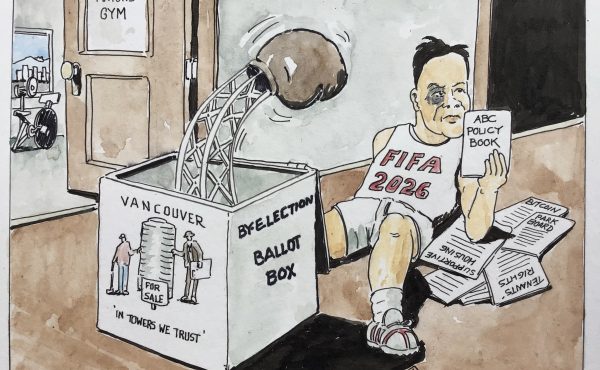

[If you’re reading this before 8pm, polls are open. Still lost or caught by surprise? Check out Spacing Vancouver’s recommendation post for more information on how to vote and who to take a closer look at.]

The first post of this series went some way to explaining Vancouver’s relatively unique electoral system, but before the ballots start going into the box it’s useful to go into a little more depth as to how it works – and doesn’t work. To begin with, each voter will be presented with a list of 94 candidates across races for the mayoralty, council, parks board, and school board. Without a ward system, every Vancouverite gets one vote for mayor, ten for council, seven for parks board, and nine for school board, for a grand total of 27 votes.

Counting votes is rather straight-forward – simply add up the totals and take the top ten, seven, or nine. This is first-past-the-post on a grand scale, with the potential for candidates to squeak through on a plurality twenty-seven times over. To make things simpler yet, most candidates in contention come branded with a particular electoral organization‘s stamp of approval. In English, Vancouver has entrenched party politics. It also, again relatively unusually, allows non-resident property owners to vote in its elections.

The vote in 2008 went 55% Robertson (Vision), 40% Ladner (NPA) – but voters lost interest down-ballot, casting only 8.4 of their 10 council votes. All council candidates polled behind their mayoral candidate with the exception of Suzanne Anton at the equivalent of 43% (a remarkably rare result: one has to go back to 1996 to find Tim Louis doing better than his COPE mayoral candidate, but they both lost to an NPA sweep). Elected Vision candidates ranged from 54% (Louie) to 40% (Meggs), with Dhaliwal missing the mark at 36%. COPE’s Cadman and Woodsworth came in at 46% and 37% respectively. The nine NPA candidates who couldn’t clear the bar ranged between Geller (36%) and Sidhu (23%).

While the lower vote counts could be chalked up to voter apathy, incomplete ballots – combined with split tickets – are the only thing preventing even a one percent difference in the mayor’s race from turning into ten council seats as well. As it was,Vision/COPE took 46% of the possible council votes and elected 9 councilors, while NPA took 32% and elected 1. A more proportional result would have looked something like 4-5 Vision, 2.5-3 NPA, 2-3.5 COPE (as opposed to 7-1-2), but it is difficult to untangle the Vision/COPE split ticket and other factors. From 2008, check out the results for 2005, 2002, 1999, and 1996 before waiting to see how 2011 makes a landslide out of a few pebbles’ difference.

This system, adopted in 1935, has understandably aided the rise of party politics in Vancouver. Indeed, as Frances Bula explores, the NPA was almost a direct result of this change, born in 1937 to oppose the CCF (proto-NDP) from the right. Its original platform, chronicled in a UBC thesis, claimed “to oppose the introduction of party politics into the Vancouver’s city administration.” If they were measurably successful in this goal, it could only be through their sheer dominance, with their council majority unchallenged for their first 27 years and 25 of the next 44. The NPA’s opposition varied from their left to right, and would generally be best described as electorally ineffective. The challenge of building a bigger, yet stable tent has proven difficult to meet.

The historical record suggests that the original ward politics in Vancouver were doomed on two major counts. Firstly, the amalgamation of Vancouver with South Vancouver and Point Grey in 1928 led to an odd system of boundaries with wards primarily running in thin north-south strips, widening in the east to the point that a typical East Vancouver ward had three to four times the population of the Downtown ward and up to double that of those to the west. Secondly, the 1933 provincial election was a realignment with typical conservative voters throwing their lot in with the Liberal party to fend off the CCF – a movement that extended to municipal politics. Overwhelming support across the city in the electoral referendum was then not unexpected, nor was the referendum itself.

NPA Mayoralty Vote in 1937 and 1940

Whether the institutionalization of party politics was the fault of the CCF for introducing them or the NPA for perpetuating them, the damage was done. Without wards, block voting helped entrench an existing ideological divide that arguably exists today. The overwhelming east/west split coming out of the Great Depression has transitioned into today’s rough northeast/southwest split, with the West End/Downtown and Kitsilano trading places with neighbourhoods like Fraserview. While first past the post favours a two party system, block voting has nearly created a one party system with periodic opposition from TEAM and COPE from the 1960s on.

NPA Mayoralty Vote in 2002, 2005, and 2008

While a return to a ward system would be one possible reform, it’s unclear whether it alone would promote more diversity. Smaller campaigns would be easier to mount, but surely the existing parties would continue to run city-wide campaigns, pooling resources and attention, for the immediate future. COPE strongly favours a ward system, but the cynical analysis would be that they recognize they are better bunkering down in friendly territory than scrapping over the city as a whole. With relatively entrenched ideological boundaries, a ward system could simply lead to a realignment in which a few swing wards control the balance of power.

Wards are hardly the only option. A ten person multi-member constituency (i.e. council) is almost exactly the kind of thing BC STV had in mind – and when compared to the existing system, it’s hard to make any of the arguments that sunk it provincially beyond simply being complicated in its attempts to be as fair as possible. Even a move to a simple ranked choice/instant run-off system (especially for the mayoralty) would make a world of difference, however, in taking away the peer pressure against “throwing your vote away” on the principled underdog. San Francisco and Oakland, for example, already do this, as do many internal party votes even when the party line opposes the system for the unwashed masses.

The question seems, for now, to be relatively moot. Regardless of who gets elected, it’s unlikely that there will be enough votes for any kind of reform. Whether Vancouver has a one-, two-, or two-and-a-half-party system, there simply isn’t anyone who stands to benefit from a new model once in power, and that is exactly how first-past-the-post and block voting perpetuate themselves.

***

Spacing Vancouver will continue to bring you periodic updates as the race progresses – you can find the complete list here.