Vancouver was not spared his influence. Local apostles proposed a multi-lane highway cutting across East Vancouver with surgical precision through the ethnic enclaves of Chinatown, Strathcona and Gastown on its way across the downtown waterfront. Hogan’s Alley ” the first and last neighbourhood in Vancouver with a substantial concentrated black population” was one of its several casualties. All this, in the name of “progress”.

The fate of the proposed highway, the government that supported it, and that of Moses mirror each other. Moses’ 40 years of creative destruction fostered the growth of thousands of “smaller” enemies, many as resourceful as himself. His proposal for the Lower Manhattan Expressway and extension of Fifth Avenue through Washington Square Park that threatened to displace thousands of residents brought to light one particularly important unassuming figure: a prominent urban activist and writer by the name of Jane Jacobs who championed a different version of ‘modernity’: one built on the recognizing the strong patterns of the everyday lives of urban communities.

The yin to Moses’ yang, she proposed an approach to urban planning that emphasized preserving vibrant neighbourhoods and advocated for the involvement of residents in shaping their environments. An approach that recognized and embraced the complexity of the urban and did away with the oversimplified models of the urban planners and politicians of the time.

Jacobs paved the way (pun intended) to preserve many important historic neighbourhoods by mobilizing community support through grassroots activism, public demonstrations, and media campaigns. Her influential book, “The Death and Life of Great American Cities,” insightfully criticized large-scale urban renewal projects for destroying the important social fabric of communities and offered a swift and deadly strike: leaving Moses’ top-down planning methods impotent and marking a significant shift in urban planning philosophy. One that made an impact locally in the creation of processes that built community trust. This showed the ignorance of simplistic views of cities and the power of community activism. As a result, Jacobs and her supporters profoundly influenced the development of cities worldwide.

Jane Jacobs was no stranger to Vancouver: joining in the rallying cry that brought Vancouver’s freeway dreams—and those politicians who upheld Moses’ vision of progress—to an end. This forever changed the course of the city—resoundingly in the best possible way. The intelligence of Vancouver’s urban communities was clear.

Over five decades later, Vancouver and we, its urban communities, find ourselves where we once were, against the next generation of Moses apostles. Similar top-down, autocratic methods underpin many current initiatives, from the Province’s heavy-handed approach to Transit-Oriented Areas to Vancouver City Council’s handling of the Broadway Plan, let alone their attempts to end community input altogether. They are “hacking their way with the meat ax” through mature, vibrant neighbourhoods and established community-led processes with one-size-fits-all, market-biased solutions at breakneck speeds to make up for decades of underfunding and “pro-market” neglect.

Consider this: the Broadway Plan and failed Freeway proposal are roughly the same length. The Broadway Plan has 500 blocks directly slated for transformation—a.k.a. destruction—most of which are existing mature communities and some of which are already among the densest in the city. Statistically, the Broadway Plan will directly affect and displace more people than the Freeway. Add the regional transformations mandated by the Province and the numbers are staggeringly higher. All this with minimal, if any, meaningful community engagement and a blatant disregard for public opinion.

Sound familiar?

Say goodbye to mom-and-pop stores that enrich our daily experiences. So long to the neighbourhood and community plans that so many people fought tooth-and-nail to create and uphold. Farewell to the mature rental buildings and all those who live in them. Fear not, they will promptly ship you elsewhere. This crisis demands your sacrifice. The New Vancouverites will thank you from their FOB-secured buildings as they swagger their way to their private rooftop gardens.

Socially just planning simply has no place in this crisis-ridden time—“esteemed economists” say so and have modeled this out of their perfect, utopian world. A world where people are abstract numbers. Their homes, communities, and support systems….blank spaces within dashed circles of “Prescribed Distances”. Those unfortunate enough to be in the void are simply externalities. Why bother taking them into account when they are temporary squatters, right?

Like Moses, our government is seduced by the (over)simplistic assumption of the blank slate. The clean sheet for urban destruction. Buoyed by the arrogant, Modernist confidence that the new will somehow be better than the old. That adding abstract, anonymous people alone will save the city. Moses approves.

Frances Perkins—who worked closely with Moses and was America’s first woman appointed to a presidential cabinet as Secretary of Labor under Franklin D. Roosevelt—astutely described one of Moses’ more disturbing qualities as a person who “…loves the public, but not as people.” This incredible cognitive dissonance holds for both the Province and the City of Vancouver.

Now, Moses supporters argue that he made important contributions to public infrastructure, housing, and public spaces—like parks—that would benefit many over the years. A legitimate argument: although a true, non-biased cost-benefit analysis has never been done…and never will. But this is certainly more than the Province and Vancouver Council can argue about their work: one that offers minimal public good while maximizing private benefits—hiding behind highly debatable arguments and false accusations of “NIMBY-ism” to support their dictatorial behaviour.

Another Moses quote: “There are people who like things as they are. I can’t hold out any hope for them. They have to keep moving further away….Let them go to the Rockies.”

Sound familiar?

A challenge: if they are so confident in their decisions—their bullet-proof arguments—why not be completely transparent and lay it all out for the Public to decide? Models, formulas, and all. Majority wins. The Community is smart enough to understand them. We promise. Let’s call it a “market analysis” if it makes you feel more comfortable. The Community dares you.

Love him or hate him, at least Moses was transparent enough to not pretend to listen to anybody. He was honest enough to call a meat ax what it was. And let’s be clear, Moses’ fabricated “crisis” was as much about “modernity” as ours is about “affordability”. In both cases, it is a crisis of planning. Nothing more, nothing less.

Insofar as our local governments are learning from the Book of Moses, it is important to remember this small lesson: his transformative power—built on an oversimplistic arrogance similar to what we are seeing today—was ultimately bested by the humble authority of urban communities. A recurring historical pattern that has tumbled much more than just freeways.

***

Related Spacing Vancouver pieces:

- Trifecta of Control

- Entitled to Flip

- When Care Becomes Control

- The Slow Emergency

- The Broadway Plan Blues

- Learning from Moses

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.