In 2023, the Vancouver City Council recently adopted a motion titled “Uplifting the Downtown Eastside and Building Inclusive Communities that Work for All Residents.” An update was released earlier this year, and the associated DTES Housing Implementation report created in response to public engagement is scheduled to be heard at Council on December 9th.

On the surface, the title offers a generous phrase—a soft, aspirational promise that gestures toward care, improvement, and collective betterment. Who, after all, could reasonably oppose a plan to uplift a neighbourhood long marked by poverty, trauma, and systemic neglect?

But the word deserves inspection.

Because in cities, words rarely remain poetic for long. They metastasize into bylaws, zoning schedules, development incentives, and redevelopment schemes. Over time, they turn into walls, leases, eviction notices, and displacement.

So, before we debate density numbers or unit mixes, it is worth pausing—not at the policy, but at the prose—and asking a more basic question: What does it mean to “uplift” a neighbourhood that has already endured decades of being managed, reimagined, and repeatedly “fixed” from above?

This piece offers a language audit—not to nitpick phrasing, but to examine how certain words quietly frame which futures are imaginable, whose presence is temporary, and whose is meant to last. I have explored political rhetoric and inequality in the past, and think it’s worthwhile to return to it here, with a different register and context.

Planning language has always carried double duties. Officially, it communicates policy. Unofficially, it trains people on how to feel about that policy.

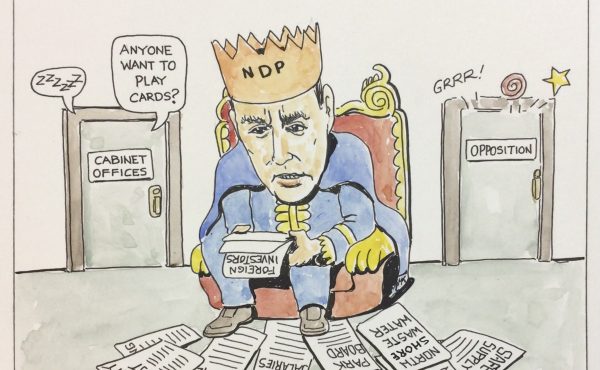

Terms like revitalization, renewal, transformation, and activation do not merely describe change—they moralize it. They recast disruption as progress, replacement as improvement, and resistance as backwardness. Over time, these words become so normalized that they no longer feel political, even though they do political work every day.

The Downtown Eastside plan is no exception. Its language is careful, measured, therapeutic even. But it is precisely this tone of care that demands critical attention. Because planning history shows us this uncomfortable pattern: the more benevolent the language, the more important it is to scrutinize the outcomes it makes possible. As I argued previously, planning’s language of ‘care’ and ‘protection’ often masks structural violence—and this DTES proposal appears to rehearse the same script.

Let’s look closely at a few of the core terms used in the City’s framing.

To uplift suggests elevation—a movement upward from something lower. In urban discourse, this often carries an implicit judgment: that the current state of the neighbourhood is something to be escaped, transcended, or corrected.

But uplift from where, and into what?

In the case of the Downtown Eastside, the term subtly frames the neighbourhood as a space defined primarily by deficiency: lacking opportunity, safety, or proper form.

This framing sets the stage for intervention. And crucially, it implies that improvement can only come through significant structural change—often physical redevelopment—rather than through stabilization, support, or reinvestment in existing social infrastructure.

Historically, uplift in urban planning has often arrived hand‑in‑hand with displacement.

From mid-20th-century urban renewal programs to more recent “regeneration” strategies, “uplift” tends to occur spatially—towers replacing walk-ups, mixed-use developments replacing low-income housing—and socially, through demographic turnover. The neighbourhood may become “better” by some metrics, but often not for the people who endured its hardest years.

Here, uplift risks functioning less as care and more as a justification for reconfiguration.

Few planning phrases are as ubiquitous—or as revealing—as revitalization.

To revitalize is, quite literally, to bring life back. But the Downtown Eastside is not lifeless. It is dense with people, memory, improvisation, care networks, and political struggle. Calling it in need of revitalization implies a lack of legitimate life in its current form—as though only certain kinds of vitality count, usually those that photograph well for consultants or align neatly with market value, commercial attractiveness, and visual order.

The sister phrase, “unlocking potential,” comes straight from the grammar of real estate economics. Land has “potential” when its exchange value can be increased.

In this framing, potential is not about human flourishing; it is about recalibrating land to meet what the market deems its highest and best use. The Downtown Eastside, then, is recast as an underperforming asset—a site waiting to be optimized rather than a community requiring protection, repair, and political restraint.

“Inclusion” sounds unimpeachable. But inclusion without specificity can conceal its opposite.

