What happens when four different reports give four different answers to the same housing question?

Every few months, a new report is released with a headline number meant to define the scale of CanadaŌĆÖs housing crisis. These numbers are treated like hard facts: how many homes need to be built, how fast, and by when. But dig beneath the surface and you find something messier: a battle of assumptions, values, and visions of the future. Like doctors offering different prescriptions for the same patient, each is confident and grounded in evidence, but all are diagnosing the problem differently.

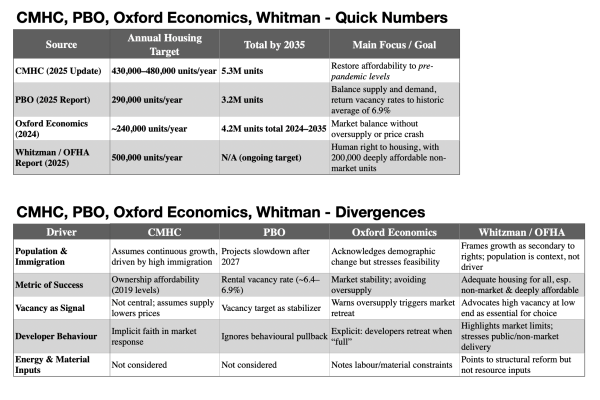

Four recent reports illustrate this divide: Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO), Oxford Economics, and a rights-based framework developed by Carolyn Whitzman and the Office of the Federal Housing Advocate. Their conclusions differ so dramatically that itŌĆÖs fair to ask whether theyŌĆÖre even talking about the same problem.

Let’s look critically at each.

The CMHC report assumes that the path to solving the crisis lies in dramatically increasing the total number of homes built each year, nearly doubling the current construction pace. Their goal is to bring home prices back to pre-pandemic levels, a benchmark that already represented serious affordability challenges for many households. CMHCŌĆÖs model envisions continuous population growth driven by immigration and interprovincial migration, and it assumes that the market, if supplied with enough units, will eventually bring affordability to middle-income households. It does not focus specifically on the needs of low-income renters, but rather on the overall health of the national housing market.

The PBO takes a more restrained view. Their report projects a sharp slowdown in immigration after 2027 as federal policy changes take hold, resulting in lower household formation rates. Their focus is not on restoring a certain price-to-income ratio but on increasing the vacancy rate to a historically healthy level of 6.9 percent. By concentrating on the balance between supply and demand rather than price levels, the PBO suggests that fewer units are needed overall than CMHC projects.

While this focus on vacancy rates and ŌĆśsuppressed householdsŌĆÖ broadens the conversation beyond ownership, it also narrows the lens in other ways. The PBO assumes that doubling up is the main fallback for unmet demand, overlooking harsher realities like homelessness, eviction, or leaving expensive but opportunity-rich cities.

Even its use of a 6.4ŌĆō6.9 percent ŌĆśhistoricŌĆÖ vacancy benchmark departs from the 3 percent figure most municipalities treat as healthy, reminding us that even neutral-sounding targets are choices about which signals to privilege. In this sense, the PBO is like a doctor treating the fever but not the underlying infection.

Oxford Economics adds yet another perspective. Their analysis emphasizes practical constraints, warning that the near tripling of construction rates implied by CMHCŌĆÖs targets is simply not feasible given current workforce and material limitations. They also raise the spectre of oversupply, arguing that building too much too quickly could lead to one in five homes sitting vacant by the mid-2030s. Such a surge, they caution, might not only destabilize housing markets but also crowd out investments in other sectors of the economy, with long-term consequences for productivity and growth.

Their caution also speaks to the behaviour of developers themselves. Markets rarely sustain oversupply, because once vacancies begin to rise, builders quickly pull back. Like patients on Ozempic, developers feel ŌĆśfullŌĆÖ very quickly: even a small bump in vacancies can be enough to trigger retreat. The marketŌĆÖs appetite, in other words, is more like a picky eater than a bottomless pit. That fragility makes the kind of sustained high building rates envisioned by CMHC all the more implausible.

WhitzmanŌĆÖs report, developed for the Office of the Federal Housing Advocate, reframes the debate entirely. Rather than focusing on aggregate numbers or vacancy rates, it grounds its recommendations in the legal and moral right to adequate housing. Whitzman argues that solving CanadaŌĆÖs housing crisis requires building 500,000 homes a year, with 200,000 of those being non-market and deeply affordable for low-income households. This framework explicitly counts populations often left out of other models, including those experiencing homelessness, hidden homelessness, and forced displacement from job- and service-rich communities.

This stands in sharp contrast to the PBOŌĆÖs narrower approach, which treats suppressed households as the main measure of unmet need. By explicitly counting homelessness, hidden homelessness, and displacement, Whitzman expands the frame to reveal groups who never even register in the other models. It calls for a profound transformation in how housing is financed, governed, and distributed.

