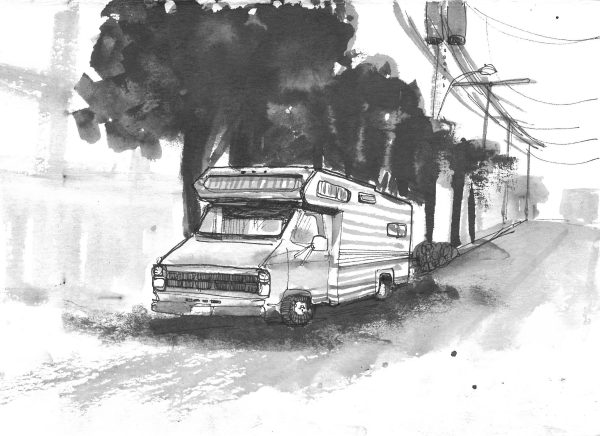

Yvonne was in her early 40s, with short brown hair and a solid build. She was taller than my 5’ 5” frame, but when I met her she was seated on the steps of her six-passenger bus, concentrating on something in her lap. In the boulevard in front of her were a few items that she was selling as part of a tiny yard sale – some cups, a rope, articles of clothing, and a cat dish. She was parked across from a turn-of-the-century house that was awaiting renovation building permits, with no residents who would complain about her and her bus.

As I browsed through her items, Yvonne told me she was raising money to buy more faux crystals for her art project. In her lap, she had an army helmet which she was decorating with costume jewelry – a puzzle of delicateness adorning a piece of unyielding military gear. The contrast of materials was striking. Next to Yvonne was her cat, a black and white mouser named Simon. Yvonne told me that Simon “didn’t so much like the bus,” but wouldn’t leave her side. He was her constant companion as she travelled from one parking spot to the next. I couldn’t see into her bus, but from what I could tell through the open doorway, there was a living area behind the driver’s seat. Curtains covered the windows and secured her privacy.

Yvonne was easy with her words, and her voice had a slight French accent.

“I’m Métis,” she told me. “From Saskatchewan. But it is too cold there.”

I asked her about the helmet, and she told me she was creating an art piece to be sold at an online auction.

“Last year, the helmet I made sold for $3000. The money is for charity for ex-military, for their medical expenses.”

She took out her phone and showed me a photo of last year’s helmet. It was strikingly beautiful. The military green was covered with wisps and turns of red paint in an Indigenous design, representing what looked like a mythical creature. Last year’s helmet felt more forceful than this year’s, and less tactile as well. I wondered if the gentle, feminine feeling of this year’s helmet was intentional and whether it would garner the same high price.

“I was in the military. That’s why I make these,” she tells me as she puts her phone away.

There was nothing in her presence that suggested anger or frustration for having served her country, for being a survivor of centuries of genocide, or for having been a woman in a non-traditional career, only to be left on the sidelines in her bus. My anger and frustration from hearing her story was my own white, middle-class privilege storming around in my head. I don’t think Yvonne wanted or needed my outrage. More likely, she just wanted someone to talk with about her art and to share information about the veterans’ foundation she was supporting.

I didn’t end up buying anything, but I gave Yvonne $20 for more crystals. The bus was there for another day or two, and then she moved on. I never saw the final version of her art or learned from her whether she had been successful in surpassing last year’s auction price. After speaking with her, I contacted the charity and learned that 2,500 military personnel are ‘medically-released’ each year. Of these, 38% fall between the cracks after their service. I would guess that Yvonne was part of the 38%.

Yvonne was one of the first people I met who I would later come to call 21st-century road allowance people.

In 1995, writer, filmmaker, and academic Maria Campbell published Stories of the Road Allowance People, a translation of oral histories of the Métis from Canada’s Prairies. The history of the road allowance people began after the failed Métis rebellion of 1885. When they lost the fight for their right to land title, many Métis dispersed from the Red River Valley to undeveloped lands across the prairies, including parkland, forested regions, as well as the nine metres (30 feet) of Crown land on either side of future highways. These nine metres of homestead is where the displaced Métis got their “road allowance” name.

The Métis lived on road allowances from 1885 to approximately 1960. It was an extremely hard life that lacked basic amenities and denied them their children’s right to public school: houses were usually uninsulated, roofed with tarpaper, and built from discarded lumber or logs and various “recycled” materials. These small one- or two-room dwellings housed entire families. Road allowance Métis also lacked educational opportunities because children were not allowed to go to school if their parents didn’t pay property taxes. As a result, three generations of Métis were unable to receive a basic education.

By the 1960s, the highways were built, and once again, the landless Métis had to find other places to call home.

The story of the first road allowance people is part of Canada’s long history of public land being used for makeshift housing when nothing else is available. Today, with a scarcity of affordable housing, more and more people, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, are becoming 21st-century road allowance people, living on the sides of roads in their vehicles.

