The city, we’re often told, is a model—something to be learned from, exported, improved. But what happens when models conflict? What if the city itself resists being modelled?

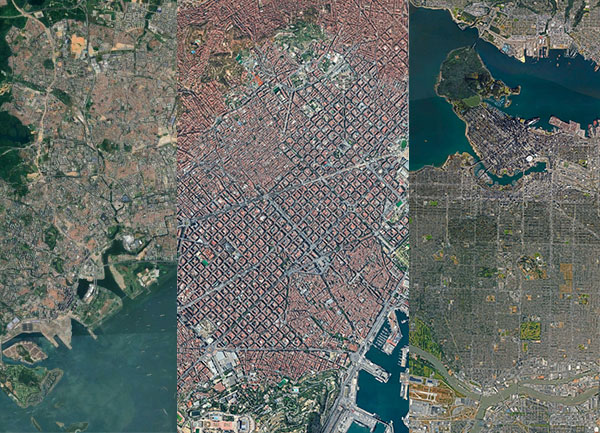

Throughout the Chronicles series so far, we’ve walked the ordered streets of Singapore’s HDB towns, cycled through Barcelona’s evolving housing policies, and revisited Vancouver’s once-promising but increasingly faltering approach to city-making. In this final reflection, we bring these trajectories into the conversation—not to crown one as superior, but to ask what each reveals about the choices we make when shaping urban life.

Singapore: The State as Planner, Developer, and Custodian

Singapore offers perhaps the world’s most comprehensive state-led urban experiment. In a land-scarce city-state, density is not a choice but a necessity. Yet, Singapore has turned that constraint into a strength. Through integrated planning agencies and a powerful Housing & Development Board (HDB), it has delivered high-quality, affordable public housing to over 80% of its population. Greenery is ubiquitous. Infrastructure is immaculate. The city feels orchestrated—because it is.

This technocratic approach has delivered undeniable outcomes: social stability, housing equity, and efficient land use. But it has also raised questions about spontaneity, inclusiveness, and bottom-up engagement. Public space in Singapore is verdant, yet curated; its housing is affordable, yet surveilled; its success, while impressive, can feel insular and self-referential.

Importantly, Singapore’s planning culture is built on clarity and precision. Objectives are explicitly articulated, targets meticulously tracked, and policies implemented with a data-driven, evidence-based mindset. This transparency provides coherence across many agencies and instills public confidence in long-term planning outcomes.

A prime example is the “Healthy City” initiative, where evidence from the Healthy City Design Playbook is used to embed walkability, access to services, and active lifestyles into urban planning at the neighbourhood scale. Indicators such as access to parks, path connectivity, and proximity to fresh food sources are not just aspirational—they are measured, tracked, and continuously refined.

Singapore also keeps market forces at arm’s length in housing provision. The HDB operates as a public developer with extensive land control, ensuring that housing supply is not left to speculative cycles. Instead, a mix of grants, eligibility schemes, and complex state-financed models is used to deliver affordability and stability, with homeownership linked to broader social policy goals.

While Singapore’s governance remains largely top-down, there is a discernible shift towards addressing community concerns more proactively. Initiatives such as neighbourhood-level engagement in planning upgrades or feedback on liveability metrics show a growing recognition of the value of local input—albeit within a carefully managed framework.

Barcelona: Tactical Urbanism and the Reclamation of Space

Barcelona, by contrast, is messy—in the best way. Its planning model, especially under the Ada Colau administration, has been defined by tactical urbanism, iterative pilots, and citizen-led transformation. The Superilla initiative didn’t necessarily emerge from a five-year plan, but from a desire to reclaim streets for people and push back against car dominance. It evolved, block by block, from Poblenou to Sant Antoni to the sweeping green axes of the Eixample.

What Barcelona offers is not efficiency, but democratic spatial politics. It reminds us that streets are not just conduits, but places. And that public space can be both ecological infrastructure and cultural commons. Yet, its model is not without limits. Political turnover, economic pressures, and implementation challenges have hindered the scaling of many ideas. The vibrancy of the model is also its fragility.

Yet, like Singapore, underpinning Barcelona’s civic experimentalism is a deep commitment to evidence-based planning and a drive for transparency and clarity. The city has made deliberate efforts to define concepts—such as “affordable housing“—with accessible, comprehensible metrics. Also, the 30% measure mandates that any new private housing development must allocate 30% of its floor area for protected housing if it meets certain thresholds.

This simple yet impactful policy emerged from robust policy studies and public consultation, reflecting a culture of clearly defined goals backed by data and iterative evaluation. Policies are informed by neighbourhood-level data, environmental indicators, and community feedback, which collectively shape a transparent, iterative planning process.

Also like Singapore, Barcelona actively resists ceding housing provision to the market. The city leverages a mix of municipal land, public-private partnerships, and cooperative housing models to expand its social housing stock. Its approach combines political will with creative financing, keeping affordability within the public realm despite broader European austerity trends.

At its core, Barcelona’s urban transformation is rooted in community. The city views residents not just as stakeholders, but as co-creators of space. Planning here is imbued with the spirit of co-production—policies are debated in open forums, interventions trialled and revised, and neighbourhood identities honoured in the process.