Each report also measures success differently. For CMHC, the benchmark is restoring ownership affordability to 2019 levels, even though those levels were already unaffordable for many. The PBO, by contrast, defines success in terms of rental vacancy rates, treating a return to a 6ŌĆō7% rate as the marker of balance. Oxford focuses on market feasibility and stability, while Whitzman reframes success entirely as meeting the human right to housing.

The gulf between these reports stems from their underlying assumptions. CMHC assumes continuous population growth and market self-correction, while the PBO anticipates a slowing of immigration and focuses on vacancy as a stabilizing force. Oxford Economics challenges both by pointing to hard limits on construction capacity and the risks of overshooting demand. Whitzman introduces a different metric entirely: human need, measured not by market indicators but by whether everyone has a safe, affordable place to live.

Vacancy is a good example of how these metrics carry different political meanings. In Sweden, the success of the Million Programme in raising vacancy rates helped bring down a government in the 1970s. In Medicine Hat, by contrast, an 11 percent vacancy rate underpinned a short-lived ŌĆśzero homelessnessŌĆÖ miracle. Far from being a neutral indicator, vacancy can be a political flashpointŌĆösignalling stability in one context and crisis in another. ItŌĆÖs a bit like reading a weather forecast: a sunny day is good news for picnickers but bad news for farmers praying for rain.

These are not just technical disagreements but fundamentally different visions of what success looks like.

For Vancouver, these debates are far from abstract. CMHCŌĆÖs high-end projections would mean a construction boom of unprecedented scale, further straining already limited labour and materials. The PBOŌĆÖs more cautious forecast suggests current build rates could be enough if immigration slows. Oxford Economics warns that pushing too hard could backfire, flooding the market with vacant luxury units and worsening volatility.

Meanwhile, WhitzmanŌĆÖs framework reminds us that even a city full of cranes can fail its most vulnerable residents. VancouverŌĆÖs low-income renters face near-zero availability, a reality completely invisible in aggregate national vacancy numbers.

ItŌĆÖs important to recognize that housing projections are often treated as objective truths. The stakes are enormous: municipal and provincial governments, lenders, and especially the development community watch these reports closely, using their numbers to justify large-scale investments and rezoning decisions.

Developers, in particular, watch vacancies like hawks. Any sign of ŌĆśtoo muchŌĆÖ supply, and they scale back, leaving cities stuck in cycles of scarcity and boom. Projections may say more supply is needed, but the marketŌĆÖs self-correcting instincts often prevent overshooting for long.

Ultimately, these numbers shape multi-billion-dollar decisions, and if the projected need is high, it can fuel speculative behaviour and drastically alter the skyline of cities like Vancouver.

Vaclav Smil reminds us that urbanization and economic expansion rely on massive flows of energy and materials that are rarely accounted for, and how population trajectories can shift suddenly due to social, political, or environmental changes. These omissions make long-term forecasting even more fragile, particularly when applied to complex urban systems like Vancouver, where these underlying forces are constantly in flux. In SmilŌĆÖs terms, building projections without energy and materials is a bit like planning a road trip without checking the fuel gauge.

What can we take away from this discussion?

Seen together, these four reports highlight how housing projections are less about certainty and more about competing worldviews. They are really political choices wrapped in statistical models. The question isnŌĆÖt just how many homes Vancouver needsŌĆöitŌĆÖs which people we are building for, and what kind of city we want to create.

This leaves us with a paradox: for some, like UN housing advocate Leilani Farha, any vacant unit is a failure; for others, true affordability depends on a surplus of empty homes, especially at the lower end of the market. The same vacancy rate can be interpreted as either a success or a disaster, depending on the worldview appliedŌĆöa reminder that the politics of housing are always embedded in the numbers.

As Vancouver wrestles with its future, perhaps the most provocative conclusion is this: whatever numbers experts put forth, the real question becomesŌĆöand always has beenŌĆöwhich vision of the city we want to embrace.

***

Below are summary tables for reference:

**

Other related articles:

- The Slow Emergency

- The Slow Emergency, Part II: The Emergency Escalates

- Trifecta of Control: Stealth. Speed. Compexity

- Entitled to Flip

- When Local Planning Becomes Provincial Command

- The Coriolis Effect, Part I: Planning by Spreadsheet

- The Coriolis Effect, Part II: Beyond the Spreadsheet

- The Coriolis Effect, Part III: Reclaiming the PlannerŌĆÖs Toolkit

- The Coriolis Effect, Part IV: When Viability Becomes Destiny

- When Care Becomes Control

- The Broadway Plan Blues

- Learning from Moses

*

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBCŌĆÖs School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.