There is no hard data about how many people are using their vehicles for shelter. While Statistics Canada has numbers on people living in a “movable dwelling,” this refers to a mobile home in a trailer park. People living in transitional housing or shelters may be included in the census count, but those living in vehicles with no permanent address are not. Among those without stable housing, Indigenous people, including the Métis, are disproportionately impacted. While Indigenous people represent only 5% of the Canadian population, in a 2022 point-in-time survey, 35% of homeless individuals identified as Indigenous.

The number of people living in motorized vehicles has increased dramatically along the south-west coast of Canada, where winters tend to be milder than in places to the east. As a result, communities from Squamish along the highway to Whistler, to Duncan on Vancouver Island, are struggling to accommodate the growing number of nomadic households. Most towns have very few mobile home parks, and places like Duncan (population 5,047) are finding their remaining RV parks once, used by tourists, are now hosting long-term residents who have nowhere else to go. Other less fortunate people are sheltering along roadways.

As an urban planner, I know people are always surprised, and sometimes disappointed, when I tell them that the hottest topic issue for residents is not climate change or housing affordability, but parking. Parking creates divisions between residents and business owners, drivers and non-drivers. Ultimately, almost every vehicle owner wants free or low-cost parking close to where they live, work, or play. Take away this option, and there is often anger and frustration. Permit parking “for residents only” is one way to try to appease people, but it ultimately privileges those who can afford to own or rent over those who can’t, leaving people living in vehicles with few options for where to park.

Examining parking from an equity lens could change how the land on the side of roads is allocated. Up to 30% of public land in any municipality is dedicated to traffic, approximately 1/4 of which is for parking. This may no longer make sense in the eyes of the next generations, with Millennials and Gen Z the least likely to buy a car. Coupled with this is the fact that currently one-third of the Canadian population is living in unaffordable housing, and could find themselves suddenly in need of a place to live. In this reality, prioritizing options for temporary housing may be more important than ensuring a smaller and smaller proportion of the population is offered a free or low-cost use of public land for their car.

In his ground-breaking study, The High Cost of Free Parking, Professor Donald Shoup does a deep dive into the costs related to parking, including the land that is paved over and the structures that are built. Shoup highlights that parking always comes with a cost, which is borne by someone, whether it is the government that builds the roads, the driver who pays the parking meter, or the tenant whose rent may include a parking spot. Free parking is, in fact, never free.

Shoup suggests ways to change our approach to parking that recognize the costs as well as the benefits. He recommends ensuring parking meter revenue goes back to the neighbourhoods from where it is collected. He also suggests eliminating parking requirements for new construction to lower housing costs, an approach which has been adopted by a number of Canadian cities such as Edmonton (2020), Toronto (2021), and Vancouver (2024), as well as regions across the United States.

I would like to take Shoup’s idea in a different direction. Street parking does not, in essence, belong to any one person but rather to the whole community, paid for through taxes. Parking on roadways is a public resource and could be allocated, in part, to those looking for space for longer-term shelter. No doubt this would take planning to ensure that parking spots are assigned equitably and strategically across any community. But the outcome could be that a portion of road systems would become a form of infrastructure for temporary housing and would provide a means to make precarious shelter somewhat less precarious.

Along a similar vein, the Town of Canmore, at the foothills of Alberta’s Rockies, created its “Safe Park Program,” which allows people who work in town and live in their vehicle to purchase a permit to stay. It is a seasonal program, presumably because winters in Canmore are too harsh for someone to live in a vehicle, or possibly because the demand for employees in town (not the ski hill) is only during the summer months. Either way, the town is making room for people who have been left out. The permit is $300 for May – September, which seems to be a reasonable rate for “free” parking.

Statistics Canada notes that in my hometown, Vancouver, BC, almost 41,000 residences (6.3% of all dwellings) offer inadequate housing. This means that people are living in residential units that have defective plumbing, poor electrical wiring, or require structural repairs to walls, floors, or ceilings. The majority of these are rental dwellings. This is on par with the national average (6.2%), and less than Toronto, which, at 8.5%, was significantly higher. In this dismal housing landscape, the option of a camper van on a side street makes sense.

A couple of years ago, I met Doug, a man in his 60s who was parked in an industrial area adjacent to a park. Doug had a slight build and was dressed smartly in casual pleated pants and a button-down top, like he was a visitor to the Eastside. His home was attached to the back of a truck, sitting on the flatbed and extended out over the cab of his truck. I was heading to the park next to his vehicle when he offered my dog a very large rawhide bone. He told me a friend of his with a dog had come to visit, but the friend’s dog didn’t like the bone and had left it behind.

He explained that the sleeping area was above the cab of his truck, a tiny space for him and his wife, who must have had an equally small build to his. He couldn’t keep the bone, he said, because there wasn’t room for anything extra in his vehicle. He and his wife, plus two birds, lived in the camper. I took rawhide, smiled, and thanked him. There was Doug, his wife, and their two birds all in less than 80 sq ft., giving away gifts to friends and strangers.