Vancouver: The Mirage of Market-Led Livability

Then there is Vancouver—a city that once led North America in progressive urbanism. Today, its planning ethos feels adrift. While it boasts some of the continent’s best urban design in places like Olympic Village or Arbutus Walk, these are islands in a sea of unaffordable housing and developer-driven planning. The language of livability remains, but its foundation has eroded.

Unlike Singapore or Barcelona, Vancouver has embraced the market as planner-in-chief. Its reliance on density bonuses, developer levies, and upzoning has fuelled speculation rather than inclusion. Community plans give way to economic imperatives. Affordable housing goals are trumped by political expedience. Runaway housing prices have resulted. The city’s promise—once rooted in community consultation and human-scale design—has dimmed.

Worryingly, Vancouver is moving away from the very community input that once made it a model of participatory planning. Recent shifts have seen neighbourhood advisory processes weakened, public hearings curtailed, and rezoning decisions fast-tracked with minimal resident engagement. The result is a planning process that feels increasingly opaque—one where the voices of investors and developers speak louder than those of long-time residents.

Vancouver’s lack of definitional clarity and data transparency has further compounded its challenges. There is no unified or consistently applied framework for tracking housing affordability, development outcomes, or spatial equity. Key decisions—especially around rezonings and housing targets—are often made with little reference to robust datasets or shared indicators.

This absence of an evidence-based foundation undermines both public trust and policy coherence, leaving planning vulnerable to shifting political narratives and economic pressures. Terms like “affordable housing” are fluid and politically expedient, disconnected from real cost-of-living metrics.

Without consistent benchmarks or an evidence-based framework, policy debates become muddled, and outcomes suffer.

Three Models, Shared Tensions

Despite their divergences, all three cities confront similar challenges: climate adaptation, social equity, urban mobility. Each city wrestles with how to densify while maintaining liveability; how to create inclusive public spaces; how to govern amidst complexity.

What sets them apart is not the problems, but the paradigms:

- Singapore governs from above, designing for cohesion.

- Barcelona builds from below, designing for reclamation.

- Vancouver defers to the market, designing through omission.

Each model holds lessons. Singapore teaches the power of foresight and state capacity. Barcelona shows how spatial democracy can thrive with courage and care. Vancouver warns of what happens when vision is replaced with profit.

Beyond Models

But perhaps the most important lesson is this: cities are not models. They are not blueprints to be photocopied, nor abstractions to be admired from afar. They are living systems—shaped by context, culture, and time.

If there is a model worth emulating, it is not any single city, but a way of working: with humility, evidence, iteration, and deep respect for the people who inhabit urban space. The true question isn’t which city to copy, but what kind of city we want to become.

The answer, as ever, begins beneath our feet.

***

All pieces in The Singapore Chronicles:

- Part 1 – Introduction: The Paradoxical City

- Part 2 – Singapore’s Urban History in Four Acts

- Part 3 – The Politics of Preservation

- Part 4 – Housing the Nation

- Part 5 – Memory in the Margins

- Part 6 – Designing for Urban Health

- Part 7 – Conclusion

- Part 8 – Divergent Models: Singapore, Barcelona, Vancouver

**

All pieces in The Barcelona Chronicles:

- Part 1: Introduction

- Part 2 – Cerdà and Colau: Two Key Figures

- Part 3 – The Barcelona Housing Policy 2015-2023 Overview

- Part 4 – Defining Affordable & Social Housing

- Part 5 – Supplying Affordable Housing

- Part 6 – The 30% Measure and Others

- Part 7 – Vancouver v. Barcelona – Foundations

- Part 8 – Barcelona v. Vancouver – Strategies

- Part 9 – The Eixample and the Superilla

- Part 10 – The Superilla Pilot

- Part 11 – The Superilla…Evolved

- Part 12 – Vancouver v. Barcelona – Urban Design

- Part 13 – Reflections on Two Cities

*

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.

2 comments

For your next visit—if you’re done spewing carbon into the air to score some cheap political points—you might want to visit a city that blows all of these out of the water in terms of affordability. Edmonton boasts some of the highest incomes in Canada while having some of the cheapest rents and homeownership costs. There’s even a train to take you there. And perhaps you might even learn something about your own country: what works there and what doesn’t, for a change.

Hi Again,

You’ll be glad to know that representatives from Edmonton were actually part of the trip—and they had valuable insights to share, as well as a genuine interest in learning from Singapore’s approach.

You’re absolutely right that cities like Edmonton offer a meaningful counterpoint. There’s much to learn from the diversity of urban forms within Canada—just as there is from international contexts like Singapore. The purpose of these comparative explorations isn’t to declare winners, but to better understand the trade-offs that different urban systems make.

There are no one-size-fits-all solutions. Edmonton’s model has its own strengths and challenges, as do others across the country. The spirit of the trip was to understand how cities respond to common pressures—housing affordability, climate adaptation, demographic change—in locally specific ways.

Urban planning is rarely about absolutes. It’s about navigating difficult trade-offs between land use and environmental impact, affordability and equity, policy ambition and lived reality. That’s what makes it both so complex and so important.