Inclusive of whom? On what terms? And for how long?

In many redevelopment narratives, inclusion refers to creating mixed-income or socially diverse neighbourhoods. On paper, this appears progressive. In practice, however, inclusion often operates through substitution: new populations are included not alongside existing residents, but in place of them.

Ironically, a neighbourhood can become more demographically “diverse” in census terms while becoming less accessible to those who historically shaped it.

When inclusion is not explicitly tied to tenure security, affordability definitions anchored to local incomes, and the right of existing residents to remain, it becomes a language of replacement rather than continuity.

These words are not floating metaphors. They harden into planning instruments.

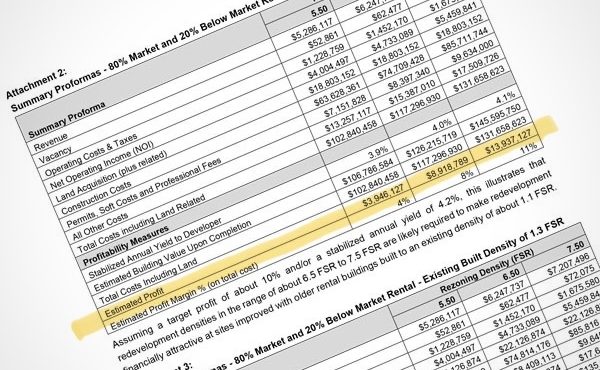

In the case of the Downtown Eastside, the language of uplift and inclusion is tied to concrete proposals: revised land use policies, changes to social housing requirements, shifts in how single-room occupancy (SRO) replacement is handled, and new permissions for market-oriented development.

The danger is not in any one of these individually, but in how they interact. When social housing targets are reduced while market development is expanded—all under the banner of uplift—the language does quiet work.

It reframes structural withdrawal as a form of intervention.

And when SRO protections are loosened while redevelopment potential increases, the language of care masks an emerging logic: that stability for low-income residents is secondary to transformation of the neighbourhood’s urban form.

In this way, the vocabulary of improvement quietly cultivates the conditions for displacement.

What makes the current moment particularly fraught is not just the scale of the proposed change, but the intimacy of the language used to justify it.

Planning documents now speak the language of care, wellness, and community. But care in policy is not about intention—it is about outcome.

If a plan claims to uplift, yet produces reduced access to shelter‑rate housing, destabilized SRO tenants, and greater precarity for current residents, its language of care curdles into a kind of moral camouflage.

The danger, then, is not only what the plan says, but how easily its sympathetic vocabulary anesthetizes public concern—dulling the political nerves just enough for displacement to proceed under a banner of benevolence.

If the words shaping our city matter—and they do—then we must ask what a different language would demand of us.

Here is one possible reframing.

When the City speaks of uplift, what is often occurring in practice is a process of replacement; a more honest vocabulary should name this instead as stabilization and support.

When plans promise revitalization, they often signal the pursuit of increased exchange value; a truer framing should be repair and reinvestment.

When policy documents refer to unlocking potential, they usually mean optimizing land for market performance; the alternative is to speak openly about protecting and sustaining existing communities.

And when redevelopment language calls for inclusive communities, it often masks demographic turnover; a more accurate commitment would be enabling resident continuity.

These alternatives do not promise glittering futures. They demand slower, harder, less photogenic work: maintenance, retention, long-term care, and political commitment to those who are already here. The Downtown Eastside does not lack life. It lacks secure housing, adequate health resources, and consistent public investment. But these are not problems solved by rhetorical uplift or aesthetic redevelopment.

If a neighbourhood is to be lifted, we must ask: lifted by whom? For whose benefit? And who decides when uplift has been achieved?

As I have argued elsewhere, when care becomes a form of control, these questions are not rhetorical—they are the only safeguards a community has against being managed out of its own future.

Until those questions are answered not just in language, but in guarantees of housing, tenure, and continuity, it is fair to ask whether what is being proposed is uplift at all—or simply yet another chapter in a long history of urban replacement disguised as care.

***

Other related articles:

- The Slow Emergency

- The Slow Emergency, Part II: The Emergency Escalates

- Trifecta of Control: Stealth. Speed. Compexity

- Entitled to Flip

- When Local Planning Becomes Provincial Command

- The Coriolis Effect, Part I: Planning by Spreadsheet

- The Coriolis Effect, Part II: Beyond the Spreadsheet

- The Coriolis Effect, Part III: Reclaiming the Planner’s Toolkit

- The Coriolis Effect, Part IV: When Viability Becomes Destiny

- When Care Becomes Control

- The Broadway Plan Blues

- Learning from Moses

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.