More recently, I spoke with Joanne, a woman who stopped to admire my dog. Joanne was tall with long dark hair and had been walking quickly, with the determined pace of someone who needed to get somewhere. But she stopped long enough to tell me that she had had a dog, and lived with him for a while in her new apartment before the dog passed away. Not far from us was some recently constructed social housing.

She told me it was hard to take care of her dog because he had been abused by her ex-partner and needed a lot of attention. She had lived in an RV for a while with her dog and cat until she got her apartment. She kept the RV, however, and parked it on one of the industrial side streets. Her ex-partner knew where she now lived, and despite a restraining order, came to her new building, threatening her. The RV was her escape, if needed.

One temporary housing collective found a more permanent location on Vancouver’s industrial Eastside close to my home. Approximately four RVs have been parked for more than a year on a dead-end street between two buildings and next to train tracks. One of the homes belonged to Andrea, who had a van patched together with cladding. Next to her vehicle, she had created a small garden in the boulevard and grew food in the summer.

Andrea stopped to talk with me one hot afternoon while I was gardening in front of my condo. She was thin and agile and felt like a powerhouse of energy. She told me she was an immigrant, had mental health issues, and had struggled with addiction. She was hoping to get back to Bolivia and set up a housing commune from what she had learned in Vancouver. I gave her my urban planning information—website and email—and offered to help. But I never heard from her. Another friend told me Andrea was no longer looking to leave Vancouver but needed money to build a safer, more structurally sound home.

Each of these people’s stories is different, each of their housing options complex, but they all carried a central them—needing a safe, reliable place in their community. They all found a housing solution that worked for them, given their limited options. They parked on flat roads and next to industrial land or parks, or tolerant buildings. These stories of human experience get lost in the bylaws, tickets, and towing that surround the urban nomadic lifestyle.

Across Canada, the number of people facing housing insecurity has grown and shifted from urban centres to smaller communities, as no place is unscathed from the housing crisis. Living in a vehicle is neither a romantic vision of modern nomads nor a problem of outsiders coming into communities. Rather, it is a creative solution to an unaffordable world, and a world with fewer and fewer safeguards.

Living in a vehicle is an alternative to paying up to 75% of income on rent, if there is an income. Living in a vehicle has many drawbacks, such as the insecurity of location, of neighbours, and of safety. However, these are issues that urban planners could address.

As a first step, cities and towns could explore how public right-of-ways can offer temporary, limited housing solutions for people living in their vehicles. For Vancouver, I imagine a system similar to Canmore’s, only year-round, where people can apply for a permit to park their vehicle on an annual basis. This alone may provide enough stability to ensure that some people without permanent housing connect to more stable options. One or two parking spaces could be offered in different locations, such as adjacent to parks that have washrooms.

In Vancouver, this would create approximately 70 stable parking spaces. Basic services could be delivered to the vehicle residents through existing park maintenance, such as garbage collection and washroom cleaning.

Parking permits for ongoing temporary vehicle housing are in no way proposed as an ‘easy’ solution. Like most North American cities, more affluent residents are more likely to complain than the less wealthy, and will often protest over anything that is perceived as a challenge to their privileged lifestyle. In Vancouver, initiatives have been stopped in their tracks due to complaints from wealthier neighbours, projects ranging from child care to social housing.

Temporary vehicle parking projects would have to be initiated carefully, but equitably, and monitored objectively, not just based on neighbours’ complaints.

If nothing else, secure temporary parking would be a starting point to acknowledge the needs of people living in their vehicles. Recently, a young woman was parking around my home, with her dog and bird in the car with her. I wanted to reach out, but I think she saw me as one of those neighbours who would complain and tended to avoid me. And I had nothing to offer her other than the acknowledgement that her situation was no doubt hard.

It is for her, and Yvonne, Doug, Joanne, Andrea, and all the others that I would like to see safety and stability for at least a little while. Offering public land for people living in vehicles embodies a form of acceptance and welcoming. It recognizes that someone living in their car has the same basic needs as everyone else. It could be a start to redressing the wrongs of the past, from the 19th century up to today.

***

Reddit Post-script (February 2025):

- Q – Middle-aged female here, I don’t feel safe at the shelters, so I live in my car. I have a free gym membership that I use to shower. I go to the library to use their wi-fi and warm up during the day. I have a small amount of money coming in, basically just enough to cover my insurance, fuel, and have a few dollars left over that I put in a bank account to save up to rent a room someday. I have no money for food, so I drive to places that give me free meals in the city I live in (Kingston).

The places have to have free parking because I can’t afford to pay for parking. I’m wondering if others here live in their car and want to share tips? I tried to find a subreddit for people who live in their car,s but couldn’t find any. There are ones for people who RV full-time, but that’s very different. - A: I hope you have applied for emergency housing based on your homeless status

- Q: I have. The wait for a single person is over 10 years.

***

Maria Stanborough is the principal for C+S Planning Group. 21st Century Road Allowances is part of a collection of essays focusing on urban planning, social justice, and Vancouver’s Eastside.

Amy Liebenberg is an urban planner and artist who divides her time above and below the surface of the ocean.