In recent years, Indigenous histories, place names, and knowledge systems have moved from the margins of urban development into its foreground. Land acknowledgements are now a standard feature of public meetings, Indigenous names appear in planning documents and design rationales, and the language of reconciliation, stewardship, and respect for place has become the standard professional currency. These shifts matter. They reflect a long-overdue recognition that cities are built on unceded Indigenous lands and shaped by Indigenous histories.

Yet, they also raise an unsettling question: Does recognition of Indigenous rights and the need for reconciliation, on their own, meaningfully change how cities are built? When recognition becomes routine, what work is it actually doing? Does it meaningfully change how development decisions are made—or does it risk becoming a way of making familiar development practices feel more ethical without actually transforming them?

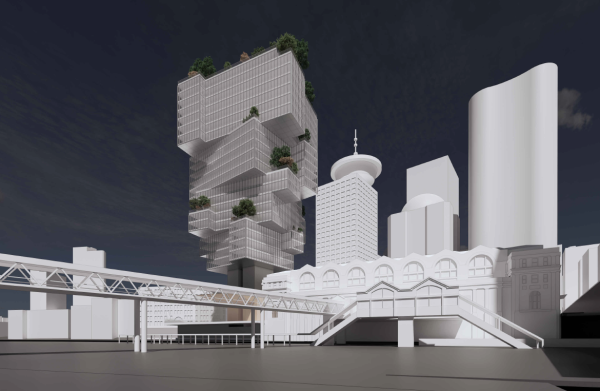

This tension becomes clear when Indigenous histories are invoked within otherwise conventional urbanism and architectural frameworks. Contemporary design rationales often rely on a familiar set of moves—lifting building mass to preserve views, shifting spaces to open the ground plane, breaking volumes into smaller components to respond to context, and incorporating green roofs or terraces for environmental benefit. Within these logics, Indigenous references are sometimes introduced as conceptual inspiration, such as the use of a local place name or a natural metaphor.

While these gestures signal some awareness and sensitivity, they rarely affect the underlying structure of the project. They do not alter ownership, governance, decision-making authority, or the economic logic driving development. Indigenous presence is acknowledged symbolically, while the project proceeds according to established planning and market norms.

In this way, Indigenous knowledge systems are frequently reduced to narrative or form-language—an overlay that adds cultural meaning without changing material outcomes.

This dynamic becomes especially clear when reading public-facing project documents alongside design imagery and technical data. The recently released redesign of 601 West Cordova is a clear case in point. Indigenous history is introduced as conceptual inspiration, while all-too-familiar performance drivers govern the project: view cone compliance, height limits, floor area targets, and massing strategies optimized to meet them within a market-driven development model.

The design rationale draws on the site’s pre-colonial name, K’emk’emeláy (“Grove of Maples”), and frames the building through the metaphor of a tree; however, the operational logic of the project remains firmly rooted in contemporary development narratives rather than Indigenous systems of governance and stewardship.

Metaphors such as the “tree,” for example, may organize massing or circulation diagrams, but they do not engage Indigenous land ethics, systems of stewardship, or understandings of land as relational rather than extractive. The design remains legible, defensible, and compliant, yet its engagement with Indigenous histories does little to challenge the colonial foundations on which urban development continues to rest.

Renderings further reinforce this separation: the project is presented through distant skyline views and carefully framed images of an open plaza and lobby, visually establishing publicness and civic contribution without addressing how these spaces will be governed, programmed, or contested over time. Public space is rendered as atmosphere and access, rather than as a question of authority and responsibility.

But this is not merely a matter of architectural storytelling. The same logic appears at the level of housing policy.

A 2021 letter from the Urban Development Institute to the Province of British Columbia, framed as a pragmatic discussion of affordable housing solutions, offers a revealing example. In its section on partnerships with First Nations, the letter describes Indigenous Nations as poised to become major developers, emphasizing their ability to deliver large projects, establish benchmarks for density, and move more quickly than municipalities that might otherwise slow or reduce project size through servicing agreements.

The letter notes that First Nations are expected to become “the largest developers in the Province” and explicitly encourages governments to ensure that local authorities “do not slow down or reduce the size of the projects,” framing Indigenous participation as a way to overcome regulatory friction rather than to reimagine development itself.

Reconciliation is explicitly celebrated, but it is immediately translated into development capacity, speed, and alignment with provincial housing targets.

Notably absent from this framing is any discussion of Indigenous governance, land ethics, or authority to redefine development itself. Indigenous Nations are encouraged to participate more fully in the existing system, including through training to address labour shortages and becoming developers in their own right.

This participation is also entirely understandable: after generations of dispossession and exclusion from land wealth, many Nations are pursuing development not as a sign of assimilation, but as a pragmatic strategy to generate revenue, deliver housing, and strengthen sovereignty in a system that has long denied them economic control.

However, while inclusion is presented as empowerment in the letter, it also implies assimilation: the system remains unchanged, and success is measured by how effectively Indigenous actors can operate within it. There is little space for Indigenous knowledge to question the pace, scale, or purpose of development, or to assert limits based on stewardship, responsibility, or refusal.

Read together, these design and policy examples reveal a broader pattern: Indigenous presence is increasingly recognized, but that recognition is carefully contained.

It is allowed to inspire, decorate, and legitimize, but not to redistribute power or disrupt dominant development logics. This can be understood as recognition without transformation—acknowledgement without a corresponding shift in land control, decision-making authority, or economic structure. In this context, Indigenous knowledges become a stabilizing force, helping colonial development systems appear more just and inclusive while continuing largely unchanged.

In essence, ethical language functions as moral cover.

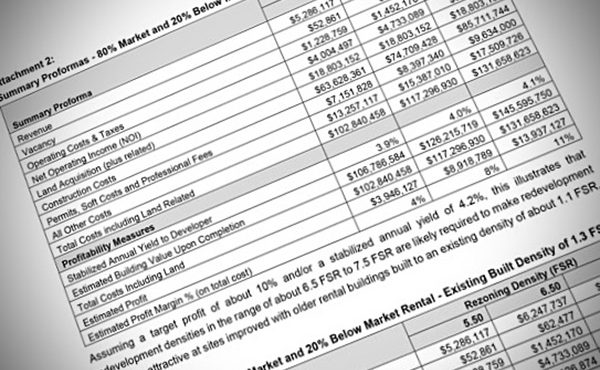

We’ve seen this many times: Indigenous names on public plazas that are privately managed, cedar motifs in lobbies that remain inaccessible, and reconciliation language in project descriptions that never appear in pro formas. The discomfort that should accompany development on Indigenous stolen lands is softened by symbolic gestures, allowing projects to move forward with greater legitimacy and less resistance.

Reconciliation, in this form, becomes something that smooths standard development rather than something that challenges it.

The issue, then, is not whether Indigenous histories or knowledges should be referenced in architecture and planning—they should. The more challenging question is what those references are permitted to do. What would urban development look like if Indigenous presence carried the power to delay, reshape, or refuse projects, rather than inspire them?

Until recognition is paired with transformation, the invocation of Indigenous knowledges risks becoming not a step toward justice, but a new language through which colonial development secures its legitimacy and continues uninterrupted.

***

Related Spacing Vancouver pieces:

- The (Ur)banality of Evil

- The Coriolis Effect (3-part series)

- The Pro Forma Problem

- Defining “Viability”…and Who Decides What Counts?

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.